Small Plates

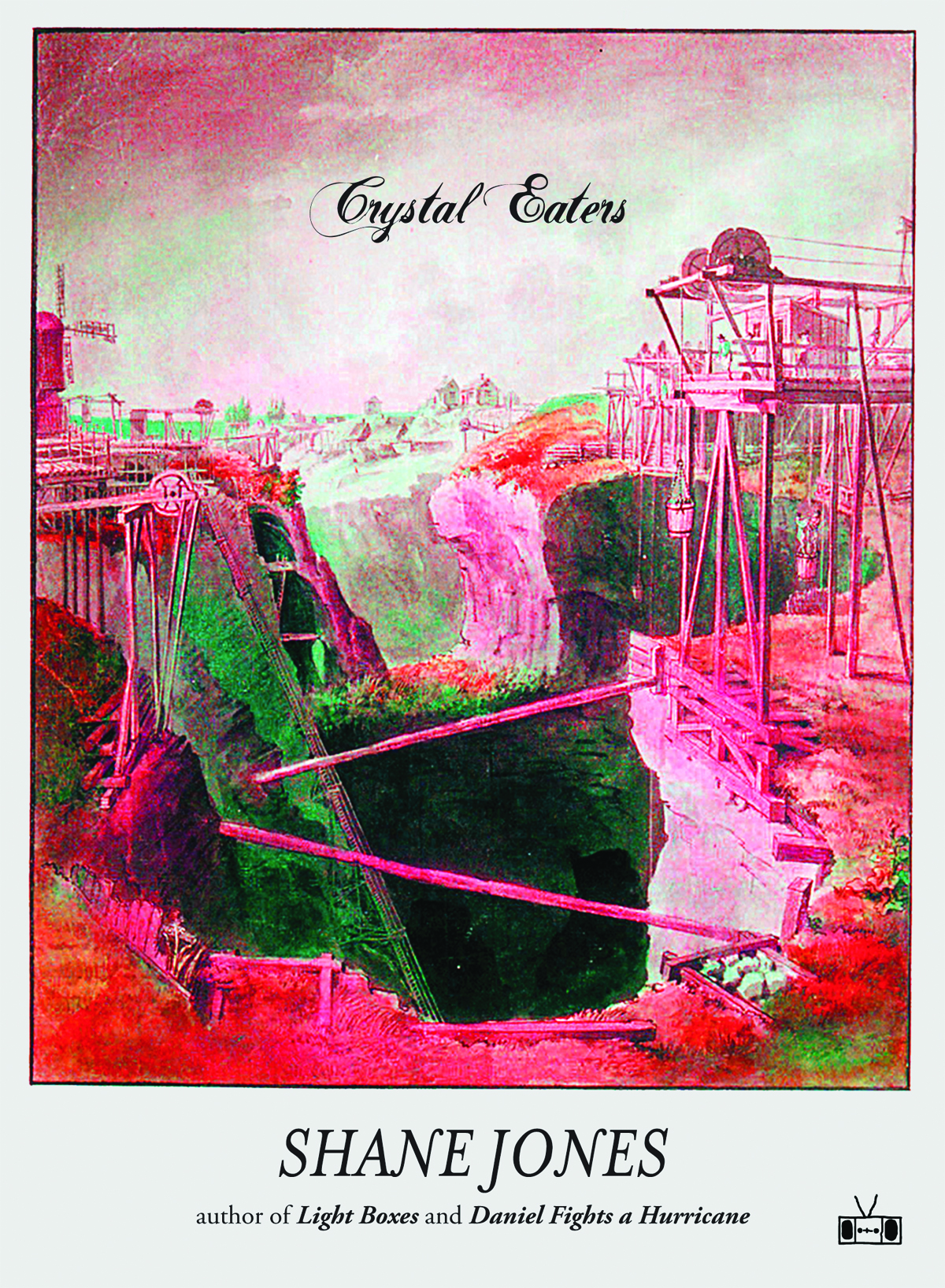

an excerpt from

Crystal Eaters

by Shane Jones

Editor’s Note

A few months ago, I began to hear murmurings of a novel called Crystal Eaters. Both HTMLGiant and The Rumpus gave the book (and its author, Shane Jones) glowing reviews, and then last month, Largehearted Boy featured Jones as part of its Book Notes series. Shortly following this, Laura van den Berg sat down with Jones for The Paris Review Daily, and their conversation was so fantastic and engaging, that if it had been the only thing I read about the book, I would have found myself sold on the spot.

