Fiction

The Rose Apple Tree

by Rashi Rohatgi

She was hungry. Priti had felt sodden with pregnancy, waterlogged, and now she was immersed in the sea of motherhood, where fruits felt soggy and flavorless and cold to the touch. Lars’s expulsion from her body had seemed a discrete act, the bloody afterbirth stanched, but she still felt herself pulled inside out. Pierre’s mother, Hang, had taken to calling from France, demanding photographs. And there Lars would be, unexpectedly writhing on the tiny screen of Priti’s new phone, and there, too, beside it, constantly doubling, and she pushed as much food into her mouth as she could to make up for the lack of one satisfying crunch.

Since just before Holi, when Pierre had begun his paternity leave, the crib had been abandoned; Lars slept between them despite Pierre’s fretting about room to breathe, space to recover. On National Day—in May here, though the red, white, and blue of the Norwegian flags brought forth Priti’s own Fourth of July memories—Pierre had gone out in the evening. “Morten’s party,” he’d said—as though she could put names to the same four faces alternating across his myriad co-workers—and Priti had curved her arm into a shepherd’s crook to stop her log of a son from rolling off the bed, and then he had rolled, but toward her, and though by the time the sun took firm hold of its place in the sky Lars would be eleven months old, he’d found her breast again. And without Pierre’s wary witness, she’d given herself over to the feast.

When they’d arrived in this arctic hamlet, she’d carried the moon within her belly, and now it was everywhere and nowhere at once: on the floor of the living room, having taken her long-lashed eyes for itself, instead of in the sky where it was needed to do battle with the conquering sun. Soon there would be nothing else on the horizon, just the sea and the sky all one enveloping hue, no night to tell her changeling child to stop, stop, please, stop eating. Pierre loved to fill Lars’s freckle of a mouth; he tried to feed her, too, and she who had once screamed when he’d added sugar to her tea now bared her mouth quietly. In a week the moon would narrow itself to nothing and the dark would depart, and in a week Pierre would depart, his leave spent, so when he had the baby now, Priti tried to sleep, and felt her stomach curdle, and started to shake, but wouldn’t, absolutely wouldn’t, let Lars back on her breast until the allocated time. But she must. Most nights, she would stare into Lars’s coal-dark eyes and whisper the Gayatri mantra before cursing herself for encouraging the sun, hastening her abandonment.

The night before the start of the Ascension holiday, Pierre said he would be late, shopping alone: he wanted romaine, he wanted lamb, he wanted whole carts of foods Priti knew wouldn’t fill her. Pierre had moved here to work, and yet Priti couldn’t remember a time when she’d known him happier than those daily seconds at the door, casting his eyes about for his son. She was halfway through a stale tin of gingerbread, despite her ill will toward anything battered with flour, and as Lars pulled her closer with nails sharper than sharks’ teeth, she swallowed her anger and she swallowed as many cookies as it took to get a sharp hit of ginger on her tongue.

The next day, Hang called Pierre just as he was leaving. He came back in and took the phone off his ear to snap a picture, and so Priti could hear Hang’s comments on her hair and the jawline below. “Maman,” Pierre chided, but after he hung up he said, “Why don’t you two come out to the cabin with Morten and me today? You could take a turn swimming.”

God, she was starved.

“Priti?” He’d come and sat beside her on the floor, and he pulled Lars up from her arms and bounced him on his knee. It wasn’t clear who Lars looked like, his tiny black curls oily and ruffled. When Pierre secured the baby’s head in his right palm, he took his left and ran it up and down the top of her spine, bent his fingers round her neck, and when she shivered, he turned his face to her, and it was stone, and he said, “I think it’ll be good for us.”

“Vriksh,” she whispered to Lars, newly awake in his sling. “Dekho, munna, vriksh.” The woods here, on the far side of the mountain, were greener, wetter. When she’d attempted to pull her bathing suit on, her thighs had scoffed, so Priti’d strapped Lars in and begun to wander. Out here, the quiet felt deliberate but unimposing; it felt like she could join in without giving away anything, and so she let her narration die out. Without her words the air was wet and uninterrupted.

