Fiction

In Order to Form A More Perfect Union

by Nina Sudhakar

Layla lived over a quarter of her life with the sensation of a phantom limb before her parents told her there was, indeed, a very real part of her missing. She’d reached an age when family secrets come out, and this one did casually, over a pre-dinner cocktail at her parents’ house, when she mentioned that her employer had asked for a copy of her birth certificate. On the day she was born in a small general hospital in Ohio, her parents said, they’d counted her fingers and toes (all there), pressed their fingers to her veiny, nearly transparent chest and felt her heart beating (all steady). The baby was then immediately snatched away by a stocky nurse who swaddled her in a pink knit blanket and matching beanie and said something about a newborn ward before disappearing.

A smartly dressed woman came by soon after with a series of birth registration questions, which Layla’s parents duly answered. They glanced furtively at each other before saying the baby’s name in unison, the first time they’d said it aloud in full. They spelled their places of birth over and over until the woman said, Can you just write it down here, please? The cities each had over a million inhabitants, but listed alone on the woman’s blank page, they looked like dreamt-up villages on a remote island. And the country too, she’d said, passing her clipboard back to them as Layla’s parents wondered what the woman had heard when they’d said, quite clearly, India.

A month later, an official-looking envelope arrived with Layla’s typewritten birth certificate inside. Her parents were relieved to find that all the information had been entered and spelled correctly. But inside the envelope they also found an additional certificate that was blurred like a poor photocopy. It was nearly identical, save for the name and place of birth. The girl this certificate belonged to was called Shayla, and she was listed as being born to Layla’s parents in India.

For several days, they ignored the extra certificate. They did not trust their eyes from lack of sleep. The baby continued to need and want with increasing clamor. But the document’s details never resolved into the proper orientation, no matter how many times they looked at it.

One evening, while Layla’s mother was feeding the baby, her father called the local records office to ask about the discrepancy. Though both of them spoke perfect English, Layla’s father knew his wife was self-conscious about her accent. She would never have made the call herself. The man who picked up put Layla’s father on hold for at least fifteen minutes. Layla’s father tried to let the feeble jazz hold music soothe him like one of his daughter’s lullaby recordings. When the man returned, he said he was transferring the call to someone who could help. There were several clicks before another man came on. This one’s voice was deeper, more authoritative; he seemed to be in charge of something.

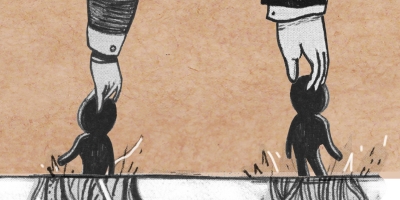

The man introduced himself as lead scientist for the research-and-development division of the Department of Homeland Security. He explained that Layla’s parents were part of an ongoing twin study. Though Layla’s father felt stupid saying so, he thought it necessary to point out that he and his wife had not had twins, that they hadn’t consented to any such study. The man’s voice slowed as he answered, as if he were speaking to a small child. The study is mandatory for the affected class, he said. As part of the study we make the clone—or twin, as we call them. Rather, we send the genetic data to your native country where the twin is then made.

There was an extended pause as Layla’s father determined which of his many questions to ask next.

It’s policy, the man said, not unkindly. My hands are tied. Then he hung up.

The night after her parents told her this story, Layla dreamt of her twin. The girl was the same size and shape as her, but there was something odd about her face. Her features were glossed over, as if they were part of a mask. Layla was running through a white corridor lined with black doors that looked like knocked-out teeth. All of the doors were locked and none had knobs. The girl was a demon grown from Layla’s own rib that stalked her, haunting her peripheral vision. When Layla reached the end of the hall, she spun around, slapping the mask from her twin’s head. She half expected to see a mirror, but instead of a face there was only a chasm, a dark, bottomless void.

