Nonfiction

Things I Lost in the Move

by Megan Burbank

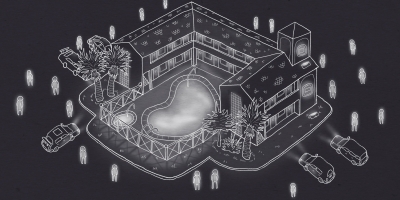

Notice of Proposed Land Use Action

The neighborhood is full of holes. One gapes behind the gutted awning of what used to be Bill’s Off Broadway, filling up fast with glass and concrete, another skinny condo tower in progress. Another hole replaced the parking lot where we kept our car when we first moved back, where I almost ran over a homeless man because he was sleeping in our spot. He leapt up just in time, gave me a terrified look, and ran away, draped in a dirty blanket that had once been cream-colored, trailing dried leaves like orange ermine. Another Notice of Proposed Land Use Action went up in front of the only house on our block just last week, a one-story bungalow squeezed between brick apartment buildings. Washington State has a three percent vacancy rate. Our apartment has no doors between its rooms.

Hello Kitty Pepper Spray

When I said I was heading home from Late Bar, my friend lent me her switchblade. This was when I was in grad school in Chicago. There had been shootings in our neighborhood, and reports of a serial rapist. Ashley showed me how to flick the blade out. I practiced unhooking the blade, triggering the release mechanism with my thumb. I did it over and over again until it felt natural, until it felt good. At home, I practiced in the mirror. I was wearing a tank top and jeans. I felt like Buffy the Vampire Slayer. I made a fierce face. I flicked the knife open. I flicked it open again. Don’t you fucking mess with me, I said. I flicked the knife open again and again until those words felt true.

Shortly after, I ordered a pale pink canister of pepper spray off Amazon. It was adorable, and would leave a magenta residue on anyone I sprayed it at.

The hot pink menace.

A Bumper Sticker

In what used to be a primarily Scandinavian neighborhood down the hill from where I grew up: Ballard welcomes our new condo overlords.

Psychogeography

According to Guy Debord: “People can see nothing around them that is not their own image; everything speaks to them of themselves. Their very landscape is animated. Obstacles were everywhere. And they were all interrelated, maintaining a unified reign of poverty.”

The Only Bad Thing That Actually Happened

Before we moved in together, when Trevor lived on the South Side, I once rode my bike down Kedzie Boulevard through Humboldt Park, past Garfield Park, through Douglas Park, past the most dangerous intersection in Chicago. I felt tremendously stupid, but I also felt separate from everything else, an outside observer flying past, untouchable, like a ghost. We spent the night watching Mullholland Drive with his roommates while a summer storm cast odd light outside and stray white kittens crawled along the porch railing. The family that lived upstairs never went to bed and appeared on the porch intermittently, the adults smoking cigarettes, the kids looking into our open windows. I fell asleep picturing David Lynch’s mud-faced monster behind the diner. In the morning, I biked back to Logan Square, where a friend of mine told me not to bike through Garfield Park anymore, unless I was prepared to be knocked from my ghost-post with a baseball bat. It was 90 degrees out and would be all week. Freeze-your-pillow-before-bed weather. When Trevor and his roommates moved out a month later, they left behind a bike and a computer monitor that didn’t fit the in U-Haul. They locked the front door behind them. When they came back to retrieve the bike and the monitor, they’d both been stolen, pulled through an open window immediately after they’d driven away.

Resist Psychic Death

At work, no one comes in until 9:30, but we all stay late. Most of us have cried in staff meetings. We are told and we tell ourselves that we should be grateful that we get to work for one of the good guys, that we must resist burnout. That we do this work to help the Representative change the world, not to earn money, that that’s our trade-off. That someone’s friend is a teacher now because she burnt out so soon. She became a teacher. She gave up ghostwriting the Representative’s speeches and is now a teacher. The first time I heard this story, I was a new hire. I believed it. A year later, I no longer do. I haven’t traveled in a year. I hardly make rent. I’m only publishing occasionally in online journals, and I haven’t finished reading a book in months. My introvert tendencies in my extroverted line of work have left me bitter and tired. We have begun holding meetings in which to schedule other meetings. Burnout, it seems, is just a stigma-laden word for the logical reaction to poor working conditions. I wonder if this was why Kathleen Hanna became a stripper.

