Fiction

Alfa Whiskey Echo

by Carlea Holl-Jensen

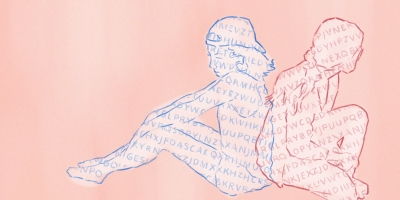

We used to talk in code. You were Alfa, I was Whiskey. In homeroom, during study hall, we used Caesar and Atbash, simple ciphers. We taught ourselves Morse code and the NATO spelling alphabet, repeating the letters back and forth to one another until we’d learned them by heart: • —, — • • •, — • — •, like that. On the telephone we would communicate by tapping our fingertips against the receivers. Be careful, someone might be listening. Dit-dah, dit-dah-dah.

In my dream of you last night, I dreamed in code. After years of radio silence, you appeared to me, the very picture of a femme fatale, and said, DLTBB, QXXRQSH. There was a Wehrmacht Enigma in front of me, like a typewriter in a wooden box, its lettered lampboard ready to illuminate your meaning, but I just sat there. I didn’t move. ZJTJHD, you said. A good spy would have tried one rotor setting after another until she found the right starting position, but I never touched a single key. Why didn’t I? Was it that I didn’t know how to decipher your message, or that I didn’t want to?

Your parents got divorced the summer before we started high school, and they sent you to sleepaway camp while their lawyers negotiated.

You mailed me letters every week, and I spent hours decoding them, the only part of you I had. Uryyb, Juvfxrl, they all began. I traced my fingertips along the curves of your words while my other hand sketched out the translation, A for N, B for O. Your pencil dug deep grooves into the paper, an indelible mark.

Your letters were full of the kinds of adventures I imagined Nancy Drew might have had at camp, up until some valuable heirloom went missing—hiking, canoeing, making out with boys in the woods after curfew. You told me, using ROT13, about Evan, the boy from New York who’d unhooked your bra behind the boathouse and put his brusque hands on your breasts. Ur’f phgr, ohg ur’f fb obevat, you complained, and I couldn’t help laughing.

I had nothing to tell you, except what I invented.

When the divorce was final, your father spent a muggy afternoon loading his possessions into a big white U-Haul. From our front windows, I watched him carry box after box into the truck, his shirt dark with sweat as he strained under their weight. I wondered why he didn’t have anyone to help him, why no one in the neighborhood had volunteered. Your brothers had also been sent away for the summer, though I never knew to where.

Your mother kept the house, and for the rest of July and August there was always a small crowd of trucks—carpenters, painters—parked out front, always the sound of buzzing and hammering coming from inside. I peered through our curtains, speculating, making up stories to report back to you.

Plumber’s van parked out front third day in a row, I wrote. Possibly CIA surveillance? I felt this was preferable to the real news I could have given you from home. Otherwise, I would’ve had to tell you that I spent most of my time reading what little the public library had on code breaking and that watching reruns of Get Smart and The Avengers without you next to me on the couch wasn’t nearly as much fun.

You didn’t get back from camp until right before school started. I was counting down the last week of vacation, imagining myself as an operative waiting for a connect. Every day I thought, Surely now, surely today. I watched for the light of the lamp in your bedroom window, our signal you were free to talk. It wasn’t until I was waiting for the bus that first morning that you materialized behind me, closing your left hand around my right. I was so startled that I almost jerked out of your grip.

Hello, Whiskey, your fingers said against my palm, as if you’d never left.

You wore your skirt rolled up at the waistband, your legs long and powerful and very tan. It hadn’t been that long ago that we’d played the game of convincing strangers we were sisters, but now I felt pale and round in comparison.

I missed you, I said.

You were smiling, though you were looking past me at the dense green trees that lined our street, never meeting my eye. Of course you did.

You told me I couldn’t come over after school because your mother wasn’t done decorating yet. I said I didn’t care what the house looked like, but you said your mother did care, so it didn’t matter what I thought.

You’d always preferred my house, anyway. At yours, you were on constant alert for your brothers, whom I saw around the neighborhood but never really spoke to. I only knew them as the clatter of their book bags by your front door, lean figures at the other end of the hall at school. You always made me leave as soon as they came home. I asked once if it was because you were embarrassed of me, and you laughed, a harsh, crashing sort of sound, and said, It’s just that I want to keep you to myself. I was flattered, at least enough that I didn’t ask again.