On the seventy-third page of her search-engine results, Layla found a promising reference to the twin study. Whereas all the other results had directed her to psychology departments and peer-reviewed articles, this link led to a batshit corner of the internet reserved for conspiracy theories. Buried in a highly active message board was a comment from some user five years ago that included the words “twin study” in a post about alleged governmental crimes. Layla messaged the user and received an almost instantaneous response. SWITCH TO ENCRYPTED, the user wrote, and prompted her to download and open another app.

What Layla learned about the twin study: It had lasted only one year, the year she was born. It applied solely to second-generation babies and their first-generation immigrant parents. Contact between twins and parental units was strictly forbidden. Its stated purpose was to measure differences between a baby who lived only among people who looked like them and an identical baby who lived only among people who did not look like them; the researchers hypothesized significant detriment to those in the latter group, which could be used to underpin proposed limits on immigration. It ended during an election-year recession, in which congressional budget cuts had shut down the R&D division of the DHS in a flurry of nondisclosure agreements and paper shredding.

Layla didn’t ask how the message-board user knew all this information, though they had written we in several key places, which led her to suspect an involvement that could not be directly spoken about. All of it seemed more than plausible. She felt she’d been rapidly progressing through the stages of grief for her lost twin—first denial, then anger at her parents for keeping this from her, for not having gone looking. She understood, though, that they would have been actively prevented from searching, in addition to lacking the means to do so. But nothing was stopping Layla from pulling at this thread years later. Everyone has forgotten, wrote the user, though you should still be careful.

She remembered a news article she’d read weeks earlier, about a man in coastal Tunisia who held funerals for migrants who’d washed ashore there, having died at sea en route to Europe. Smugglers or the water had long ago stripped away any identification the bodies might have carried. The cemetery graves he dug were meticulously marked, but not with names. Layla understood instinctively the man’s impulse, how he was burying ghosts as a means of bringing bodies back to life.

Layla was relieved to know no shadowy official figures had been monitoring her childhood. If they had, they’d have seen that her experiences were more of the death-by-a-thousand-cuts than the mortal-flesh-wound variety. When playmates wrinkled their noses upon entering her house, saying it smelled like curry, or when she was teased for worshipping many-armed gods or cows, she died a little. When she begged her parents to go to prom with a floppy-haired white date, her parents died a little. That same boy—and many others—had admired her like an exotic flower, an orchid to place in full view on a windowsill until it wilted, not to be replaced. The bloom never lasted. She became preternaturally aware of her surroundings, of the expressions on faces unlike hers the moment before they shifted. The unsettled face—whether it remained open, or fearful, or lustful, or eager, or closed—became the truth by which she managed living.

It was easier than Layla expected to find her twin. Shayla had an extensive social-media presence that bore an eerie resemblance to Layla’s. Both women wore their hair long and curly, and favored minimalist, androgynous clothes. Shayla appeared to have graduated from a master’s program in the same year as Layla (though in what, Layla couldn’t discern) and was now working some sort of job in New Delhi that provided enough discretionary income for her to attend frequent happy hours with a rotating cast of girlfriends. The only difference Layla noticed was that her own feed prominently featured images of her parents, whom she visited in Ohio whenever she felt up to the drive from Chicago. She posted pictures of her mother’s dosas and pickles, of family gatherings where she dressed in jewel-toned silk saris. Layla scrolled back years but couldn’t find a single photo of Shayla with anyone over the age of thirty, not even a flashback baby picture, not a distant relative, nothing.

She tried to manage her expectations for Shayla’s response, particularly because even broaching the subject of their origins felt like the opening to an email scam or an internet hoax. She prepared to be ignored. After making contact, though, Layla realized they had both shared the same feelings of incompleteness. Like a part of me had dislodged itself and landed somewhere else, Shayla wrote. There was no need to convince Shayla of anything; she was already primed to believe.

Being an only child, Layla had no idea what it was like to have a sister. She hadn’t known it was possible to have a confidant who was both your peer and your blood, who remained attached to you despite time and distance. Layla talked to no one on the phone except (begrudgingly) her own parents. But she could spend hours chatting with Shayla, sometimes just leaving the phone on the ground on speaker as they watched the same movie, alternating between Bollywood and Hollywood rom-coms, giggling at each other’s reactions.

