Nonfiction

At Home with Mr. Unlimited Bear

by Eric Tran

I don’t believe much in the afterlife, but if there were a gay heaven, it might look like the Rainbow In, hidden away in Lake Wylie, South Carolina, where the bouncer—a woman with tight white curls who looked like Sophia from The Golden Girls—offered me bite-size candy from a bowl before sending me down a hallway splattered to its molding with 1950s centerfolds of all genders, to a small stage with black brocade velvet curtains where, later, an instrumental “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” cued the lights to rise, and there, flanked by a glittering chandelier and a portable stripper pole, was Stone Parque, wearing a web of purple-and-gold Mardi Gras beads glue-gunned into a makeshift thong and, though he was in his forties, a wry, boyish smile.

I say the bar might look like gay heaven because I suppose it depends on what kind of queer karma you’re looking to accumulate. Online reviews for the Rainbow In split between those who drank the rainbow Kool-Aid (“Come here, everyone’s gay”) and their Kinsey-scale opposites (“Don’t come here! Everyone’s gay!”). The Rainbow In understood its push and pull. A sign on the entrance read, “The Rainbow In is a gay establishment. Do not come in if you are not comfortable with this.” The bouncer, at her full five feet tall, acted as Saint Peter, sizing you up through a security camera before buzzing you in.

Perhaps this was to be expected. The bar was a short drive from North Carolina’s gay metropolis, Charlotte (nicknamed “the Queen City” by its gays and straights alike), but was actually in a small suburb in South Carolina. The area is fairly affluent, but on my drive in, I saw endless desolate hamlets while listening to NPR report on North Carolina’s proposal to ban same-sex marriage—really, the typical kind of conservative hellscape coastal elites (see: me) often associate with the South.

I grew up in a part of California where heterosexuality, in its purest, whole-milk form, was considered passé. And when I moved to North Carolina for graduate school in 2010, I became, as the poets say, really fucking depressed. There was one official gay club in Wilmington, my new home for at least a handful of years, that served every city in a three-hour radius. Nearly all the gay men there were white. As an Asian man from a city of majority immigrant families, I couldn’t imagine myself surviving there.

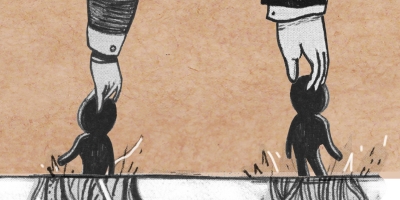

But like a moth to a fluorescent light, I kept trying. And at that single Wilmington gay club on a lonely weekday, I saw a flyer for the finals for the Mr. South Carolina Unlimited Bear pageant, to be held at the Rainbow In. For those not in the know, bears are a gay subculture of large—often fat—gay men. Groups emerged in the 1980s as a resistance to the gay obsession with smooth, skinny youth. They made uniforms of leather harnesses and communicated mating calls with a woof. In California, I saw beardom as a celebration, if also a loving parody, of self. And here they were in my new not-yet-home, not incidentally or casually or quietly, but in an ad for a pageant where grown-ass men wear sashes and velvet and crowns. Tacky, regal. Outcasts, proud. They are bear, hear them woof.

After seeing that flyer, I emailed Stone Parque, who had won the last Mr. South Carolina Unlimited Bear title despite the fact that he, while adherent to the size guidelines of bears, had nary a stitch of fur on him. (The internet hosts dozens upon dozens of pictures of him nude and leaning against a beam in a farmhouse, or nude and posing on a shag rug, or nude with pageant sashes draped just so.) On the surface, I wanted to hear the history of his dueling identities: a Southern-born gay man, a follicle-free bear. Not just surviving, as the saying goes, but thriving. But the subtext of my email was: Help, I’m so unhappy.

Perhaps I could have eschewed the subtext and gone right for all caps. After all, Stone advertises himself as the kind of man who lays it all bare, so to speak. He met with me before the pageant, wearing a black leather kilt and matching combat boots. Immediately, he pulled me into a long embrace that was warm and slightly damp, like spring nights turning into summer. His bald head and chest, without even a whiff of a tan, bolded his blue eyes. Imagine a pair of lighthouses in the distance.

“Yeah, I’m not hairy,” he said before I could ask much, “but neither was Fuzzy Wuzzy.” The conversation vacillated between soundbites like that and epic tales, which he prefaced with a large inhale and “Now let me tell you a story.” Like when his mother swore his male partners (Stone is polyamorous) would never be invited to her house, but later recanted after meeting one of them, and they reconciled when Stone performed one of her favorite Elvis songs at a pageant. Now Stone and his husband help out on the family farm. All of his stories generally hinge on a principle he repeats: “If you hide anything, that’s when people hate you the worst, because they feel betrayed.” It sounds like a warning, but it’s the opposite—the more honest you are, he implies, the more success you’ll have. The bear community, he told me, never batted an eye at his furless complexion.