We spent the afternoons at my house instead. We did our homework at the kitchen table and then lay on the floor watching old spy movies. We practiced that Bond girl sangfroid, trying to master the art of stubbing out a cigarette and heartlessly tossing our hair. The cigarettes were your mother’s menthols, filched from her purse in ones and twos. The beauty of this strategy, you told me, was that your mother smoked in secret, thought you didn’t know, and so, you said, could never confront you about stealing them. You always offered me one, even though you knew I wouldn’t accept. Someone else might have given me a hard time, but you just shrugged and said, “Well, if you ever change your mind…” You smoked on our back patio, looking back at me through the sliding glass door. The door tended to stick from the outside and when you wanted to be let back in, you would tap little messages on the glass to get my attention, • • • — — — • • • and — — • — — • — — — • • • — — • — —. Sometimes I just stood on my side of the door and shook my head, pretending I wasn’t going to let you in. As your tapping got more and more plaintive, it would become harder and harder for me to keep a straight face, until we both dissolved into laughter, leaning against the glass to keep from falling down.

“Do you ever hear from that boy from camp?” We were sitting on the patio, enjoying one of the last warm days of the season. Out of the corner of my eye, you were edged in gold light.

“What boy?” you said.

“You know, the one who—” I hesitated, as if I didn’t remember his name. “Evan?”

You stretched out long in the chair, your dark hair spilling down over your shoulders. “Definitely not,” you said.

“How come?” I twisted around in my chair so I could see you better.

“What about you?” You tipped your head to look at me, eyebrows high. “Any summer hookups you’re waiting to hear from?”

“Just Alan Turing,” I said, and you laughed. “Did you know that he died from eating a poisoned apple?”

For a long time, you didn’t say anything. Then: “Evan was an idiot, anyway.”

This was something that hadn’t been in your letters. “Why do you say that?”

You dragged your arms up over your head and arched your back, like you’d just woken up from a long sleep. There were scratches on the underside of your arm, right where the sleeve of your t-shirt rode up, red lines. I watched as they were exposed, centimeter by centimeter, then turned my head before you could catch me staring. “Who poisoned him?” you asked after a while.

“Who?” I imagined Evan, his lips blue from cyanide.

“Alan Turing.”

“Oh. Nobody. He poisoned himself.”

You let out a long, slow breath from between your teeth and I felt, somehow, I had disappointed you.

While I was reading about Virginia Hall and Krystyna Skarbek, you’d discovered that Coach Geller was more likely to excuse you from gym if you flirted with him. You used hall passes from Mr. Alvarez to take forty-minute trips to the restroom and collected tardy excuse slips from the student office aid whose eyes, when he spoke to you, were never on your face. It became a sort of game to you, seeing how much you could get away with.

People started noticing. Boys you didn’t even know would ask you out, and girls who used to invite us to their birthday parties in middle school started spreading rumors about you and calling you a slut behind your back. I was embarrassed, angry, wanted someone to tell them to stop, but you said not to listen to them. You were the one who cared less. For you, it was an art. You said you had made yourself immune to sentiment.

No one asked me out. I wouldn’t have said yes, anyway. I didn’t daydream about seducing someone for nuclear launch codes. You, on the other hand, wanted to sell state secrets, keep a cyanide capsule in your tooth. You wondered what it would be like to slit a man’s throat.

I loved you for that. I loved your ruthlessness, your indifference. Nobody else matters but us, you told me once. You were sleeping over that night—we must have been in fifth or sixth grade—and we lay chest-to-chest in my little white bed because you said your sleeping bag was too hot. The lights were out, and in the dark your eyes looked big and empty and bright.

Nobody else matters but us.

I asked you once if you remembered saying that. You said you didn’t.

“I’m not doing my algebra homework anymore,” you announced one day on the way home from school.

“How come?”

It was raining, a cold rain, promising winter. You were hunched under the hood of your raincoat, scowling down at the water pouring into your shoes.

“I thought you liked Mr. Miller,” I prompted, when you didn’t answer.

“That class is such a joke,” you said with a sneer. “He doesn’t even look at our work, just grades the answers from the book. I checked.”

“What do you mean, you checked?”