Though it was midday, the sun was too far above them to bestow anything but a soft gray light. As Priti looked at the slurping, pursed body atop hers, she thought of her dead mother, brows furrowed as she filed their taxes, and so Priti turned her mind to samsara, and then—for what else was there?—to her terrible hunger. The forest was full: of pine needles, and birds still too young to fly, and their mothers, to and fro, bearing worms. But there was nothing she could stuff into her mouth. She’d never killed a bird—she’d never eaten flesh. But there were ways of bloodletting with needles, weren’t there, that weren’t fatal? Blood, surely, tasted.

“Prim?” Morten’s voice was built for this place; his nickname for her wound through the shadows and landed at her feet, where she thought to ignore it. Lars loved Morten, she could tell: his rough red beard, his calves like—well, Lars wouldn’t know a watermelon. Calves like seven peeled, piled apples. She looked down, but he had fallen asleep again. His teeth slid forward to clench around the tips of her nipples; they’d draw blood if she didn’t wake him, just for one moment, but then the cry would draw the men in further. As he’d loaded Lars into Morten’s car seat this morning, Morten had said, in a cowboy’s drawl, “Nice to meet ya.” He’d spent a semester at a small college in Georgia and, de Tocqueville or not, he was here to tell her what he’d thought about it.

She wondered if there was another way out, one that would lead her to another side of the lake, maybe, but when she lifted her heel to move, the pain in her breast was sharp and restricting. She slid her nails under the two-toned lips that made her feel, more than anything else, that she existed in this village, in this body, and all she wanted in recompense and recognition was ghee and lime juice and crushed red pepper and garlic and corn that didn’t taste of the inside of a birdhouse. As the baby lunged for her other nipple she backed herself farther into the trees, slid on her heels, on and on until the leafy canopy brought a new darkness, a welcome stillness.

A gape, in fact. She looked down, and found Lars, mouth open, looking up. Not at her. Behind her. She squeezed him as she turned, but there was no one there. Just an old tree, dark and knotted, thick and full. She took a measured step toward it, and tried to see behind it without moving further. The animals she’d come across in this corner of the world weren’t small enough to hide behind a tree trunk, but then again, not everything in the woods was native to them. Another step. Still nothing. She looked down at Lars, but he was playing with her hair now, destroying her braid. She looked up, and there they were.

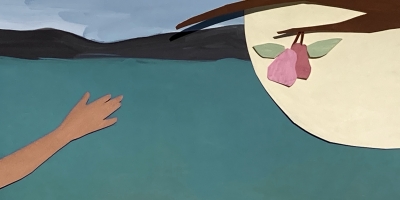

Part of her wanted to stop and take stock, just for a moment, of how beautiful they were: dark pink paisley drops, two together like doves. But she had been so very hungry, and she reached up with both hands and plucked the rose apples and held one to Lars’s mouth and let her teeth, her tongue, her throat cling to the juice of each bite, and soon hers was eaten and she looked down at her child and his was done, too, and she thought, for the first time, that perhaps her incomprehensibly clutching child might simply be thirsty.

They’d gotten lost, she lied—well, who knew if she’d have been able to find her way back through the woods?—and Morten whistled, impressed, told Pierre she was as resourceful as one of their girls, seeking out shoreline, and she forced her eyes not to roll when Pierre glowed in response, picked Lars up and spun him in a circle around the small grassy beach they’d found their way to.

“Come tomorrow,” said Morten as he dropped them off home, and she nodded. She saw Pierre’s sharp, quizzing glance, but didn’t respond.

That night she slept deeply, and when she woke, she saw the bed empty beside her, a small circle of milk pooled beneath her chest. She took a deep breath. For a moment she waited, and, then, still—she felt nothing. As she stripped her t-shirt and the sheets, she opened the window—almost two thousand years ago and a day, if sources Pierre held dear were to be believed, a singular avatar was raised into heaven. States changed. The breeze that entered the house was warm, and she went into the kitchen topless and saw Pierre and Lars stirring the eggs with a wooden spoon, and though Pierre’s eyes, when he looked up, went first to her pendulous gut and then next to her eyes, he smiled.

She made tea and watched Pierre fill a picnic basket. At the cabin, the men plunged into the lake—“Don’t go so far today, Prim,” Morten chided, chuckling—and though she wanted to run she kept her gait steady, for if she fell, there went Lars. In the sling, Lars drank from her, but slowly, as though she were fine china. In the trees, the baby birds were just slightly more awake, more alert, closer to sounding fully real.

