Nonfiction

God or the Devil or Me

by Amanda Miska

Destiny is a worrying concept. I don’t want to be fated. I want to choose.

—Jeanette Winterson, Written on the Body

Let’s play Would You Rather.

Would you rather have a spectacular love that eventually crashes and burns or a mediocre love that lasts forever? The ability to fly or the ability to breathe underwater? Shit that tastes like ice cream or ice cream that tastes like shit? Meet your soulmate or the best fuck you’ll ever have? Heaven with all the people you hate or hell with all the people you love?

Would You Rather is a game, but also not. Life itself is a would-you-rather reality with real consequences: you have to choose and then wonder forever if the choice you made was right.

Or maybe that’s just the definition of anxiety, from which I suffer, and which runs parallel to my depression. Mental illness passed down, a one-two punch from each side of my family. I would rather have neither, or even just one of the two. But I wasn’t given a choice.

When they were in their thirties, my parents found evangelicalism. They turned to it as a way to heal their broken marriage and find community after starting over in a new town. At thirteen, I had no autonomy and went to church as well. The tiny, independent fundamentalist Baptist service took place in a small old firehouse the church rented, outfitted with a movable pulpit, a piano, metal folding chairs, and a linoleum floor in a shade of beige that made it look perpetually dirty. Surrounding the firehouse was a gravel driveway that led to a gravel parking lot. It sat in the middle of a small village just outside of the larger town where we lived, isolating it even further from the influence of the contemporary world.

Growing up, we had attended Catholic masses. I had been baptized as a baby, taken communion and been confirmed in elementary school. I had a more than healthy fear of hell that would sometimes manifest itself at night: What if I didn’t make it to confession after a sin and then I suddenly died? What if my parents, who almost never went to confession, died? I would wake up in a cold sweat and sometimes wake my parents, too.

When I got bored in mass, the interior of the beautiful Roman Catholic sanctuary kept me distracted. I loved the sickly sweet smell of incense, and the somber drone of the organ made the place feel mysterious, so different from the pop and country music that played incessantly from our boom boxes and car stereos. The towering stained-glass windows alone could keep my mind busy—images of the events of the Crucifixion in bright primary colors, Jesus hanging on the cross, face in agony, his hips draped in only a piece of white cloth.

But there was nothing of beauty in this main hall of the Baptist firehouse. Drab everything. Even the people looked like they had stagnated in the early 1980s, with their feathered hair and unflattering, modest clothing in neutral shades. At the end of the first sermon of the first service I begrudgingly attended with my parents, the pastor told us to bow our heads and close our eyes. “If anyone would like to know for sure if they are going to heaven, would you raise your hand?” And I did. I wanted to know for sure.

After the service, the pastor and co-pastor and my parents and sister and I went back into the tiny foyer of the church, and I got saved. I bowed my head and parroted each line of a prayer the pastor gave me, commonly known as the Sinner’s Prayer: Dear Lord Jesus, I know that I am a sinner, and I ask for Your forgiveness. I believe You died for my sins and rose from the dead. I turn from my sins and invite You to come into my heart and life. I want to trust and follow You as my Lord and Savior. In Your name, amen. My sister did the same thing. My parents were emotional after the amen, and that made me feel emotional. There was a sense of relief, too, like a long-held breath expelled.

I was twelve, almost thirteen. We had just moved away from our small hometown in western Pennsylvania, where I’d grown up with both sides of my family, cousins who acted more like siblings, and a tight-knit group of friends with whom I still wrote letters back and forth. After I was saved, I wrote a different set of letters. After a week away at a fundamentalist Baptist church camp, I did what I was taught to do as an evangelical Christian: evangelize. I shared my faith and explained how my friends, too, could get saved. A new fear replaced my old one: I was now afraid that everyone I had ever loved, save for my immediate family, was going to hell. I got some letters back here and there. No one mentioned my faith, and eventually the letters dwindled and then stopped. I made friends at church and school and left my old life behind.