“I did all the work, then put down the wrong answers, and he didn’t even notice. You can pass the class based on the midterm and final, anyway, so the homework doesn’t even count.”

Not long after that, you started ditching algebra altogether. I knew you spent the period smoking behind the science building because I could smell the menthol on you when you turned up at lunch. In the bathroom, you would touch up your eyeliner, examining every angle of your reflection through slitted eyelids.

I thought of you as Mata Hari. I imagined you facing the firing squad without fear.

I was wrong, though, to think you weren’t afraid of anything. It was just that the things that scared you were different from what frightened me.

When we were out together, at the diner, or getting coffee, you couldn’t bear to have your back to the window and would make me switch seats with you, even switch tables sometimes. You watched the street more than you looked at me, your expression tense and guarded. I couldn’t tell what it was you were looking for, but you never seemed to find it.

You said the mothers at school were always watching you, judging you. You were convinced Mr. Miller’s wife drove by your house sometimes in the middle of the night, her headlights dark. You got in a screaming match with the clerk at the drugstore once because she said something to you under her breath, but you wouldn’t ever tell me what it was you heard her say.

Another time, we were walking home from school when your brothers went by on their bikes. One of them stood up on the pedals of his bike and shouted, “Hey, sluts!” while the other tossed a lit match at you.

The flame went out in the air but the matchstick burned your cheek, right below your eye.

“Are you gonna let us fuck your friend?” your oldest brother asked you.

“We’ll even let you watch,” said the younger one. “How about that?”

I waited for you to yell at them, to cut them down to size, but you just stood there, stock-still on the pavement, tracking their movements without ever looking directly at them.

“Hey,” your oldest brother said, turning to me, “let’s see your pussy. I bet it’s real sweet.”

I tried to catch your eye, but you wouldn’t look at me. You didn’t even move until they’d rounded the corner, laughing, and disappeared from sight.

I put my hand on yours, wanting to send you some private message, but you wrenched your arm away from me. We walked all the way back to my house in silence.

Winter was mild, I remember, one big, long nothing. You spent most of the break at my house, eating every meal with me and my parents, sleeping crammed into my twin bed with me. My father accepted your presence without question, even sitting in on our film noir marathon for a little while, but my mother started to lose patience after the first week.

“This is supposed to be a time for family,” she said one day while you were taking a shower. “She must have some other friends who want to spend time with her.”

“Maybe she just likes me better than her other friends.” My mother and I never argued, at least never outright, and I felt bold, reckless talking back to her. I felt this was something you would have said in my place—and from the sour look on her face, my mother clearly agreed.

“I hope she knows she’s not coming with us to Grandma and Grandpa’s for Christmas.”

For a moment, I wished desperately that I could take you with me. I wished my parents could go to my grandparents’ without me and leave us behind on our own. I wanted it to be the two of us only, no one else in the world. I remember thinking, Maybe then— But I could never get any further than that, just, Maybe then—

In the end, of course, you spent the holidays with your family. We exchanged gifts before I left: a switchblade comb and a tube of Siren Red lipstick for you, a biography of Alan Turing I’d already read for me.

That spring, we went to the mall to pick out bathing suits. My mother wanted to come with us. She didn’t like you much in those days. She tried not to show it, but her mouth began to press a tight line whenever I brought up your name. “We’ll be fine,” I told her, rolling my eyes, and eventually she agreed to let me go.

You chose a black bikini with a low-slung belt that made you look like Ursula Andress just emerged from the sea. I imagined a small pistol or a knife strapped to your hip. You smiled at yourself in the fitting-room mirror, your teeth very sharp and white, and then you turned to smile at me.

“Come on, try something,” you said. You held out a cherry red one-piece with a padded bra.

I shrugged and said, “There’s nothing to fill it out.” I still didn’t have any breasts to speak of, and my stomach wasn’t flat enough for a two-piece.

“Just try it,” you said. I felt, for a moment, like your prisoner—like we might not leave the humid fitting room stall if I didn’t comply. It was always easier to give in to you. I peeled off my shirt and slid my shorts down my legs. You unhooked the bathing suit from its hanger and stood there watching as I squirmed into it. In my flat triangle bra and panties, I looked like I was playing dress-up in some grown woman’s clothes. I didn’t want to look in the mirror, much less look you in the eye.

