Small Plates

an excerpt from

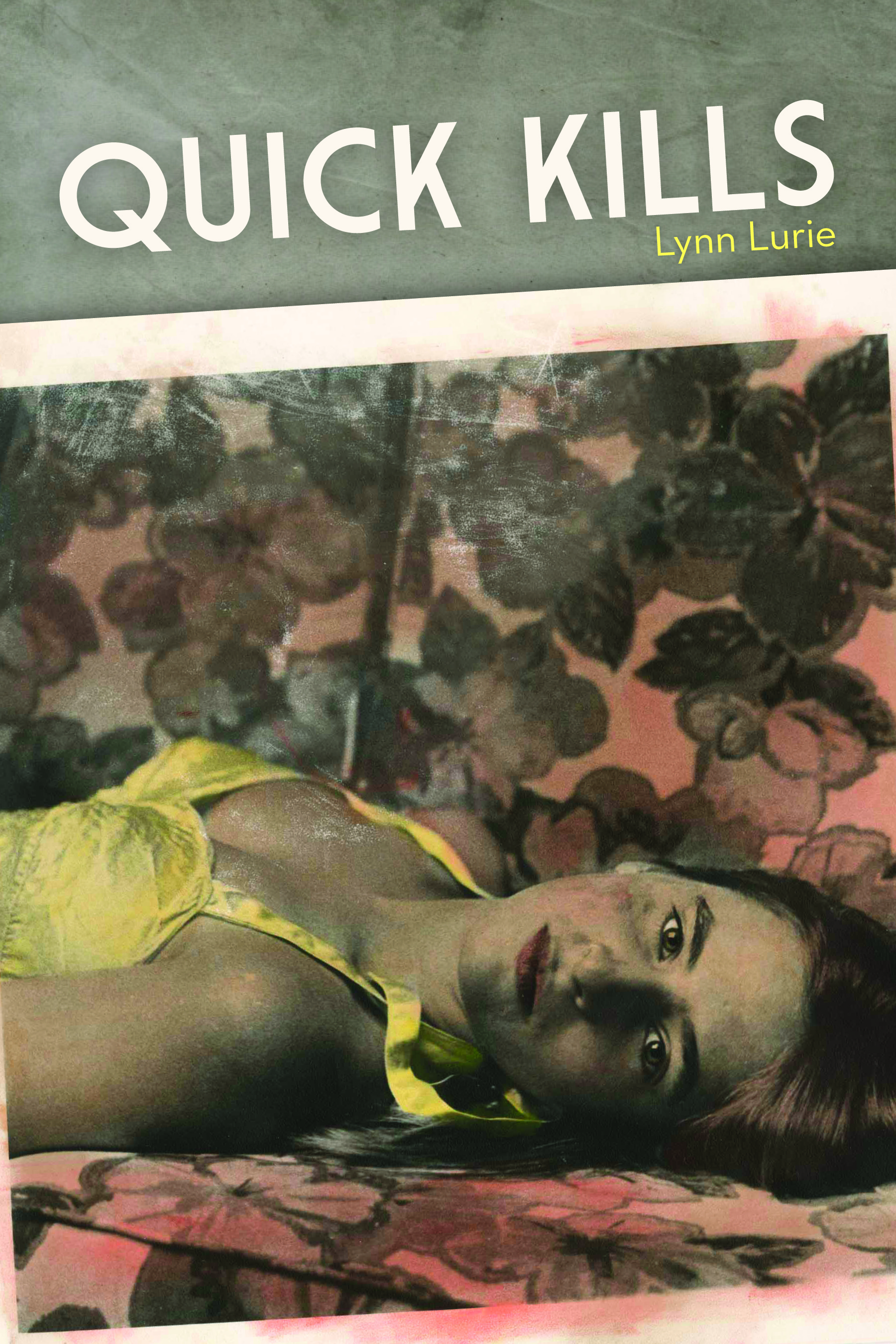

Quick Kills

by Lynn Lurie

Editor’s Note

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to be haunted by a book. What it means to have a writer’s words shadow my daily routines, only to disappear and then creep up on me when I least expect. To be haunted by a book is to carry around language and turns of phrase, images and voice, to think of these things suddenly and gravitate towards them because their power is fierce and inescapable. These things clutch at me because they remind me of everything I love about the reading experience, and what’s more, everything I love about writing. About its tangible, emotional ties to our internal and external worlds, about its ability to extend beyond. These things remind me of why I immerse myself in stories, time and time again; of why, until I’m dead, I will most likely never stop. A haunting, in this way, is welcome. A book is the best kind of ghost.