He was generous with extraneous details, from the lineages of various drag-queen families to explanations of allegedly resolved feuds that still warranted disgruntled mention. Part of me chalked this up to Southern conversation protocols that I had yet to master. (At another point in the conversation, he recalled how another contestant really “shined out” and “showed his ass,” which did not, as I assumed, mean that a charismatic bear had dropped his drawers, but rather that he’d acted shamefully.) But for all the detail at the periphery of Stone’s stories, they were a bit anemic at their dénouements: everything got better without any revelation of how we got there.

I bring this up because he never seemed insincere. In fact, though his phone’s text-message alerts pinged with histrionic frequency, he looked only at me when we talked, and at several points he literally took my hands in his to emphasize the importance of what he was saying. But his answers did feel rehearsed, like I was a judge for a pageant interview. He skated, however elegantly, past the number of times he’s been fired since coming out. Most notably, he had been a preacher in a small Southern town and was not only fired but also personally chastised and escorted out by the church’s pastor. He didn’t linger on the story, but I still picture him walking past silent pews, shoulders hunched forward as if bearing the entire congregation’s projected shame. During our conversation, he still made references to God’s blessings but never to returning to the Holy Word in an official way. It seemed impolite, even to a new Southerner like me, to ask about how someone was coping with the loss of a core tenet of their being, to see a hole in someone’s stomach and ask to stick my hand in to inspect it.

Certainly Stone has had a fair amount of redemption since, turning what was an unloved part of him into an identity that has won him literal crowns, but I wasn’t sure—and perhaps am still not—how far that compensation goes. After Stone left to prepare for the show, some loud patrons’ conversation made it clear that they were not there to support the Mr. Unlimited Bear pageant. One of them said snidely to his friend, “I don’t understand Stone Parque—aren’t bears supposed to be hairy?” I opened my mouth to respond, but then my jaw closed quietly. Stone may have left some of his sweat and glitter on my hands, but not much of his confidence came with it. The man and his friend left the rest of their beers to go elsewhere, and all I could do was stir my drink until the ice gave way to melt.

One way to think about the Mr. Unlimited Bear pageant system: it’s as if the love child of drag queens and Miss America had a habit of anabolic testosterone. Title holders and neophytes are expected to make the rounds at regional pageants or other events. And not just meet and greets, but entire stage routines, with choreography to some generic, booming, and admittedly empowering gay anthem and custom costumes that appeal to Southern tradition and gaudiness.

That night in 2011, one bear performed to “Footloose” in a red leather harness–Speedo combo, legs flailing above his head like a marionette with an exhibitionist streak. But Stone chose Toby Keith’s “Red Solo Cup.” Not a song I would consider in any way fabulous, but he performed it wearing his beaded thong and crooning to an empty plastic cup, tipping it to his lips like some dreamy lover. It was easy but not mundane. Radical: a queer man enjoying the everyday in physical and emotional nudity. He accepted the audience’s tips by taking each person’s outstretched hand in both of his. He looked intimately into each person’s eyes as if their attention, and not at all the money, were what made him rich.

A handful of contestants vied to be Stone’s successor. One was a tall bear with a full, red beard who wore an old-school cop uniform that made him look like he stepped out of a porno parody of CHiPs. Another donned a vintage blue cheerleading tracksuit, but he was nervous, stuttering so much that his cheer felt more like staring at a Boggle board than like a rallying cry.

Between these bears’ talent and interview sections, Stone referenced Amendment 1, the ban on same-sex marriage then being considered in North Carolina. South Carolina had passed a similar amendment back in 2006 with more than three-quarters of voters backing the bill. Even in North Carolina’s most progressive years, in the previous millennium, it probably would have passed. He talked about fighting it, of course. Calling friends and family members, going out to vote, speaking out whenever possible. He repeated, “This is our home.” He meant this is our state and we deserve to be represented, but he also meant this will be our state, our home, regardless of the outcome.

I thought it a little naive, too trusting, and if I’m honest now, it was more than I was capable of. In 2008, a few years earlier, California had voted on Proposition 8, a similar same-sex marriage ban. At the time, I’d been studying abroad in England, an Obama pin affixed to my lapel so the Brits would know I was the right kind of American. My friends there—both the English and my American classmates—assumed California had always approved of gay marriage.

On election night, we huddled around CNN with a flat of beers each the size of my forearm. We Americans felt smug because for once we were in the know about politics. The Brits were smug because they were young and beautiful and rowdy; they called out commentary on each result as if they were experts. “Fucking Wyoming!” one shouted as it went Republican, though a few minutes earlier he hadn’t even known Wyoming was landlocked.

But it didn’t matter, really. What mattered was that they cared and that we cared. Each time a battleground state was announced, you could hear us all sucking in a bit of air, as if to brace ourselves. Louisiana: McCain. Florida: Obama. Montana: McCain. North Carolina: just barely Obama.

Around 3:00 AM, the commentators announced that Virginia could very well decide the election; a win for Obama would seal his presidency. My colossal beer had warmed in my hand but still I took nervous little sips. The commentators repeated the stakes several more times, most likely to fill space while the results came in, but they were also building tension—my grip on my beer can had formed little dents in the tin. Then: Virginia for Obama. He was the next US president.