The prospect of a meeting came up in no time at all. Layla couldn’t remember who first raised it. They discussed meeting somewhere in the middle, in Europe or the Emirates. But Shayla was eager to see the United States, much more so than Layla was to visit India. Shayla applied for her visa and asked a travel agent to hold a plane ticket that would arrive just after Christmas. I’m excited to see snow, she wrote, undeterred by Layla’s warnings about the Chicago winter.

When Layla told her parents about the plan, they didn’t look surprised. You’ve always been so determined, her mother said, but the way she sighed when she said it didn’t make it sound like a compliment.

The question of Shayla’s childhood was resolved matter-of-factly and without hesitation when Layla asked. Shayla had been raised in a group home outside Delhi, with other twins who did not know they were twins. Each of the children had a room with a bed and hot meals three times a day. Still, they often fought over the last scrap of chapati and slept in each other’s rooms, needing the white noise of another person’s breathing to fall and stay asleep. They were supervised and taught by a woman whom they called only Miss, though there were other women, never named and rarely seen, who stayed at the home overnight when Miss left in the late evening.

Miss kept her hair in a long, tight braid and wore the same navy-blue sari every day, like it was a uniform. The only indication of her age came from the widening swath of gray that surrounded the severe center part in her hair. Though she was stern-faced, all of the children knew her frown lines were quick to dissolve and reappear around her mouth as smile dimples.

Miss was merciless in her encouragement, particularly when the children were ostracized by outside peers because of their lack of lineage or turned down for opportunities because of their hazy provenance. At some point she had written You are no different from anyone else on the chalkboard, and no one had ever erased it.

One day, when Shayla was seventeen, Miss did not appear at breakfast for the first time in the children’s collective memory. A blond white man in a black suit stood before them instead. In an American accent, he said he’d been sent by his embassy to tell them Miss had been hit by a car while walking back alone to her home the night before. The driver had been drunk, and Miss had been killed instantly. The man handed out envelopes to each of the children. Inside, Shayla found a fat stack of rupees, which the man said Miss had generously left to them. Sorry for your loss, he said, before being whisked into his waiting SUV. Shayla fingered the worn notes, looked at Gandhi’s familiar grandfatherly face in three-quarter profile. It was the first time she had ever contemplated what money couldn’t buy.

Though Layla’s family was Hindu, they were also reluctant capitalists and easily susceptible to FOMO, so they celebrated Christmas every year. The habit began early in Layla’s life, when her parents grew sick of hearing their daughter list out in exhaustive detail the presents her classmates had received, not asking for anything, just telling. Later they grew to enjoy the twinkling lights, the smell of fresh pine in the living room, the fact that society dictated they spend this particular day together and that doing so made them feel like they belonged. More importantly, it made them look like they belonged. If Layla’s parents noticed that the lights on her balcony this year were extensive enough to simulate daylight, or that the wreath on her door was the size of a monster-truck tire, she was grateful they made no comment about it.

Layla’s family abided by a strict no-news rule any time they got together. The drumbeat underlying recent developments was already soundtracking their thoughts, enough to drive them mad without having to also speak of it to each other. They spoke, instead, of Shayla, of what they thought she would be like in person. They unwrapped token gifts to each other—new paperbacks, new albums by aging, once-beloved rock stars, old sweaters in new colors. The next day, Layla drove them to O’Hare to meet Shayla’s flight, which was due to arrive midafternoon.

Walking up to the terminal from the parking lot, Layla could already spot something amiss in the standard airport tableau. There was a roiling crowd around the entrance being filtered into several separate queues. Uniformed military personnel stood motionless at regular intervals holding rifles by their sides, their eyes scanning back and forth like Kit-Cat Klocks. A few protesters held signs aloft that read No Ban, No Wall, jockeying for visibility against the counterprotesters’ One Country Under One Christian God placards. As they approached the crowd, a police officer directed them to a far line that contained only people of color. Some were grumbling, some were speaking to lawyers congregated at the periphery, some were crying, but most were looking at their passports in their hands, simply trying to achieve the purpose they’d come for, which was to get inside. This was the tactic Layla took, though she felt inviting fingers of rage applying pressure at her temples.