Not that I needed to be “sold.” There are a few presses whose catalogues are so impressive, who so consistently publish daring and beautiful and sharp work, that I’ll often pick up a copy of their latest without reading a lick of press because I know what I’m holding in my hands will deliver. Two Dollar Radio is one such press. Almost ten years old now, Two Dollar Radio is an indie responsible for trumpeting luminous voices like Karolina Waclawiak, D. Foy, Grace Krilanovich, Joshua Mohr, and countless others, and I’m glad Jones has joined the press’s exciting, growing repertoire.

Before Crystal Eaters, I was sadly unfamiliar with Jones’s writing, but now, I’m thankful for the discovery. The novel is a poignant look at a village that subsists on crystals, and follows one family’s trajectory as it grapples with illness, secrets, and the outside threat of modernity. It’s dreamlike and devastating, with language that affixes itself to your bones and won’t let go, even long after you’ve finished. I can’t recommend it more highly.

— Rebecca Rubenstein, Editor-in-Chief

Mom has okay days and bad. At her worst, she stays in bed where she coughs crystals into the spitting cloth (Chapter 2, Death Movement, Book 8). Her number skims a green lake, dives, and tadpole-swims away from her. During her okay days Mom sits in the triangle of sunlight entering her window and warms her face for hours. At the dinner table she acts in a way that doesn’t turn Remy’s head in the opposite direction. But most days are bad. Under the covers at night she traces with her finger the sharpness of her hipbones and imagines a man fitting both hands around her as if she were a clay pot, lifting her up, and drinking what liquid is left.

She moves the screwdriver over the black crystal trying to peel it apart.

The family has broken apart over the years in a honeycomb hexagon of ways. That’s how she sees it — a solid shape but with separate pieces inside. She remembers the night in the mine, the men who lunged after her. They were dressed like mine workers. She didn’t speak to anyone about what had happened. The distance between herself and her husband is an endless black field, their bodies as shadows inside the black field moving away from each other, neither able to see the other. She didn’t want to be touched after it happened and Dad’s hand-on-hip move in the kitchen was viciously swatted away. She told herself, or was it Dad, she could push the experience away, and with time, destroy it.

She places the piece, which is the size of a clipped toenail, under her tongue. It’s sharp and with any movement will sink in. She sits on the floor in the sunlight triangle. She considers trying for the Horses Hologram again, and in the thought, doesn’t realize she’s chewing the crystal, breaking it into specks, and swallowing.

It’s a good amount of black crystal to take. When a hot flash blankets her body she inspects her arms because they feel swollen. There’s the tadpole-swimming-away-from-her feeling again but this time it’s pleasant and warm. Her body is at first underwater, then exploding out of the water and into the sun. Heat, a hard ball of it, rolls up from her stomach and clogs her throat. She screams, laughs, sees herself running the circumference of the earth. She swallows and the lump in her throat flattens. Mom thinks she’s added and with one finger she taps her chest and counts to fifty. She smiles into the sun with her eyes open, blinding, not caring. On thirteen pieces of paper she writes

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

I’m not sick anymore.

and throws them into the air before she feels an insatiable need to move and be alive. She walks from her room and through the hallway with beige paint peeling and family portraits with green crystal-studded frames melting. It’s impossible to lose her balance, she feels so good, so she skips on one foot for several steps, laughing, until walking again, hands tracing waves on both walls. She stops at his room in one big jump.

Dad sits on the bed, pillows propped up behind him, his legs extended. He wears a pair of white underwear with blue trim. His body is sprouted with black hair, his skin tan and cracked. He is sad, quiet, tired. From the uncovered ceiling light his body glistens. She asks why things are so difficult. He sighs dramatically. Mom isn’t acting like Mom, asking him more questions, brimming with energy. What can she do so Remy doesn’t grow up to be like her Brother? Is she bad? Tell her she’s not. Tell her things like bathing her children in the kitchen sink, and breast-feeding them every hour, and walking them for miles inside their home to sleep, and comforting them through endless cries, and trimming their nails while they squirm, and massaging little constipated bellies, and walking slanted from exhaustion, bruising her arms on doorways, and not bathing for a week, and eating all meals over the kitchen sink, eyes and mind always on her babies, everything for her babies, never putting herself first, tell her it meant something.