There is comfort in the idea of predetermination. The idea that no matter what choice you make, the outcome is ultimately the same. For someone with anxiety, this is very appealing. I quickly learned that when the church said faith, what they meant was certainty. Sure, maybe some of the details were hazy, but at the heart, the church had the answers. The church knew the way. And everyone else be (literally) damned unless they came to those same conclusions. I wanted to be right. I wanted to know, without a doubt.

My parents eventually moved to a slightly less fundamentalist Baptist church. A new youth pastor and his family joined, and they were attractive and fun and charismatic and kind. I went to church every Sunday, and Sunday school, and youth group, first as a student and then as a leader. I committed to saving myself for marriage. I studied the Bible. I went to retreats. I sang in the worship band. I prayed daily. Sometimes I lifted my arms during praise songs, moved by the spirit. Sometimes my eyes would fill with tears or I would get a lump in my throat during worship, especially if it was a song about Jesus dying for my sins.

When I was seventeen, I developed severe subcutaneous acne on my face. The very first blemish was so deep and painful, it felt and looked like a bruise on the inner corner of my eyebrow. It was as if someone were pressing on it incessantly from the inside, a pain I could not ignore. From that point on, depending on hormones or stress, I would develop anywhere from two to ten of these sores on my forehead, nose, or chin. I would pick at the breakouts, leaning in close to the mirror, squeezing or scraping, sometimes with my nails, sometimes with tweezers or a sewing needle. Deep shame and depression kept me from wanting to leave the house to go to school or church or youth group or anywhere. Sometimes I would be completely immobilized behind the closed bathroom door, unable to breathe. Sometimes I would pick so badly no cover-up could hide the damage.

In those days, when I looked in the mirror, I often told myself aloud that I was disgusting and stupid. Sometimes I would dig my nails into my skin even deeper, just to hurt myself more. If I was able to go out, satisfied that my wounds were hidden well enough, I had to have some kind of concealer with me at all times, or I would panic.

Around this same time, internet speeds started picking up, and I stumbled on porn for the first time. I had seen a VHS video at a friend’s house in ninth grade, but there was nothing like that in my house. The closest thing I’d ever had to porn were my grandma’s romance novels, which I’d paged through when I was way too young, skimming for the juicy parts. Our computer was in the basement, which added an extra level of seediness. I found the porn clip itself disgusting—just missionary thrusting on a bed. The man was too tan and muscled; the woman had on theatrical levels of makeup, and her hairless vagina confused me. But it was the sounds they made—the voyeuristic quality of me listening in—that turned me on.

After that, I began to occasionally seek out arousal. But I knew I could never tell anyone because if it was bad for boys to do it—pornography addiction was a huge topic for every men’s group at our church—it was doubly shameful for a girl. We never even talked about porn or masturbation in our single-gender purity/sexuality study—only how to dress modestly so as not to tempt boys, and how far was “too far,” physically. I assumed that I was weird and perverted for wanting to touch myself, for being so interested in sex and sexuality. But I couldn’t stop.

I told myself I was afflicted with acne because of my porn “habit.” I would go weeks without masturbating or looking at porn or fooling around with my high-school boyfriend, and then, when I broke my promise, compare the impurity of my skin with the impurity of my life.

But nothing really helped my skin—not salicylic acid, not benzoyl peroxide, not tretinoin, not birth control, not the natural remedies my boyfriend’s herbalist mother prepared for me—and I couldn’t stop masturbating regularly, so I simply tried to live with the shame and pray for forgiveness. After I came, my stomach would churn, and I’d often cry. Pleasure and shame became inextricably linked in my mind.

In college, I lived at home with my parents because I was too poor to live in the dorms (and almost too poor to attend college at all). This kept me involved with the church and also kept me from evolving into a normal twentysomething with her own identity. I didn’t drink until my twenty-first birthday, and even then, it was a glass of wine with homemade pizza at the family dinner table. I never stepped foot into a fraternity or sorority house. Even though I went to a Big Ten school, I rarely went to football games. I didn’t play any sports or belong to any clubs. I never lived in a dorm. I experienced very little of the college life except for classes. I went to school and work and church. I was full of unsown oats. And even though I allowed the church to insist this restraint made me a good person, something inside of me always felt uneasy.