Lynn Lurie’s Quick Kills is a novel that has trailed me for the past few weeks. I cannot shake its presence, and I have no desire to. Just published by Etruscan Press (and brought to my attention by publicist and literary friend Lauren Cerand), Quick Kills is the story of Leslie, the daughter of a hunter, whose grave home life is all but matched by her relationship with a local—and much older—photographer. To give away much more would be doing any potential reader a disservice. Though the book itself is slim, at just over 100 pages, Lurie’s prose is a thicket of mystery and beauty. In Leslie, Lurie gives us the most captivating of voices, and as a writer, she gifts us with gorgeous, spare sentences and intricate details that feel at once familiar and wholly new.

As you might imagine, Quick Kills is not an easy read; there’s an insidiousness and tension tattooed in the novel’s skin. But I am never interested in what’s easy. I am interested in what wants to live inside of me. When I say it’s with great difficulty that I chose the following excerpt, it’s because this book is more than a ghost. Quick Kills is that rare breed that wants to climb into your body and settle in your bones. It wants to possess you. Let it.

— Rebecca Rubenstein, Editor-in-Chief

Mother’s father wakes most nights after we have gone to sleep, calling out in Russian and in Yiddish. The infection in the bones of his legs that tormented him as a child is back. I pray for him each night before I go to sleep even though I have never done this before. When he begs Mother to kill him to end his pain, I am sure this is what it means to go mad. I escape his screaming by crawling between the mattress and the box spring.

One afternoon I come home from school and Papa and all his clothes are gone. We do not visit him in the hospital. Mother says children are not allowed, and when I ask if I can call him on the phone, she says it isn’t possible.

Jake laughs. Maybe the mud reminds him of a cartoon he has seen. Roadrunner will fall from the cliff scorched by gunpowder and reappear as if nothing at all happened. No one else laughs. The caskets keep coming, emptying from the helicopter’s hull. We watch silently until Jake interrupts, asking the names of the planes, badgering Father to explain how they are able to land in the jungle without a runway.

Mother’s father is gone all winter and well into spring. After school Helen sits at the kitchen table and looks out the glass doors to our backyard that borders the neighbors. She says, I am teaching myself to draw snow using a white crayon from Papa’s box of colors. The hardest part is the ice because it is between a liquid and a solid, on the edge of change and there are no twins.

Her flakes are not ordinary, not like the cutouts we made in first grade, more like the lace of a dress. When she’s done, she covers it with a piece of tissue paper to protect it from smudging and asks Mother to bring it to Papa in the hospital. Father lifts the tissue to look at the picture. He tells Helen she is talented. I want to be that too, but Helen refuses to show me what she knows. When she isn’t at the table, I try to trace her snowflakes using my finger, the way they curl and dead-end and start up again, one merging into the other. But when I take the crayon and try to reproduce what I just traced, my snow looks nothing like hers.

I begin sleepwalking. They tell me I resist being taken back to bed, repeating in a monotone, I am going to the hospital to visit Papa. When I wake in the morning I am not in my pajamas but fully dressed, my blouse and skirt crumpled. Worse though, I have no memory of what happened and I am afraid I might be going mad.

At the entrance to the school cafeteria is a table with individual cartons of milk and a dish for money. It’s an honors system, three cents. I steal mine, pretending to pay. Some days I take back two pennies as if I left a nickel. The women in blue hairnets sell blue and pink iced cupcakes from behind the counter and each week I save the change that isn’t mine until I have ten cents for one. After I finish eating, I squish the brown lunch bag into a ball and toss it into the garbage. But I see the creases in Papa’s face and I am unable to leave it, even though it is covered in the mustard from the sandwich below and the milk I tossed in after.

I begin to store the creased bags and leftover food in my locker. Many times a day I ask to go to the bathroom or to the nurse’s office so I can make sure that all the many Papas in my locker are okay. I count the bags, keeping track.