This time, she paused—nay—stopped. “Mumma,” whispered Lars.

“Dekho, munna,” she whispered back. “Two more rose apples.”

If she waited too long, she was sure, they would dematerialize in front of her eyes. Rose apples had been hard to find even in the US. On visits to her parents’ home, she would sit with her father at the table, sometimes, as he peeled them—you didn’t need to peel them, but, with her non-native stomach, in India she peeled everything she couldn’t boil or fry—and diced them, slowly, carefully, a man unused to kitchen tasks. They’d only met Pierre once, but Papa’d placed his arm on her shoulder, and squeezed, as Pierre watched her mother make litti and shared, brightly, and so amiably, Hang’s recipe for bao. Here, she could place the entire fruit between Lars’s budding teeth, and as she bit into her own the taste was so clear she forgot her tears.

Morten was due elsewhere for the weekend, but as he bid them goodbye that evening, he handed Pierre the keys and told them to enjoy. Pierre narrated their plans to Lars as he put their lunch leftovers into a stew: a rented car, and wouldn’t he enjoy those olives they’d picked out together last week, and wouldn’t Lars enjoy eating them? With Papa and Maman, yes, of course, Doudou. He let Lars run his fingers under the open tap, and Lars’s cheeks quivered. “L’eau, l’eau!”

“He said my name today,” she said. “When we were walking.”

Pierre looked up. “That’s wonderful, Prit.”

She didn’t know what to say next, what she wanted to hear. She went to pack her things. Tomorrow, she vowed, she would sit with the tree day and sun-drenched night and then until day again and watch them grow. The trick, she thought, was to stay close.

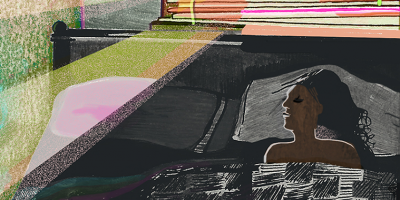

The water was as cold as promised, but Pierre and Lars stood on the shore, clapping for her, and so she went a step farther, a step deeper. Underneath her feet she felt the rough sand rise and fall; she felt the thick strips of seaweed twist around her ankles and then around her unclothed ass. Her second night of uninterrupted sleep made her relatively sure she wouldn’t slip. She considered turning around and then felt the tip of her braid take in water. She held her breath and bent her knees to bring the water over her nipples quickly, and then tilted her head back to let the water have all of her hair, let the sun shine its muted light straight down on all of her face.

By the time she rejoined them, Pierre and Lars had set up the red-checked blanket and poured two cups of cheap champagne and a milky bottle, set out the sour strawberries and the tasteless olives without garlic nestled where pits had once been, and a long crusty loaf that she no longer, she realized, felt drawn to. Pierre squeezed cheese out of the tube onto Lars’s tongue and looked at her and laughed. “I’m going to miss you both next week.”

She watched until she was sure Lars wouldn’t choke on the cheese and then she nodded.

“I’ll come back at lunchtime to see you,” he said.

She was shivering, and she drew her towel around her shoulders more tightly. “We’ll be fine.”

“I know,” he said, quickly.

Lars was squeezing the cheese paste onto the sand and she watched him do it.

“I’ve asked Morten to stop by every so often, see if you need help,” Pierre said.

“Mm-hmm,” she said, as neutrally as possible. “I need to go for a walk. You’ve got him?”

By the time the mother birds had finished feeding, the sun’s warmth had begun to falter, yet the tree hadn’t yielded, as she was beginning to anticipate, its two sweet fruits. Her breasts began to feel tight and her ribcage to lose hope of any nocturnal reunion with her spawn, for whom she knew she should rightfully save any rose apple, should it come. She hadn’t dressed, and so when her nipples began to leak she pressed her towel against them and wondered if Pierre had left Lars asleep and continued swimming. No, he wouldn’t.

She watched the bare branch on the strange tree remain bare, remain open, and waiting, and willing. Then she heard owls and she wondered if time had stopped, and then she heard her husband’s voice and her son’s tears and she blinked and by the time Lars leapt from his father’s arms to drain her, she could see two tiny pink fruits shining out of the corner of her eye.

