Fiction

Family Economics

by Nicholas Grider

The telegenic, athletic-seeming man stares directly into the fat-lensed video camera, blinks, stares a bit more, then answers the question. Well there’s corn, he says in a firm, slightly metallic baritone, and beyond that there’s more corn, and it’s not just corn, there’s wheat, there’s a bit of wheat, and there’s a lot of soybeans, but the soybeans aren’t really much to look at compared to the wheat and the corn, you know, you really know what it is you’re looking at when you’re looking at corn this time of year—and at this the man pauses to swallow and approximate a toddler’s simple grin, then continues, his stare unerringly direct—but that’s not really me, I’m from here and live near town with my family and work in the next town over, but I don’t work the land, I just see the corn when it blurs by on the side roads I sometimes take home, at this time of year they seem like tunnels. At this he stops, lifting his eyebrows into arcs, and looks off-camera as if shy and unused to being interviewed, saying, Well, but actually what, what again was your question? You wanted to know who I voted for? You want to know how I make a living, where I live, something about demographics, about my opinion, meaning you want to know my opinions, or what I do or don’t have an opinion about? What I make happen in the world and what happens to me? Does that matter a whole lot more, the man asks, tugging a bit at his striped navy-and-maroon tie with a pink-pale, clean-fingernailed hand, than a blur of autumn corn?

Once, when the older son of the interviewed man walked from school to the local bank after soccer practice and the teller asked him how it was he had all this cash to deposit once or twice a month, the son simply smiled an echo of his father’s smile and said it was for work at home, that there was a lot of work and his father was very generous, and the teller, a breezy woman named Helen whose girl was in the same grade as the boy’s brother, was unsatisfied with the answer but told the boy it was great he was a hard worker and he was lucky to have such a generous father, and in reply the boy simply nodded and nudged the crumpled bills closer to her.

The telegenic father’s name was Adam Cooper, and he was tall and lean and on the shy side of middle-aged, and his head was crowned with a clipped puff of sun-blond hair already beginning to thin. He carried a slim gray briefcase he rarely opened to and from work, and invariably, stopped in one town or another and dressed in the modestly stylish way he was and driving the modest luxury car he drove, he seemed to evade stereotypes outsiders might have about locals, albeit not deliberately, and so was easily noticed by footage-gatherers who were not from the patch of the Midwest he’d grown up in and moved away from for medical school and moved back to a decade ago in order to open up his practice. They’d stop him and ask him about himself and his opinions, his thoughts about the news and the nation and beliefs and religion and the future and what victory means and what support means and what unwavering support means and more. When this happened, he’d lean in a bit, sometimes physically but mostly with his voice and his widened eyes, and supply a small mockery of the open-sky earnestness the reporters had come here to document, allowing memories of grandparents long dead to ventriloquize him into a homespun parody of himself right on the verge of an aw shucks, seconds away from describing a tractor he did not actually own or inviting you to a church picnic behind a gleaming white wooden church in caramel fields on the outskirts of town.

Dr. Cooper and his sons did not attend church, though, at least not in the habitual way of people for whom faith in the unseen is central, but they regularly put in an appearance because many of the congregants were elderly and it was good for business, as Dr. Cooper told his sons. But he didn’t admit this in his grandparents’ depthless twang when queried on film, having been chosen because he seemed like he might be an urban sophisticate seeking bland refuge in a part of the country blanketed in some cross of crops, snow, and brief, meaningless names. Dr. Cooper never showed his annoyance when probed, or admitted to complexity, but even if he were honest he’d maybe just say, Well, you know how it is, medicine is a business, and every business has a bottom line. Of course I want to help people, but I do have a family to feed. Dr. Cooper was stopped more often than he thought a person as unremarkable as him ought to be, but if you were to ask him about it later when he was at home, shirtsleeves rolled up and bourbon in hand, he’d say he was pretty sure he’d never broken character, that it wasn’t all that hard, and that anyway, it’s never mattered to anyone what he said—they weren’t looking for information, they were looking to fill airtime for viewers with only half an eye on the constant flash of news to begin with.

Once, on an early spring Sunday mild but too windy in a stinging way for Dr. Cooper to want to head out on one of his vaguely planned long-distance rides on the lightweight aluminum bike his wife had given him the final Christmas she’d spent with the family before returning to Chicago, Dr. Cooper decided instead to avoid any demands related to an extended stint in public and instead sat in the den, flipping through modestly glossy national magazines to which he subscribed but which he rarely read, keeping half an ear on his younger son practicing what the teacher had told him via email was a Scarlatti sonata for a piano recital later that spring.

