Nonfiction

No Aguanto

Giving Voice to Our Pain

by Leticia Urieta

There is a word in Spanish that comes back to me: aguantar. Strictly translated into English, it means to endure despite the weight of a negative force, but its usage can move across contexts. The one that I have heard most often—and from a woman’s mouth—is the kind of pain, worry, or sorrow that she is able to endure, and at what point her limits have been surpassed. As in “no puedo aguantar más.” I cannot endure any more.

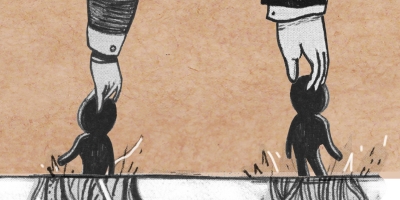

I learned this word from my paternal grandmother’s mouth, in tears and in silence, as she endured and then no longer could. Endured living with my verbally abusive father, as she had lived with my abusive grandfather before him. Endured the weight of generational familial abuse on the rest of the family. She let toxic machismo endure even as it was killing her.

Grandma’s endurance was desperate silence, a cool demeanor. She was consistently abused, manipulated, and mistreated for much of her adult life. When her cheating husband was confronted by the husband of his lover as their family sat eating at a restaurant, Grandma calmly took the man aside, put her hand on his arm, and asked him not to beat her husband in public in front of her children. The money she earned cleaning houses for rich white families was often given away to her family, who took advantage of her feelings of familial obligation. Until the stroke that unleashed an outspoken woman, my reserved grandma applied her makeup and curled her hair every day, even when she could barely lift her hands above her head, even when it became difficult to live from month to month after my father took a good portion of her Social Security check.

In the nursing home, I’d hear a scream so violent it rattled Grandma’s throat. It erupted whenever the nurses moved her from chair to bed, or had to change her clothes or give her a bath. She cursed them, and she cursed me and my cousins. She was louder at the end of her life than I had ever known her, leaping across English and Spanish to find the best words she knew for her pain, calling us malcriadas and bitches. On one particularly bad day, she insisted that someone was sawing off her leg, even though it sat perfectly still in her chair. From her bed, she pleaded with me in tears to make the nurses stop trying to move her. She seemed unconcerned that she had lifted her nightgown above her thigh to show me her still leg, insisting I look. “Mira, mijita, mira lo que me están haciendo,” she told me, shaking her nightgown and willing me to see what was not there. Even when she calmed a few minutes later, her more placid tone was tempered by the accusation in her cloudy brown eyes.

I cried in the car on the way home. But I was glad, for once, to see this woman who had helped raise me finally be loud and unruly, when propriety had kept her quiet for so long.

In her book The Body is Not An Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love, poet and author Sonya Renee Taylor asks the reader to engage in “radical reflections” about their relationships to their bodies and the bodies of others. When I began reading this book, I found myself responding to some of these prompts in the form of short journal entries. The one reflection that prompted the most writing from me was “In what ways have you been asked to apologize for your body?”

This was a question I had considered in other contexts, when I had been made to apologize for my weight, for how much room my body took up in a space, or for wearing clothing that was “too revealing” because of the way my curves spilled out—even in clothing that would otherwise be considered modest. But this question of apology resonated with me more than ever as I was recovering from a sinus surgery. I’d had the surgery because I’d hoped it would alleviate two years of chronic migraines, nosebleeds, and pain that had disrupted my life. As an adjunct professor with no contract, I had had to cancel classes—and risk future employment—because I could not leave my bed without becoming faint or vomiting. These moments wrenched control over my body from me and left me feeling childlike, helpless to do anything to alleviate my suffering.

I am often told by doctors, specialists, dentists, and technicians that I am such a good patient because I don’t flinch, scream, or flail when I am pierced by a needle or when my nerves are drilled into and pain sensors flair and the blood comes after. The sad thing is I have always prided myself on being labeled a “good patient.” I have done my best not to inconvenience the professionals who, I have always been taught, are the bastions of all medical truth.

During my sinus surgery, I woke up a few times under sedation. I have distinct bodily memories of the sharp, cold metal instruments working inside my nasal and sinus cavities, of the sound of my own moans for the surgeon to stop. Then darkness, and eventually waking and sobbing, as though the surgery had been a particularly intense dream I had slipped out of, back into the waking world. My rational brain could not comprehend why I was crying, and I silently scolded myself. It wasn’t until I realized how much blood was pouring from my nose and the intense, face-shocking pain hit me, that I realized how much of the surgery I had felt, and how much more I was destined to feel. The anesthesiologist said, “I’m sorry that you woke up,” but it sounded less like an apology and more like an accusation of my body’s inability to surrender to the hands of doctors who, in the process of trying to fix me, had harmed me.