At the door, she and her parents were each thoroughly frisked, and the officer looked back and forth between their American passports and their faces so many times Layla worried that their documents—duly procured from the appropriate government office—were fake. Born here? the officer asked. Me, said Layla, my parents were naturalized. Wait, he said. We need copies. He went to a makeshift plywood guard booth a hundred feet away and came back with their passports, returning them without making eye contact, already looking ahead to the next person.

Inside, the scene was even more chaotic. A generalized din filled the air, composed of sobs and chants and jeers and cries of frustration. All pretense of efficiency, of an invisible conveyer belt funneling passengers to the necessary embarkation points, had been discarded. People huddled in any patch of free floor space, looking stricken or panicked. Layla and her parents let the crowd carry them to a television below an arrivals board that was showing CNN on mute. She watched the ticker cycle through the same headline at least five times before understanding its implication. An amended travel ban had come into force that morning, barring entry to foreign nationals from an extended list of security-risk countries that also happened to have significant non-Christian populations. Layla drove her parents back to her apartment in silence. The next evening, she received a message from Shayla, who had spent the majority of the preceding forty-eight hours in the clouds. She had arrived to Chicago, had her visa stamped VOID, and been sent back to Delhi on the next returning flight. Shayla was disappointed but remained hopeful that Layla could come visit her instead.

The Drumbeat:

It’s our right, as a sovereign nation / to choose immigrants that we think are the likeliest

to thrive and flourish and love us / it’s not unconstitutional

keeping people out / they’re giving you people that they don’t want

they would like to have open borders / where anybody in the world can just flow in

including from the Middle East / from anybody / anywhere

they can just flow into our country / we want to be strong on the border / otherwise

you’ll have millions of people coming up / not thousands / but millions

overtaking the country / and we’re not letting that happen

if you’re weak / if you’re really, really, pathetically weak / the country is going to be

overrun with millions of people / we get them

we release them / we get them again / we bring them out

these aren’t people / they’re animals / come on in, anybody

just come on in / not anymore / we’re liberating our towns

we’re throwing them out so fast / they never got thrown out of anything like this

The ban stuck despite scattered outrage, protests, and legal challenges. Layla dreamt of a hallway in which every doorway was an unlidded eye. While at work she accidentally left her purse in the women’s bathroom and was greeted midday by a security guard who halfheartedly interrogated her. The colleague who reported her was unabashed: If you see something, say something. Layla began ordering her necessities online to avoid social interactions, growing sick of analyzing every stretch of sidewalk and questioning the motives of each sweet-faced person who glanced at her while talking on the phone.

In early spring, a new executive order was signed. Layla received a frantic phone call from her mother in the middle of the night after ICE agents kicked down her parents’ door with deportation orders. Her mother kept babbling about the splinters in her hands from cleaning up the mess. Three unpaid parking tickets from her parents’ grad-school days in Columbus had been unearthed, the accrued amount now sufficient to enable the government to strip them of their citizenship. Layla was not allowed to visit or contact her parents once they were placed in federal custody. She had no money for a lawyer, and her social-media feed was already wall-to-wall GoFundMe appeals. She tasked Shayla with finding and caring for her parents when they arrived in India. In the meantime, she would determine how much of her own life required her to continue living in the place where she was born, and whether she could stomach the same oceans of distance her parents had endured.

After a few weeks, Layla’s parents popped up on Shayla’s feed, usually with an added veil of tiredness dragging down their features but once in a while with a budding smile. Seeing the three of them together, without her, was like watching herself be cut out of a family photo. She felt guilty about it, but she sometimes screened her parents’ calls because speaking to them about the same unchanged uncertainties had become too wrenching to bear.