I want to die. This thought crept in for the first time during my junior year of college. It occurred after a particularly terrible skin lesion surfaced, one that couldn’t be fully hidden with makeup. Almost the size of a nickel, the lesion oozed with oil and was partially darkened with a scab. No matter how much foundation or concealer or powder I put on and then washed off—making it even more inflamed—I could not hide it. I was exposed. I was ashamed.

I didn’t make a plan. I didn’t think I could kill myself. I just wanted to sleep and not wake up. Or sleep and wake up with a different face, a different life. Sometimes, when crossing the street to class or driving home late at night, I would gently wish for an accident.

I knew I needed to talk to someone. Nobody knew how bad it was. How many classes I had skipped, how many times I had called in sick to work. To the outside, my immobility seemed like laziness, like a capable young woman squandering her potential.

I eventually went to see our church’s counselor. She was a woman whose children I had babysat when I was younger, and we’d known each other for years. I didn’t tell my parents I’d had thoughts about dying, so I didn’t tell her either. I talked about my skin, about picking, about being afraid and ashamed to leave the house.

She gave me a sheet of paper titled Who I Am in Christ. Below the heading, a pyramid of Bible verses were pulled out of context, all beginning with the words I am. I was to think of them like mantras. I am loved. I am a child of God. I am a temple. I am chosen.

The counselor also told me that when the urge came to pick—this voice, the devil—I was supposed to say aloud to the mirror: “Stop picking on me.” It felt stupid and silly, but at that point, I was willing to try anything if it meant I could be healed.

The word heal comes from the same etymological root as health and holy: the Proto-Germanic word for whole. In a world where I often felt fractured, that was all I wanted. I believed my body and spirit were connected. If I could just get one under control, the other would somehow follow. If I could be clean inside, then I could be clean outside. Healthy. Holy.

A group of prominent women in our church went to what was known as a spiritual-warfare conference, and returned to form what they innocuously called a prayer team, to deal with more persistent sins. By the end of my senior year of college, I was engaged to my high-school boyfriend, and we planned to get married two months after my graduation. While we had fooled around in our six years of dating, we hadn’t had sex. I wanted to be pure. I thought it would make me a better wife. I was told it would make for a better marriage and an even hotter sex life. I finally confessed to someone about the masturbation and porn, a trusted mentor, who suggested I go see the prayer team. Sexual sin, my mentor told me, was generational—it was also something that had plagued my father—and pornography was an addiction.

My “addiction” consisted of watching an internet porn clip for less than five minutes a few times a month. Maybe. And rarely thinking of it otherwise. Porn can be an ethically murky area; mainstream heterosexual porn—the kind most readily available at that time—usually isn’t feminist, and it portrays unreasonable standards for women’s bodies and the things they do. Of course I didn’t know that then. Was it the best sex ed for me? No. But because I didn’t have any real sexual experiences, it’s part of how I learned—not just the particulars of what might turn me on, but the basics. I had no other reference beyond the sterility of health-class lectures and the vague comments of slightly more experienced friends.

I wasn’t addicted to porn, but I thought I was because I watched it more than once, and no one disagreed.

I had been told this was sin, and I felt the shame deeply each time, which would feed into my anxiety and depression, which would make me crave release, which would lead back to either my skin-picking compulsion or masturbation or both—literally a sick cycle. I wanted to be healed.

So I made an appointment with the prayer team. The head of the team warned that I might get scared or exceedingly anxious in the days leading up to my meeting, that the devil would try to prevent me from going.

At the time, I had just moved into what would soon be my married home. True to evangelical form, my fiancé would not be moving in with me until he was my husband. It was the first time I had ever lived by myself. At night, alone in my new house, I heard noises. The creaking of stairs though they were carpeted, a light tap on the window. I hallucinated what I thought were demons near the foot of my bed, murky red and human-shaped. I slept—or attempted to sleep—with the lights on. I prayed, over and over, that I could be released from the fear and fall asleep.