All too often, our pain is an inconvenience for those who have to treat us and care for our ailments.

Throughout this long treatment process, I thought of the stories my friends and family with chronic illnesses had told me. Of the ways in which they had been dismissed when their bodies did not respond to a linear treatment plan or expected outcome. A friend with type 1 diabetes once recounted her quest to lose weight and lower her A1C levels, which was seemingly endless even though she altered her diet and exercise habits. Her doctor consistently shamed her for the lack of change, repeatedly asking, “What are we going to do about this?” In a last-ditch effort to affect these levels, her doctor prescribed her a medication that would supposedly help, though its primary side effects are nausea and diarrhea. As my fatigued friend told the story, she threw her hands up, frustrated that her trusted endocrinologist had prescribed a glorified laxative because her condition was more her fault than his.

As I navigated the saga of my own pain, I found myself drawn to the stories of other women whose pain had been dismissed by the medical community, and whose voices were declaring this pain as part of themselves despite the attempts to silence them. In her latest collection of poetry and essays, Night-Blooming Jasmin(n)e, Jasminne Méndez chronicles her experiences and struggles as an Afro-Latina woman with pericardial effusion and pericarditis that have affected her throughout her adult life. In one essay, she responds to a nurse who attempts to dismiss her concerns:

I lifted my shirt and pants and was hooked up to an EKG machine because I was once again in the ER complaining of chest pains and shortness of breath. The nurses asked for my health insurance card, and there began the usual flurry of activity I had come to expect in these cases of emergency.

Velcro ripped on the blood pressure machine, vitals checked, machines beeped, the paper curtain rustled open and closed behind me. I stood on the scale, answered inane questions and explained why the pulse oximeter said I was not breathing.

“I have Raynaud’s. You’re not going to get an accurate reading from my fingers.” The young white female nurse in baby blue scrubs looked at me and said, “You’re too pretty to be this sick.”

I stared at the retro tiled floor annoyed by her comment. “Thank you, but clearly lupus doesn’t care how pretty I am.”

Méndez’s words are more than an account of pain made invisible by youth, beauty, and perceived “normalcy.” They are a declaration in the face of this pain when no one wants to hear it. Considering the way that women of the African diaspora have historically had their pain dismissed by the medical community, this honest witnessing of her own pain is necessary. This passage reminds me of times when my youth or perceived health caused doctors or nurses to dismiss the severity of my pain. For a period in my late twenties, I was told that an irregular swooping feeling in my chest, close to my heart, was just a symptom of anxiety that doctors often see in “women your age,” even when I iterated that this felt different than a panic attack. After several EKGs and chest scans, I still don’t know why this happens to me. I struggled to insist on my pain or discomfort, or on my needs, as Méndez did, but I am reminded of how necessary it is to speak our truths, even when these gatekeepers of health don’t want to hear it.

In her book, Taylor explains how living in our bodies often disrupts the default understanding of what a body should be, including the assumption that it should be healthy and free from pain. Before my sinus surgery, health had always been something I thought of as an achievement, something to strive for because without this effort, what was the alternative? As I heard the voices of the women who have been struggling longer than me, and who had to be their own advocates in a system that wanted their silent conformity, it became clear just how much I had relinquished control over how my body had been treated in the past.

At twenty-four, I experienced my first UTI. I was a kindergarten teacher entering my third year of teaching, and on the day before school would start, I was busy at work readying my materials and classroom for my incoming students. Because I had never had an infection like it before, I waited until the pain was so bad that I rushed from my unfinished classroom to the bathroom at least four times and urinated blood. Later, at the hospital with my husband, I quietly snuck off to the restroom every three minutes. Urinating felt like passing particles of glass through my urethra, and each time I went, I felt that something irreversible was happening to me.

My husband and I waited four hours before I was finally able to see a nurse. Despite the excruciating discomfort written on my face, the extent of my infection was not taken seriously until I handed the nurse a sample of my urine that was black with blood. Taking it from my hand, she muttered, “Oh my God,” and I was rushed into a room to receive antibiotics. Later, an ER doctor told me that the infection had caused my bladder to hemorrhage, and that it was close to infecting my kidneys. After this experience, I went to the restroom more regularly and took cranberry pills, but more than anything, I took with me the sense that remaining “brave” in the face of my own pain might kill me.