Dr. Cooper rarely saw the teacher because the ambiguously young woman, a thickly cheerful woman named Alexis who called herself Lex and whose short bob of brown hair was subtly streaked with auburn in a way Dr. Cooper found intriguing, told him that she was more than happy to give his boys piano lessons, but due to some reasons she simply explained as “boringly ornate,” she’d be unable to give the lessons on weekends, when Dr. Cooper was at home, so while she did sometimes visit, more often the boys would stop by her studio in town, only about four short, safe blocks from their unspectacular but adequate school. She’d told Dr. Cooper he was more than welcome to accompany his sons and wait in the waiting room, but when he did so, he found that the small room––a modified living room in a two-story home whose soundproofed bedrooms acted as studios––was claustrophobic, given the flux of children and parents in and out and what seemed like the near-constant presence of Alexis’s fiancé Ted, an administrator in the large music program of the state school about forty minutes away whose exact title Dr. Cooper couldn’t recall. While Ted seemed nice, Dr. Cooper disliked his tendency to linger in the waiting room and the lopsided way in which they’d engage in small talk––Ted would pose a neutral question in a neutral way to the amiable doctor, but upon receiving a reply he’d simply offer some neutral variant of That’s very interesting, before pausing, then posing another question only sometimes related to the previous one. Given Dr. Cooper’s not-quite-bothersome discomfort in the waiting room, his trust in his boys, and the demands on his time, he’d long since decided to simply let the boys attend lessons on their own, especially after Alexis offered that Ted would be more than happy to drive them home.

Now Dr. Cooper sat half-sunken into the plush couch in the den, dressed only a little less formally than when at work, his slightly worn loafers looking yellowish pressed against the edge of the reddish-brown mahogany coffee table on which lay an expensive bowl of fake fruit and over a dozen magazines and several more medical journals, the print versions of which Dr. Cooper preferred over the digital access included in the subscription, all arranged on the table in a way meant to seem casual rather than sloppy. His face shifted subtly between a squint, a frown, and arched eyebrows, sometimes lingering somewhere between the three as he sat absorbed in a lyrical but highly informative personal essay about young adulthood, left-handedness, Catholicism, topographical isolation, overlapping traces of colonialism, and what the author called “internalized nationalism” in the section of northwestern Uruguay about which the author was writing.

Dr. Cooper’s attention broke when there was an abrupt and lengthy pause in Evan’s iterations of the toothless Scarlatti. After a silence long enough for Dr. Cooper to twist around and call over to ask whether everything was okay (to which Evan responded with a genuine-seeming Yup!), Dr. Cooper returned to the article, wondering whether the piece constituted a kind of unintentional advertisement, which led him to consider a trip to South America––if not to Uruguay, then to somewhere where Dr. Cooper and his sons could ease into the culture more fluidly––before flipping to the next article. He rolled his eyes. It was of a genre Cooper thought of as “shocking revelations that people are human,” in this case an article about the history of socialism in the northern Appalachians, and Dr. Cooper was almost ready to give up when he was interrupted, not unhappily, by his older son Andrew as Scarlatti continued to hesitantly twinkle in the distance.

Andrew looked at his father with half a smile and paused before making a simple request. Father, he said, is it okay if I borrow the handcuffs for a while?

The handcuffs to which he was referring were one pair of several Dr. Cooper had inherited from his police-officer father, who both purchased them for actual use and collected reproductions of antique handcuffs from around the world. Without frowning at the question, Dr. Cooper simply asked his son why, after which his son, on the other side of a long pause, simply responded, Practice.

This sufficed for the doctor, so he closed the magazine without marking his place and set it down carefully on the coffee table and stood, stretching his back before gesturing to his son to lead the way to the metal box in his office where he kept the assorted and almost entirely ignored restraints, and when he returned to his study he decided he wasn’t in the mood for any more elegant information. Instead, after a quick check in the kitchen and a less quick check of himself in the mirror, he carefully stowed the wire-rimmed glasses he told people he only needed for reading and, smoothing his hair a bit and shrugging into his black puffer, grabbed his keys from the bowl in the foyer. He called out to Evan that he was headed to the store to get supplies for fruit salad, did his son want any, and he smiled in pride when his son said yes and then quickly thanked his father, needing neither to be prompted for the thank you nor to pause his push through the Adagio of the Scarlatti.

No one has ever asked the man, and so he has never told the story of how he didn’t grow up intending to become a primary care physician (or family doctor, as they still call it where he lives), that actually he was a prizewinning violinist, neither a folksy fiddler nor a prodigy but good and persistent enough that professionals who taught at nearby universities told him that with discipline he could become a professional himself. The small, mostly calm, happy family he grew up in never asked him why he abruptly stopped when he got to college, or if they did ask, he simply shifted the subject away from the wire-string redwood cloud long since gathering neglect in a closet to what it was that the violin had taught him, glistening under various stage lights as he complexly bent one or more of four available strings. It had taught him two things. First, the hours of practice taught him that discipline pays dividends, and second, the struggle toward impossible perfection taught him it was important to know your limits––everything in life comes at the cost of something else, he’d say, at which point he’d shift again and talk about limits besides the limits of his fingers, the limits of his patience, or the limits of his violin.