We rushed outside, and somehow sparklers emerged, and we all grabbed some in each hand and started running around the quad. It was late, five hours ahead of the East Coast, but in the middle of the dead, quiet night, we shouted and waved the sparklers above our heads until the porter chased us off.

Afterward, I waited for the Californian results to come in, but since the state was clearly going to go to Obama, news coverage started to wrap up, and my friends, English and American alike, went to bed. The Americans and I went to a college in California that hosted the largest No on Prop 8 phone banks in the area, but no one in the dorm seemed particularly invested, possibly because they thought it was so likely to fail, possibly because none of them were gay. Only I still waited. A transatlantic celebration had become a private struggle.

It was morning, actual daylight morning, when the results were called: by a narrow but decisive margin, Prop 8 had passed. Same-sex marriage was outlawed in California, home to San Francisco and LA, the perpetual lands of fruits and nuts, the summer of love. My home.

Or what was supposed to be home. After the election, I could excise friends who supported the proposition—if you don’t love this part of me, you don’t love all of me—but how could I divorce myself from where I grew up? I still couldn’t understand what had happened. I knew parts of the state were conservative, but I still always felt like I could be who I was. Prop 8 made me think maybe I was wrong, maybe I didn’t understand the place I lived at all. Maybe we were strangers or maybe we once were close but had grown apart. In twenty years, I had never considered leaving, but maybe the state was rejecting me. I could not face the numbers like Stone Parque insinuated he could at the pageant. Each vote cast for Prop 8 seemed to be addressed directly to me. Leave, leave, leave, seven million times over.

Even years after I first moved from California to the South, people asked, incredulously, why. My answer wanted to be another question: Why not? North Carolina, while it didn’t initially deliver much to quench my thirst as a young gay man, also never promised me much. And in that way, it had yet to betray me.

I understand that same-sex marriage is not the only, or really even the most important, fight for queer people. After all, marriage doesn’t directly impede violence against us or prevent us from being shunned by our families. But it stands as validation, a way of being seen in both legal and cultural ways. And for so long, if a place denied me that, it was not home.

I have heard in passing—and therefore have likely misunderstood—a German word, Sehnsucht, which denotes a longing for a far-off place or home. It’s a stronger and more nebulous feeling than nostalgia or homesickness: with Sehnsucht, the desire is for a place that no longer exists or probably doesn’t exist at all, the place between the ideal home and the now. And in the longing a new space is made, one furnished by loneliness and the very fine, possibly perverse, pleasure of having thought of something so beautiful and great that it causes you pain. I think of it as the unshakable, almost invigorating, chill after getting caught in freezing rain.

I never asked Stone why he didn’t leave the South or really even the tricounty area. Perhaps it was out of politeness, but more likely I already knew he wasn’t the kind of man to leave home, even when it became hostile. His, or at least my, Sehnsucht is for a home where being yourself doesn’t prompt a sound rejection.

I don’t mean that he settled, not necessarily. I mean that there is no place where we are safe from being hated. And by the same token, if we are hated everywhere, we can stake our claim anywhere and combat the consequences. The Rainbow In posted a warning that it was a gay establishment, but laced in that defensiveness was pride: it deserved to be there, and God damn it, it would take up all the fabulous space it wanted. I mean that staying can be a radical act. That home can be where you demand space, even if you’re not given it, that Stone looked at an embodiment of prejudice and unfiltered bigotry and asked to embrace it with his formidable, loving arms.

The pageant ended the same way many good things in life do: with a little bit of nudity. The finalists lined up in their “bear wear,” which Stone described to me as a sexier, trashier version of formal wear. One donned the persona of a motorcycle daddy, with the leather pants and open vest, the matching hat and perforated gloves. He seemed more than slightly anxious, as if an accessory out of place might be an omen of his defeat. At the other end of the spectrum, one wore a camo jockstrap and a leather harness; he reddened at the first catcall shouted his way. Whether they felt physically uncomfortable in the various tight fabrics and sequins or were nervous about the results, none of them looked particularly at home.

I don’t mean to criticize. Their costumes were impressive and indeed struck that joyful balance between trashiness and sex appeal. But they were not Stone, or at least not yet. And this is to say I was also not Stone. Understanding how he summoned a combination of faith and love and outright denial for a place that wanted him gone is different from enacting it. After the pageant that night, I would drive back to my house and for many days continue to be, to reinforce that artful term, really fucking depressed.

But since the night was supposed to be about celebration, let’s return to something positive: the finalists for Mr. South Carolina Unlimited Bear onstage, in various levels of undress, staring out at the audience, which had swelled nearly to the building’s capacity, so supportive or invested or drunk (or all three) that they hollered for every twitch the contestants made; that glorious, unbearable tension, the fondant-sweet smiles of the contestants, thinking that they were so close to winning, that under those merciless spotlights, anything might be possible.

Note: Since this essay was written, the Rainbow In has closed.