On Monday, she awoke to an empty bed, but in the kitchen, Pierre was pacing, and when he saw her he nodded and headed straight for the door. “Morten is coming at nine,” he said. “Be dressed and ready.”

“Let’s go to the cabin,” she said when he arrived, not sure if she was misgendering the word for cabin.

“It’s chilly,” he said, shrugging.

If she mismanaged an attempt to be rid of him she might never find her way to the woods again. “I’ll grab a blanket,” she said.

More than anything else, Morten was white. He seemed to link his confidence to his physicality—he liked to joke about his Viking blood, though his beer belly would have seemed out of place at a raid—but he seemed unaware of where, exactly, his limbs ended, on which day of the week his beard went from scruffy to scraggly to downright rough. Whereas sometimes, when Pierre entered a room, Priti could swear Tchaikovsky’s Peter motif was playing somewhere, jolly, in the background, Morten’s perennial smile held no mischief, just blithe assurance. It rankled Priti that he thought he inspired anything in her but dread and a coincidental curiosity.

When they got to the cabin, he wouldn’t leave her alone. These are his woods, she tried to tell herself, but the words hung disparately in her mind; she couldn’t find meaning in it, that the fruit she needed belonged to this tree-sized, fish-fed oaf. They stumbled around on the beach until she spotted a crab, and while Lars was entranced, she mumbled something about the bathroom.

In the gloaming, she wanted to linger. Two fruits—still only two, and still perfectly ripe—hung just above her eyes, where she could reach them on her toes. They must be accustomed to this place. Or did each rose apple have to learn anew that despite the chill on their skin, this sharp needled corner was all they would ever get? She needed to hurry, she reminded herself, but instead she plucked slowly, gently, and held a rose apple in each palm, and warmed them there. She would save one, she decided, not just for Lars but for him to share with Pierre. Once Pierre tasted its flesh, he would remember who she’d been, once, neither flower nor fruit—a girl not requiring tending.

“Here you are.” Morten’s voice was quiet, and when she spun, she saw that he held Lars, asleep, in his arms, but now he bent low and placed the baby on a patch of moss between two stones. She tucked the fruits into her sling, took a step back so the tree held her upright as he approached. “You left your son with me.”

“He’s fine,” she said, but her heart paused until he nodded.

Morten’s arm lunged past her to take hold of the tree’s trunk, and her fruit-lined stomach nearly touched his. “What do you do when you’re out here by yourself, Prim? Do you think of what might have been?”

She blinked. His face was all she could see now, for his fiery beard filled up her peripheral vision in both directions. “Yes.”

“If you’d met me first?”

If this land had been mine, she amended, in silence. But everything around them was his and had always been.

“I know American girls,” he said. “I’ve known American girls.”

“Yes,” she said, and she wanted to close her eyes and get it over with, but if she lowered her eyelashes, they would brush his chin, and perhaps then Pierre would not believe her, afterward.

Morten laughed, his gut shaking, and Priti felt one rose apple fall from her as her jostled midsection resought its equilibrium. He took a step back and picked it up and bit into it, and grimaced. Throwing it behind him, he said, “You’re not an American girl. Come on. Let’s get the kid back before your husband gets home.”

She had lain flat on the living room floor and forced Lars to crawl atop her to suckle so that when Pierre opened the door, and hung his suit, and looked for Lars, the baby looked like a conquering wolf. She opened her eyes and sat up as he pulled Lars off of her.

“I got you a rose apple,” she said, pulling it out of her pocket. Lars paused his squealing to reach for it, and for a moment their hands fell on it together. Pierre had always had warm hands, and his son’s were even better. In the mild evening sunlight, they sat together on the floor and considered the fruit. “Do you remember these from when you were little?”

Beside Lars, the fruit looked small and lovely and perfect. Beside Pierre, Lars did, too.

“Better than what I found,” Pierre said, tilting his head back to his shopping bag, out of which were protruding carrots, a cabbage, and either a cucumber or a very sad squash, she couldn’t tell. He held the fruit up to Lars’s lips, and fixed his own around it, and Priti brought her face close to ready her teeth for a bite and marveled at how lovely the planes of his face were, this man who’d wrecked her. This rose apple, far from the tree, was the best one yet.