The loss remained an open wound; Layla had no possible method of closure. She could not summon the resources to reverse the deportation, nor discern in the morass of .gov webpages an actual process for doing so. She spoke to no one about what had happened, not wanting to risk discovering where her friends’ and coworkers’ true sympathies lay now that the country’s hierarchy of belonging—and her family’s revocable status within it—had been made plain. Layla recognized that, on some level, everyone on the inside looks at people kicked out or excluded and thinks: They must have deserved that, there must have been a good reason. For most of the people she knew, the government was and always had been a benevolent entity to whom good reasons were readily imputed.

What were her own reasons in the face of that? Only a desire to go to the temple with her mother to receive divine blessings for a new year marked on none of their calendars; a wish to sit with her father for his patient guidance on filling out the same federal and state tax forms, year after year; a hankering to debate with her parents about the current political landscape in India, though they all knew next to nothing about it; or a craving to show up on her parents’ doorstep for no reason at all, for nothing more than to breathe air warmed by the same blood as hers.

Layla had never before thought it necessary to collect proof that she deserved her family, that she deserved to hold within her homes and histories that reached beyond the borders of her citizenship. While aimlessly flicking through television channels, passing the time outside of work sequestered in her apartment, she often heard talking heads screaming anchor baby or chain migration, as if the words were themselves a fully articulated argument. Layla, freshly untethered, understood now why these terms were so attractive to policymakers seeking to solve a problem they’d invented. They turned families into a contingent rather than necessary unit for certain citizens, made parents a ship to be sailed away, made a child a link to be severed.

In late summer, a new executive order was signed. The agents came to Layla’s door in the morning while she was getting ready for work, still wearing a flower-patterned bathrobe. She was driven to a holding facility in a recommissioned yellow school bus, her bare thighs sticking to the plastic seat. A jumpsuit was presented to her upon arrival. Her information was gathered and processed, and she was asked to provide a list of references who could vouch for her. She was told she would be released as soon as it was confirmed she presented no possible security risk. She was led into a large, open space that looked like an airplane hangar, filled with unmade twin beds. The room contained young people of many different ages and races, switching seamlessly from a mix of foreign languages to unaccented American English. All of them felt immediately familiar to her.

A week passed before Layla and five others made a run for it. The second-generation facility was sparsely guarded, particularly in the predawn hours, when at least one guard could reliably be found asleep. The issue after that was where to go. Nowhere they could run felt far enough away. She could tell from road signs that they were in northwest Indiana, not too far from her apartment in Chicago, though she knew her residence and place of work would be the first locations checked. All she had on her were the identification papers issued to her at the facility, to be worn on her body at all times.

After hours of running, she and the other escapees collapsed in a grassy meadow behind a dilapidated barn that had been freshly painted with an American flag. Layla wondered if the unexpressed purpose of the twin study had all along been to return immigrants to replacement children, because the problem of her own birth on this soil could not be solved. She’d thought she would have her entire life to undergo the necessary self- and other-self-reconciliations, but that project, it seemed, could both start and finish without her.

The escapees lay on their backs to look at the sky and discovered they each had different names for the same constellations, remnants of half-remembered bedtime stories whispered to them by parents. In school, she’d learned that the three bright stars above her were a fearsome hunter’s belt. For her parents, they were an arrow still lodged in the belly of an overreaching god.

By her toes she noticed a thick curl of smoke, registered the sharp smell of burning. One by one, the escapees knelt and added the sheaf of papers from their pockets to the growing pile. The fire began licking the surrounding grass, and they hurried to cross a stream at the edge of the field as the flames spread. From there, they watched a series of lights turn on in the nearest house—first upstairs, then downstairs—and a shadow-puppet show performed against the drawn white curtains. None of the escapees had a phone to call in the inferno, but Layla could already hear sirens wailing in the distance, responding to someone else’s alarm.

Author’s note: The italicized section of this piece is composed entirely of comments made by Donald J. Trump during public appearances or speeches between 2016 and 2018.