Years earlier, at a local carnival, I had won one of those framed posters popular in the eighties. On it was a honey-colored kitten and a prayer that read: Dear Lord, I know that nothing will happen to me today that you and I together can’t handle. I’d said that prayer as a child when I got the nighttime scaries, and I said it again now. My heart pounded and I was drenched in sweat, but I was also afraid to kick off the blankets that separated me from my imagined tormentors. I often slept for maybe an hour or two just before sunrise, and then I would have to slide out of bed and get ready for my teaching internship.

The evening of the prayer meeting finally came. It was out at a retreat center owned by a wealthy family who attended our church. I entered a lodge set into a mountain that overlooked a barn and several ponds—an idyllic setting that I’d been to many times. I felt ready, not scared. Two of my spiritual mentors were there, my pastor’s wife, other elder women from the church. No men—a rarity, since men were typically seen as spiritual heads of churches and families. There was also, I was told, a team of people at their homes praying for me, and if they felt moved, they could call with any messages they received.

There were no spiritual tremors, no speaking in tongues. Gentle hands were placed on my shoulders, my back, the crown of my head. I felt warm and protected. Even now, I can admit there was some beauty to the moment: I was surrounded by women whom I admired at the time, who loved me, who wanted to help set me free. None of us knew that we were simply setting another trap.