Psychogeography

According to Gerald Locklin: “i envy those / who live in two places. there is always the anticipation / of the change, the chance that what is wrong / is the result of where you are.”

Everyday Violence

Before Seattle and Chicago, I spent a year in Paris, one of the loneliest of my life. I signed my first-ever lease on what was called a studio but was actually a closet-sized space partitioned—probably illegally—out of what was already a small-enough apartment. This, by an old man who charged exorbitant rent to any foreign visa-holder unlucky enough to not realize that they were getting swindled.

My new home was in what I affectionately called “the bad part of Paris,” because it seemed there was really no such thing. While I was walking to the subway one evening, a drunk, leering man on the street shouted at me. He was a red-faced French cliché, though no less terrifying for being one. I didn’t acknowledge him, as was my custom, though my entire body tensed at his sloppy overtures. My silence angered him. He shouted again, this time indignant, instructing me to speak to him. I kept walking. He was tremendously scary. I had dinner plans. I thought I was far enough away, but then the beer can hit the back of my head. It was almost full, a solid projectile. Beer spilled into my hair and down my back. I started to cry the way you do when you realize that someone who doesn’t know anything about you wants to hurt you. “That’s right,” he said. “Run!” I do not remember if he laughed. I remember that I was already running.

At Emily’s apartment that night, we ate cheap noodles and sprayed her Dior Cherie perfume on my wool jacket. I couldn’t afford to get it dry-cleaned. I tried to like my neighborhood after that, to be at home in my comically awful apartment. But I would never feel safe there again and I knew it. At the end of the month, I broke my lease and moved out. I never got back my deposit.

Psychogeography

Guy Debord again: “The study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.”

Ex Libris

In Chicago, Anne and I would meet up at the Logan Square farmers’ market late every Sunday morning. She was a thirty-five-year-old fiction writer who up until that year had worked as a pharmacist and lived in Brooklyn, and I was a twenty-three-year-old poet whose proudest accomplishment had been an unpaid internship at an alt-weekly, but we became friends within the first few weeks of grad school. At the farmers’ market, we bought expensive granola and talked about art, because that was our job. We had caught separate ends of the riot-grrrl movement, in DC and Seattle, and we shared Dodie Bellamy’s Barf Manifesto and books by Eileen Myles and Maggie Nelson and Kate Zambreno like bootleg tapes. We drank wine and wrote silently in each other’s apartments. We imagined writing our poems and stories with a kind of sharpness, a bodily immediacy like vomiting. We met Rebekah, who’d grown up in a cult, been married and divorced, written soul-sucking copy for money, and now wrote the most fucked-up stories we’d ever read. When I moved away from Chicago after grad school, I still had Anne’s The Importance of Being Iceland, and Rebekah still had my Heroines.

This is Not My Beautiful House

In the television show Clarissa Explains It All, Melissa Joan Hart’s spunky, crazily-dressed Clarissa is best friends with her next-door neighbor Sam. She actually keeps a ladder in front of her window so that Sam can drop in whenever he feels like it. In the television show Dawson’s Creek, young Dawson has a similar arrangement, so his best friend Joey can come by for coed sleepovers spent in thrall to Steven Spielberg whenever she wants. Growing up, I watched TV shows in the summer when it was too hot to go outside, the blinds in our living room pulled down against the sun and the summer-whitened square of the front yard. I longed to have neighbors I knew so well I would consider it unremarkable to discover them in my home, uninvited, unannounced, no switchblade needed. But TV small towns are a heartwarming fiction. I grew up in a city. We never knew our neighbors.

Psychogeography

I don’t carry pepper spray anymore. Last week, an acquaintance wrote on Twitter that she doesn’t either, “because i refuse to live in fear.” I don’t know if the latter is possible. Fear is not a decision, it’s an involuntary function of our reptilian brains. But while the fight or flight instinct cannot be logic-bludgeoned into submission, perhaps the real choice is whether or not we build a home inside of it.

There Goes the Neighborhood

In Seattle, signs go up protesting the Microsoft Connector, the newly built or almost-built condos, the rents that go up every year. We drive everywhere. The transit system isn’t broken; it never got built. Freeway cloverleafs only look beautiful from above. We wear raincoats and miss our commutes on the El. Holes continue to replace buildings. Don’t fall in, I joke, whenever we walk past our neighborhood’s newest addition. When people talk about Chicago here, it’s with distance, even caution. The air smells cleaner and the mountains feel right, but I miss the electricity.