Nonfiction

Make You Disappear

by Stacie Williams

If you hadn’t disappeared, we might not have thought anything about you unless we knew you personally, had laughed with you while sipping overpriced drinks at trendy bars, shared chain emails with you at work detailing our life ambitions and five dumb facts about our favorite TV shows, or given you hugs on holidays in rooms overpowered with the smells of cinnamon, onions, and roasting things.

But when you went missing, and then your face—young and brown like ours—appeared on the front page of the newspapers, we had to talk about you. When had missing black women ever made the nightly news or the national papers? We had to say your name. Had to see if we could figure out what went wrong, what might have been responsible for your absence, which was loud as an earthquake and just as devastating. Why didn’t you answer your phone for one hour, then two hours, then ten hours? We racked our brains for reasons why we personally might go so long out of touch in an overconnected world. “Maybe her phone fell in the toilet,” we tried to reason, hoping to solve the mystery ourselves and bring you back. You, who could have been a sister or a best friend.

The city, so vast when viewed from a plane or the top of a skyscraper, is really very small on the ground, block by block where the wind slices through, revealing all of our vulnerabilities. We probably went to the same parties, listened to house music, went to the same 4:00 AM breakfast spots, trained for the same marathons, dated two degrees of the same people. We were the same age—not quite thirty, but close enough to it that we started affecting a world-weary air. We know things. Don’t we? We went off to our colleges and worked our first terrible jobs where we learned that we weren’t really as special as we thought we were. We were all single in a big city, and there were attractive men everywhere saying hi and asking to dance and offering dates to all the hot new restaurants where people fused together Asian and Latinx dishes to mostly mixed results. It was a very good time. And even though Sex and the City had ended a few years earlier, that whole era still hung over us. A heady perfume of play and intrigue with sharp notes of cynicism misted over all of our interactions. Hadn’t we done all this before with dating? Or had we simply experienced it via these four white women on TV, with their unsubtle puns and thousand-dollar dresses?

It was nearly autumn, but the air was still oven-hot. When the police found your car, empty save for your purse (“No one would purposely leave her purse behind,” we said), our loud talk turned to whispers. A sense of inevitability crept around the corners of our conversations, quiet as vapor. Chilled us. Made us doubt things we thought we knew. “Do I know someone who could make me disappear?” we asked ourselves. “Is there someone who I’ve smiled with, shared my body with, cried over, who cares so little for me that he could make me vanish, turn me into a ghost?”

Before you disappeared, we all spent time dating men who were outside of the usual scope of people we were attracted to. In the beginning, it was fun. There were men who dressed well, men who smelled really good, men who had good taste in music and books, men who worked with their hands all day, men who got a nice cut of someone else’s money just by hitting a few buttons on a computer, men who could dance, men who had lots of stamps in their passports, men who knew where all the good taco places were. We almost hated to admit (to ourselves) that eventually it felt like a job.

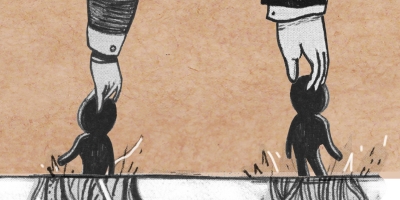

We were also increasingly meeting men who made us feel uneasy. One of us met a guy who wouldn’t stop calling, even after she said she wasn’t interested. He found out where she worked and left persistent messages on her company voice mail, some pleading, some threatening. Another one of us met a guy who wanted to go parking on a particularly desolate spot of lakefront and locked the door until we yelled that he “better open it up.” One of us met a guy who punched her in the arm when she refused to give him her number. Even men we weren’t trying to date made us uneasy. One of us had a routine meeting with a professor that took an unexpected and unpleasant turn when the professor closed the door behind him and started asking her how many times a week she was having sex. There were strange men everywhere who followed too close or looked too long and in some cases didn’t ask for a yes or wait for a no, who just took and took.

After you disappeared, we began to realize the stories we were telling ourselves and others were feel-good fictions. An evening with a suitor that ended uneventfully was merely luck. Our laughter about bad dates quieted. No more happy-hour recaps of Saturday nights in which we painted ourselves as the gallant, witty heroines deigning to give these hapless, handsome would-bes a chance. Mediocre men in the fray who were teetering on the line of our affection or our antipathy were given second chances. Anything was better than the alternative. Of starting over with the kind of person who could erase you, if that was what happened.

We continued to talk about you. Your face was in the papers and on TV every night. Not to mention the blogs, social media, the radio. We would go running in pairs, and your face, your smile full of confidence and secrets, was plastered on flyers for the length of the trail. Just in case we forgot. But how could we forget you? We looked into the mirror every morning and saw your face staring back at us. We spoke of statistics and what little we knew of forensics from watching Law & Order. You did not come back to the people who loved you. They pleaded for your return. We called our parents and siblings in the evenings and told them we loved them, just in case. We still ached for connection and understood that we sometimes looked for it in the wrong places. We expected heartbreak, but also to still be a part of the world. To be a voice in someone’s ear. To touch and be touched. To be seen.

We were at work when they found you a couple of weeks later. What we allowed ourselves to comprehend in a lightning-fast thought, quickly contained and extinguished, was that it had been very hot outside and it had rained for some days. Reality is ugly and terrifying, then and now. We are scared of people we know and people we do not know. We are scared of our ourselves and our humanity. The fact that we sometimes choose the wrong person. Or the wrong person chooses us. That maybe we don’t know what we don’t know until it’s too late to warn anybody else. We can’t reduce you to a simple warning because when we look in our mirrors at the end of another thankfully uneventful evening, we see your face. We won’t forget you. We carry you with us. We see you.