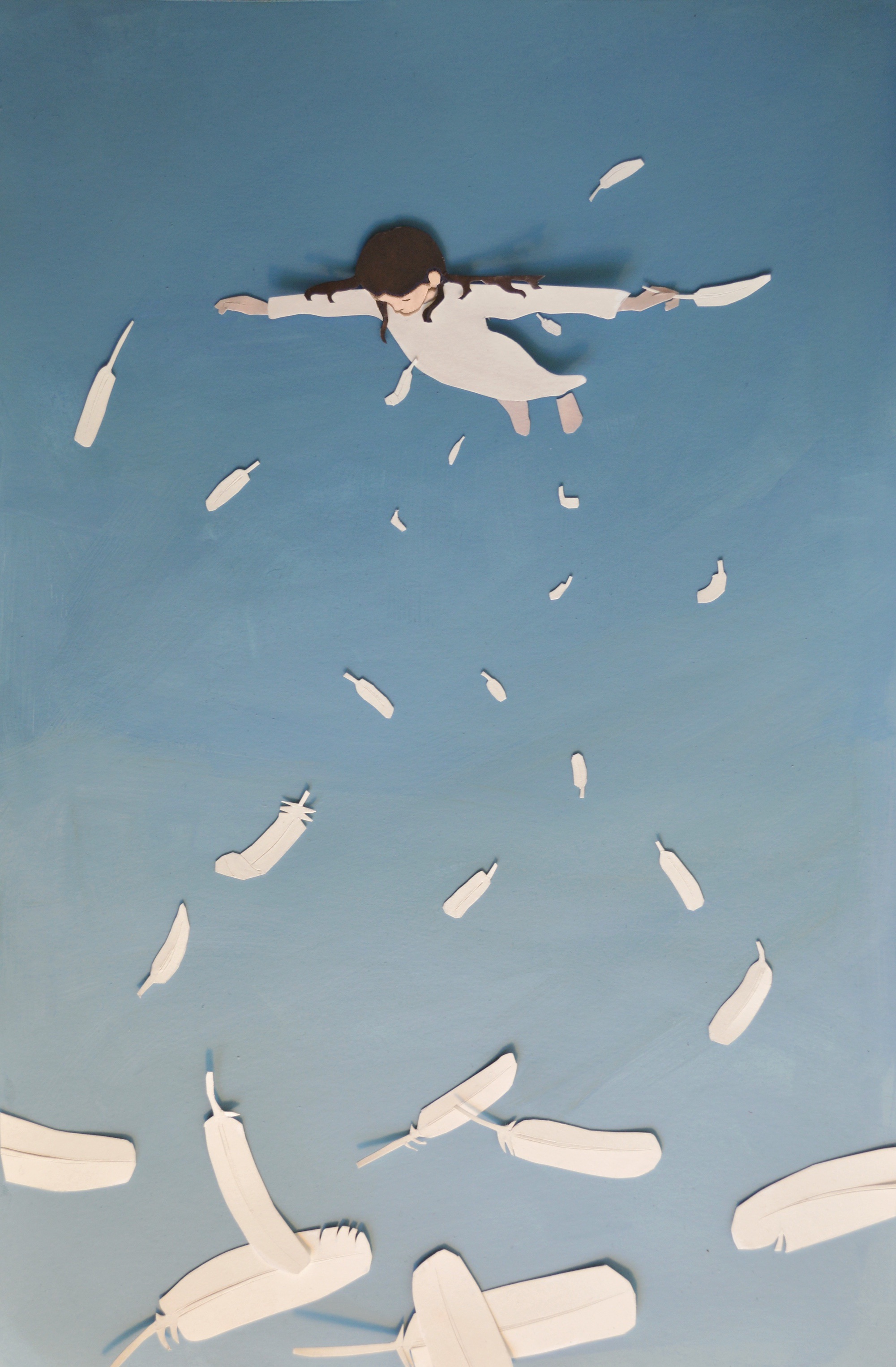

In the middle of the meeting, someone called and said they had a clear vision of the letter M…the word mar, perhaps? It resonated, as it might for anyone with acne scarring and a desire for healing. The pastor’s wife saw a yoke on me in a vision. “I pray in the name of Jesus Christ, by the power of the Holy Spirit, that this burden is lifted,” she said aloud. The other women echoed, “Yes, Lord” and “Amen.” And then I had my own vision: I saw myself spinning and laughing in a sundress in a golden field, like something out of an indie music video or a tampon commercial.

I cried then, and some of the women did too, and we ended with a big group hug. I thanked everyone and drove myself home, singing along to a worship-music CD in my car. I felt giddy and light.

That was it. I was healed. I would be married in a few months. I would be perfect. I would live forever in that field, that dress, that warmth. That blissful, weightless twirl into purity.

But of course, that wasn’t it.

My skin broke out—again. I picked at it—again. I looked at porn—again. I got myself off—again. I would sob. This is just a blip, I promised myself. You’re just stressed. I would pray fervently, study my Bible. I returned regularly to Breaking Free, a study about spiritual warfare by Beth Moore (a woman who had reached a somewhat cultlike status at our church). The study examined various ways people had combated sin and the devil in the Bible, and then guided readers to examine our lives to see which tools we might need to exorcise our own personal demons. I was too afraid to tell any of the spiritual women close to me, those women who’d prayed for me, that I had backslid, because it meant the intervention hadn’t worked. Which meant either their spiritual power was bogus or I was beyond saving.

I did everything I thought I was supposed to do, but I didn’t get actual therapy, talk to a professional about my illness, or otherwise attempt to heal something that wasn’t a spiritual problem at all but rather a symptom of spiritual abuse. I didn’t know that phrase then. In those days, I thought spiritual abuse was only what Catholic priests did to young boys. I didn’t know that the evangelical church’s culture of fear and shame was abusing all of us.

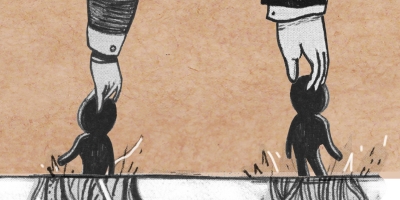

The church indoctrinates children into this culture under the guise of saving them. I escaped this indoctrination until I was a teenager, but once immersed, I was still child enough to soak it up like a sponge. The church also preys on emotionally vulnerable adults like my parents, who were struggling with their marriage and living in near poverty when they were “saved.” My parents’ adult brains (their prefrontal cortexes—responsible for planning, decision-making, personality expression, and social behavior—fully formed) kept them from the same level of shame I suffered. But these brains have also kept them from questioning the church in any way. Neither of them went to college, and while they are intelligent people, they are not educated. They do not have the same sense of nuance and self-reflection, the same comfort with ambiguity.

My parents are also registered Republicans, since it’s the “pro-life” party—this viewpoint yet another influence of the church. They’re Republicans, even though they are working-class and the Republican party has long been the party of the rich and their interests. My dad regurgitates Fox News the same way he regurgitates sermon points. My parents base their voting almost entirely around the issue of abortion, even when a candidate has engaged in far worse sins, like racism or sexual assault. The pack mentality guides their decision making, the same way it has guided white evangelicals all over to vote for and support terrible men and women who run our country, or at the very least to believe that politics don’t matter all that much because God is in control. The ruler of all.