“See, it looks stupid.” I started to drag the straps from my shoulders, but you stopped me. Your hands were tight on my shoulders as you turned me around to face the mirror. You raked your hand into my hair and shook it loose.

“There!” you said, as if you’d discovered me, as if, before that, I wasn’t there. Your smile reflected sharp in the mirror. “You could kill in that.”

I couldn’t imagine myself the way you described me—as someone dangerous, someone mysterious. That was you, not me. I saw myself bent over a Typex at the GC&CS, not lounging around on sun-kissed beaches in lingerie. In the end, I decided I didn’t really need a new swimsuit, since the one from the year before still fit okay.

On the last day of school, some senior dumped a gallon of water on me as a prank, and you gave him a black eye. I’d never seen you move like that. It was like watching something inside you uncoil—something that had been waiting a long time to strike. There was relief, delight, blind rage in the snap of your arm. When I saw you later, standing outside the principal’s office, you smiled, a brilliant, fearless grin that frightened me.

You were grounded for two weeks, but you snuck out while your mom was at work. I was sure you’d get in even more trouble, but you told me not to worry.

We stayed in my room just in case. You braided my hair on my narrow bed. Your lean fingers carding through my hair made me want to close my eyes. “You didn’t have to do that.” I couldn’t make my voice go above a whisper. “I don’t want you to get in trouble because of me.”

Your hands tightened in my hair, and it almost hurt. “I don’t give a fuck,” you said. The fierceness of your voice made me want to turn around and look at you, but you held me fast.

I don’t give a fuck. Tension gathered between my shoulders and I was scared for you, though I couldn’t have said why. Nobody matters but us.

After your grounding ended, we spent almost every day at the outdoor swimming pool. You lay out tanning. I read. Neither of us did much swimming, me because I got earaches, you because you didn’t want to get your hair wet.

But mostly you came to the pool to be on display—for the boys from our speech class, for the lifeguards, for the college kids home for the summer, sometimes even for the fathers of neighborhood children, men I would see mowing their lawns in sweat-stained shirts in the late afternoons. They loomed over us poolside, trying to coax you into conversation. I could feel their shadows as cool lines across my legs.

Sometimes you let them buy you sodas or snacks from the vending machine. You made a game out of who wanted you most, what they would do to have you, but none of them won in the end.

Later, you would tell me about it, recounting every fumbling gesture, every stuttered compliment. You laughed at them, how eager they were to make themselves ridiculous for you.

The day after Fourth of July, you came over to show off a rash of tiny puncture marks on your arms and legs. Your brothers, you told me, held you down and stuck pins in you. You rolled down the waistband of your shorts to show me the bruises where their hands had pressed you to the floor.

I was horrified, nearly crying, but you were almost proud. “If I’m ever captured,” you said, “I’ll never break.”

For my birthday, my father had promised to take us to DC for an exhibit on women in espionage.

We picked you up early and drove into the city, along the slow curve of the Beltway, past the white and gold spires of the Mormon temple. As we crawled through morning gridlock, I watched the streets for Secret Service agents and unmarked vehicles with bulletproof glass. You leaned your head against the window and closed your eyes.

The museum had only just opened when we got there, and the marble corridors leading to the exhibit were all but empty. The space was so quiet I could hear our footsteps, each distinct—my father’s long, brisk gait, my slower step, your light, near-silent tread.

You stopped reading the explanatory plaques after the first five minutes, wandering instead from room to room, flirting lazily with the museum guards. One of them, the young one, had very white teeth. I worried you were mad at me.

In a glass display case, a dozen intercept sheets from Bletchley Park, marked by the delicate strokes of the analyst’s pencil. I started crying at the sight of them, thinking how precious that paper was, how tenderly it had been made to yield its secrets. I rubbed my fingers against my eyes, hoping nobody had seen.

That’s when I noticed you were gone.

After a little while, my father noticed, too, and when he asked me where you were, I could only shrug helplessly. “I think she went to the bathroom,” I said.

A minute passed, and then another.

On the wall, a map of dead drops in East Berlin.

I forced myself not to check my watch.

Making a circuit of the room, circling like a nervous hawk, my father said, “Do you want to go and check on her?”

The restrooms were marble and chrome, still clean that early in the day. You were not in any of the stalls.