I understand that it is difficult for medical professionals to truly understand their patients’ pain when they’re not experiencing the pain themselves. It is a struggle that continues without radical acts of empathy from medical professionals and other caretakers. This problem continues when doctors and specialists treat ailments as individual issues, rather than looking at a patient’s health holistically. What happens when pain or illness is not evident? To what extent must illness be proven?

I was recently told by a particularly good massage therapist that she felt a lump in my left thigh. She had been working the muscles in my legs for fifteen minutes before she informed me in a calm voice, so as not to startle me and ruin the rest of the session. When I went to my general practitioner, he spent less than five minutes feeling the lump through my jeans before pronouncing it “most likely benign.” My mortal fear was such an inconvenience to his busy schedule that he could not even be bothered to examine the lump further before stating his approximate diagnosis. He recommended that I get an ultrasound of the lump, just to be sure.

During the procedure, I lay bare-bottomed on the chair while the tech poured gel on my thigh and complained that the lump was difficult to discern from the muscle surrounding it. The tech then left me in this vulnerable state, noting that the doctor, whom I had never met, could enter the room with me like this at any time to consult the image. I was told to just sit tight. And I did so, without complaint. Though the lump was confirmed to be benign, the experience was yet another reminder that my well-being and comfort were secondary to the procedures of the radiologists who cared for me.

There are too many stories of women insisting on their need for treatment, only to be dismissed and sent home. Some of them die because they are misdiagnosed or wrongfully labelled “anxious” and “hysterical.” Some of them return and insist on saving their own lives. Many of these dismissals are rooted in a long history of patriarchal attempts to control women’s bodies and therefore our understanding of our own bodies. We are not often taught to be our own advocates until we are given no other choice. It bleeds into the ways we endure across all areas of our lives—how we are willing to endure toxic workplaces, abusive relationships, and unhappiness in many forms, but are quick to tell other women that they don’t deserve this kind of suffering.

I have only now begun to contend with the ways I have failed to be my own advocate. Despite advocating for the voices of others, I have abdicated my responsibility to care for myself to the expertise of those who would treat and label my body as they saw fit. Each time I suppressed my bodily instincts to shout, rebel, or run, my body learned that it was separate from my consciousness, and no longer free. How could I have compassion for others, but none for myself?

I continue to be inspired by women who refuse to suppress their pain for the sake of others’ comfort. While writing this essay, I questioned whether I even had a right to recount my own struggles. Did my pain qualify? The more I read and the more I listened, I began to understand that I was situating myself in a conversation that I hope will not soon end.

When writer and cultural critic Roxane Gay curated and contributed to a series of essays called Unruly Bodies at Medium, I read these pieces every week, feeling particularly seen with each one. One such essay, by Carmen Maria Machado, “Unruly, Adjective,” speaks to her daily existence in her body, listing her pains, her ailments, and the many parts of her that make up a body which will not fall in line. Her essay ends with this glorious statement:

I do not hate my body, because such a thing would be pointless, shortsighted. You cannot hate an animal for what she is, especially one who bears your ungrateful mind through this terrible world. And anyway, how do you hate something who marks her territory so dramatically, with such violence and panache? Who reminds you, with each step, I am here, I am here, I am here?

The way that Machado illustrates the power of her body in its free expression of imperfection and pain is beautiful, and haunting. While reading, I thought of a question in the last chapter of Taylor’s book that I am still asking myself: “If you decide to be at war with your body, how will you ever have peace?”

After my sinus surgery, I had to get three fillings at the insistence of my dentist. Throughout the procedure, the dentist and dental hygienist seemed to be in a tug-of-war with my mouth, until my cheeks stretched so far out I wondered if they would ever return to their original shape. I clenched my fists and sighed to express the intensity of the pain inflicted by the inch-long needle sinking into my gums. The hygienist patted my arm and told me to breathe through my nose, which, because of the previous surgery, was congested beyond breath. In her Northern Mexican accent, she told me, “It’s okay, mamá” every time I struggled, coughed, or flinched, and each time she did I felt less comforted and more betrayed. She was asking me to stifle my pain because when I gurgled and flinched, she had to look away.

I wonder what my grandma would say to this woman who attempted to calm me in the language of my familia, as if she were my ally. I imagine her raising her weak hand with its yellowing, clawlike nails and slapping the woman across the face.

No, no más. I will not endure.