Because my parents’ allegiance to their faith is so strong, I am often afraid for them to read what I write. Sometimes I feel like my experience mirrors that story in the Bible where God tells Abraham to go and kill his son Isaac, and Abraham decides to obey. At the last minute, God tells him not to kill the child, that it was a test. But this is not a test. I don’t want my parents to love me less because I don’t believe the same things they do. Yet I know this is another influence of the church, which claims to be the greatest supporter of family values (unless that family is not Christian or not white or not heterosexual or not American): to pressure your children into religion, even if they don’t want it. To press them about their faith. To insist that any struggle in their life must be a result of their distance from God or lack of church community. That a chemical imbalance or mental illness is nothing to an all-powerful God.

This is a dangerous precedent that leads to far more hopelessness than hope. One that perpetuates cycles of shame and leads women to vote against their own interests, even their own bodies. One that distances people from their loved ones. One that keeps people from getting help, even though untreated depression is the number one cause of suicide. I was lucky that my own suicidal ideations never reached the breaking point. But lucky isn’t a word we ever used as Christians. Luck implied coincidence or chance. It was more of the devil than of God.

After I divorced my first husband—the one I had waited for—I got a tattoo on the back of my neck, a form of catharsis. It was an excerpt of a verse from the book of Isaiah, from a passage often referred to as the Year of God’s Favor. It reads Beauty for ashes in Hebrew, the Biblical version of the phoenix rising.

Years later, a Jewish acquaintance asked me what my tattoo meant, because she recognized the Hebrew letters but not what it said. It turned out that although Hebrew is written right to left, the tattoo was stenciled on from left to right. Unfortunately, not being fluent in or familiar with Hebrew ourselves, neither my tattoo artist nor I knew this at the time. While it bothered me at first to realize I had a tattoo that ultimately meant nothing, eventually the idea grew on me: I could make the meaning. This was a bastardized version of a spiritual truth, just like me.

When I’d told the women in the prayer room about my vision, I said it was like I was dancing with God in that sunlit field, even though there was no one there but me. God was invisible, the way we often imagined Him.

Looking back, I wonder if this vision was a gift from my future self. A message to tell me that I was beautiful, and the world was beautiful, and I was allowed to enjoy it. I wasn’t disgusting or marred or sinful. I was deeply human. I was good and holy and whole. I wasn’t with an invisible male God in that field. I was alone with myself, full of the childlike wonder that I’d lost, or that had been taken from me.

Years of my life have been swallowed—experiences, self-knowledge, time, exploration. I still feel delayed. I grieve daily for things I can never get back: casual dating in my teens and twenties, sexual experiences without shame attached, deep friendships with people who believed different things than me, distance from my church and hometown, choosing a life partner out of love and desire instead of necessity or fear.

How does one arrive at healing? The church says: by denying yourself. So you deny and deny and deny. You deny yourself long enough that you no longer know who you are. When a voice speaks, is it God or the devil or you? Did I want to feel lust or desire because I was told not to? Did I want because I was deprived of something? Or did I want because I was human, real flesh and real blood? Could this humanity coincide with spirituality? What if my deepest desires and needs, the ones I was taught to see as wrong, were the most akin to my spirit?

That still, small voice inside me now moves more loudly through the world. She names her pain. She calls out injustice, when it’s done to her and when it’s done to others. She doesn’t always say yes, because she has learned to say no to what does not serve her. She is more open, available, whole. She is closer to her self than she has ever been. And she can acknowledge how very little she knows, how very little any of us do.

Would you rather feel like part of a community but find yourself mired in fear and shame, or pave a new path all alone and find yourself rooted in hope and love?

It took me a long time to arrive at an answer, but that’s because it’s a faulty question. Along this new path, I have built community around me, people who aren’t in my life out of obligation or proximity but because we chose each other. And we are here, walking together into the unknown.