Next to the restrooms was a door marked “Employees Only.” I thought about pushing it open, looking for you there. I thought about the straight line of the security guard’s shoulders in his uniform jacket. I thought about your hands on his back, clenching that dark fabric. I thought about his hand over your mouth, crushing your lips against your teeth, pressing your nose closed. I thought about the pinpricks flecking the bruises on your thighs.

My stomach started to churn. I thought about faking an illness, a dizzy spell or nausea. I wished I knew how to fall down without hurting myself. I wished I wasn’t afraid of hurting myself when I fell.

I lingered by the water fountains, taking tiny sips of ice-cold water that did not rinse the taste of bile from my mouth.

You turned up twenty minutes later carrying a bag from the gift shop. Your hair was mussed and I saw a red mark on the flesh of your shoulder before you pulled your shirt higher up around your neck.

“I was about to call your mother,” my father said.

“Sorry, Mr. C,” you said, smiling. “But I got you a present.” A pen with invisible ink.

For me, a book safe, styled to look like the collected stories of Sherlock Holmes. “Happy birthday,” you said, and for a moment I forgot how frightened I was, how sure I’d been that you hated me, that you were gone forever. “Are you done? Want to get ice cream after lunch?”

That wasn’t the only time you went missing.

I knew there were nights you didn’t sleep at home. Some of them, you spent with me. Other times, you’d tell your mother you were staying at my house and slip out once my parents had gone to bed. You would return before dawn, walking barefoot across our wet lawn, still wearing the same clothes you had on the day before. On those mornings, when you got into bed next to me, I could smell stale cigarettes, some stranger’s cologne. “Just ten minutes, I don’t want to go back yet,” you would tell me, your hair slippery on my pillow.

Toward the end of that summer, you told your mother you were going to see your aunt in Bethesda and didn’t come back for three days. Your aunt said she hadn’t seen you, that you’d never even mentioned you were coming. Then one afternoon the police showed up and walked you back to your front door.

Your mother more or less stopped letting you leave the house after that. You would call me on the phone, tapping out messages like a telegraph operator. • • • — — — • • •, • — — • • • • • • • • • — • — • — • — —. I listened with my eyes pressed closed, trying not to hear the stuttered rhythm of your breath. • • • — — — • • •.

The last time you came over to my house, you looked dangerous, wild. Rain was shattering down in torrents and you were drenched just in the time it took you to run across the street.

“I’m not going back there,” you told me. Your teeth were clenched with the cold, but when I tried to touch you, you flinched.

When I got up to turn the air-conditioning down, you grabbed my wrist and held me there. “Don’t make me go back.” Your voice was so rough you sounded almost like somebody else. I was afraid you were about to cry, and suddenly I wanted very badly to put some distance between us.

I twisted my arm out of your grip. “I’m just going to get you a towel,” I said.

In the hallway, I stood staring into the linen closet for a long time. I stood, listening to my breath catch in my chest and nothing else.

When I got back, your expression had gone flat, blank and still and determined. You didn’t say anything else to me about leaving.

We lay down on the bed, just like we used to do, our foreheads almost touching, hands clasped. I wanted to say something to you, to promise you would be all right, because that seemed like the sort of thing I should say, but all I could think of was our names, Alfa Whiskey Alfa Whiskey, over and over. Your hair was drying in fine curls around your face and you smelled like rainwater, like night air.

A few days later, you took fifty dollars from your mother’s purse and packed a bag and disappeared.

So many times since then, I’ve wondered why I didn’t ask you, why I didn’t say—something, anything at all.

Everyone had their theories about what had happened after you were gone. The police asked me if you’d been seeing anyone—maybe an older man? Maybe a teacher? Had you gotten into some kind of trouble? What about your home life? How did you and your brothers get on? Didn’t you ever confide in me? After all, weren’t we best friends?

How could I tell them that I never asked? Not, at least, the questions that really mattered. A good spy would have investigated. A good spy would have pushed for answers, even if they were answers she didn’t want to hear. But I never asked, and then it was too late.

For years after you left, I used to imagine breaking into your house. I could have used the spare key your mother kept by the back door. I knew where it was because you’d told me you used it to sneak back in on occasions when you’d stayed out past your curfew. I could have lifted up the loose tile along the rim of the flowerbed and let myself in. I could have crept up the stairs and into your bedroom, opened the jewelry boxes on your dresser, checked all your drawers for false bottoms.

But what would I have found there, in the end? What good would it have done? It wasn’t proof I needed.