His wife, Ada, whom he’d met as a resident in Chicago and who had left quietly during a dark winter five years back for reasons Dr. Cooper declined to discuss, knew he used to play but never considered it important enough to ask about, and his two sons, Evan and Andrew, ages ten and twelve, respectively, likely wouldn’t believe it if anyone tried to convince them of their father’s musical background, much less how it had shaped him, though both boys had taken years of piano lessons and were modestly talented, the more focused and persistent Andrew being the better of the two. Their skill was such that their father could take pride in how they impressed anyone who heard them play while resting assured they weren’t talented enough to consider music as a career. As he’d sometimes say to various lenses, especially during election seasons, it’s important not to stray too far from the roads of pragmatism and responsibility, because in wide-open places like this, you can easily get lost.

Once, a little wide-eyed in the usual way, when stopped by a film crew for his opinion on some recent news while nursing a hangover, he let a little bit of his caustic sense of humor bleed through when answering a question, saying, Oh golly no, sir, I don’t beat my sons—I have them beat each other. They’re good at it, and it saves my shoulder, which I hurt in the church softball-league championship game. The film crew got quiet enough that Dr. Cooper knew they weren’t sure whether he was kidding or not, and he was content to let it stay that way; anyone who knew the doctor knew, if they knew anything about him at all, that when he was serious about something, his seriousness, like his charm and his unwavering focus, was as plain as his affected twang.

Just like he found himself echoing his grandparents when asked to represent his patch of the Midwest, he sometimes found himself echoing his father (quiet and stout, still police captain in a town a half hour to the west but mostly at this point an administrator) when talking to his boys on Friday nights, walking them out behind a rooster-red and tooth-white clapboard shed at the far corner of the lot never entered except by the gardeners who kept the land looking like a lawn and not just like the unused ground between home and commerce of the former farm it was.

As it was when he was young, Friday nights were both work nights and game nights, though Dr. Cooper had refined, by adding an element of choice, the game his father had invented for him and his bookish older brother Douglas, dead at seventeen for reasons the friendly doctor declined to discuss the way he declined to discuss much of his childhood and the absence of his wife. The game of work was important, because, the doctor would tell his modestly talented sons on Friday nights, after all, you’re both old enough to know that nobody’s innocent, and most of what you get you need to earn.

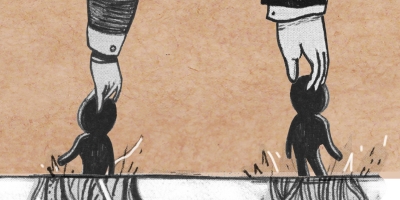

Carrying a billfold stuffed with wrinkled cash and a black metal banker’s box big enough to hold part of the police gear inherited from his father, he’d walk his sons out, sharing his day with them and asking them about the victories and defeats of their week, not in the homespun way he affected on film but with fatherly warmth and genuine interest, and once they were out of sight of all but each other and the fields of maize the doctor had let grow into wild spikes, he’d tell them to take off their shirts and hold up the half-dollar coins each boy possessed and ask them whose turn it was––not because he’d forgotten, but in order to see if he could catch them in a lie, though they were, to their father’s pride, unwaveringly honest.

Then Dr. Cooper would set the box down on a thin pillow of sometimes snowy lawn and open it, lifting out the police-standard kind of handcuffs his older son sometimes requested as well as a half-collapsed box of double-edged razors and a tan strap of leather about the size of an adult man’s belt but lacking loopholes and sharpened to a point at one end, all while asking his boys whether they’d had any insights about the game before they got started, but mostly, to his mild disappointment, they had not. And it wasn’t really a game, except for the game of chance involved in the coin toss. How it worked was the family doctor would ask the son whose turn it was to call heads or tails and tell him which option he chose: did he want to be beaten with the strap and given fifty dollars, or did he want to be handcuffed and locked in the shed overnight and only get paid twenty?

It wasn’t punishment, he reminded them, or it wasn’t merely punishment, it was work, though of course some toughening up would serve them well, as one of the biggest problems of an uncle the boys would never meet was a lack of resilience. The razors were for the boys to hold between their teeth in order to discourage complaint and encourage focus, but before the doctor’s sons each gingerly bit down on one, the boy whose turn it was would offer his preference and state whether he wanted to attach the option to heads or tails. While there didn’t seem to be a pattern to which side of the coin each boy chose, the boy whose turn it was always, much to the good doctor’s satisfaction, chose the fifty dollars over the twenty, though as he’d remind them every Friday night, the pale sun at a variety of slants, chance was always a factor, and there was a difference between claiming what you wanted from life and making do with whatever life chose to provide.