Fiction

Middle Kids

by Temim Fruchter

I auditioned for the Ronald J. Friedman Jewish High School Purim play just two weeks after I transferred there mid-sophomore year. I’d been told that, at Friedman, the Purim play was the event of the year. Everyone got involved. If you wanted to be someone at Friedman, kids said, you’d get involved, too. Even the least cool kids at Friedman seemed cooler than the kids I’d known at Beis Chana—a provincial all-girls school, religious and demure—so I wasn’t sure why they would be so fixated on what I’d always thought of as a silly children’s holiday.

Still, I auditioned. And, emboldened by my new-kid status and the pair of chain-link earrings I’d worn for the occasion, I killed my audition and was cast as Vashti. Vashti. I was still suspicious of the Purim play, but I did feel vindicated by the casting. The rabbis at Beis Chana had always spoken of Vashti in hushed and spitty tones. She represents taiva, they said, unbridled desire, and she wants unimaginable things. She defies the king, she is willful and promiscuous, she has no morals. She deserves the punishment she ultimately gets. She has a long tail like a horse, they said, making her less human and more animal. “Girls,” I remembered Rabbi Katzen saying, his fist pounding his desktop. “Vashti is a cautionary tale. Don’t be like Vashti.” I licked my lips remembering. If Rabbi Katzen hadn’t wanted me to be like Vashti, then by God, let me be like Vashti.

At our first rehearsal, we sat in a circle of folding chairs in the cafeteria as Yaron Ben-David, the student director, welcomed us in his smug student-director voice. “Everyone here knows some of the themes of Purim, right?” He paused as if waiting for an answer to his rhetorical question. “It’s a story of masks and unmasking, of changing fates. It’s a series of allegories, shifting loyalties, motives in disguise. It’s a hall of mirrors, at the end of which is some wisdom about the folly of human nature.” I wondered how many mirrors Yaron had practiced this speech in at his house last night before coming in here and acting like a big shot director, which everyone let him get away with because he was so golden and square-jawed.

As Yaron finished his soliloquy, I looked around the circle. Two months since I’d transferred here, and I was still getting the lay of the land. I’d worn a black leotard under a long black skirt—it felt theatrical, and besides, I’d been wearing a lot of strategic black in the hopes it would make me look edgy to my new schoolmates. Otherwise I looked generally plain and smiled flatly without my teeth, so my fate as a Friedman “middle kid” had been sealed pretty quickly. Middle as in not cool enough to belong, but definitely not cool enough to not belong.

Still, I’d become something of a pleasurable curiosity to the preppy set. I rotated pairs of dangly statement earrings that were too adult for me and that my aunt, a buyer at Bloomingdale’s, sent me monthly. I had recently taught myself how to braid my hair and then knot the braids into the kind of bun that made me feel graceful even though I had size-ten feet and the nail-bitten hands of a little boy. I had a lazy left eye that misbehaved when I was tired. In class, I doodled moodily, pictures of women that started with their cleavage and grew outward. I felt naked without my lipstick, which was, consistently and without exception, Wet ’n’ Wild #541A, a mud-dark shimmery brown that washed me out so much I resembled a ghost.

I wasn’t the only tenth-grade middle kid. We comprised a thin, nondescript social layer, and we spent much of our downtime in the slightly inferior of the two sophomore student lounges. There was Rochel, who’d been homeschooled for all of middle school and was fixated on musical theater; Abby, who was boring but had a nose piercing and jagged short hair, so people always assumed she had a freaky side she didn’t; Hillel, who was a nihilist and loved saying controversial things about not believing in God within earshot of rabbis; Lizzie and Noah, who were dating and always together, and who seemed mostly interested in Aeropostale, making out, and Pearl Jam; and Adira, who wore purple contacts and acted like she was in a death cult, but had eight devout siblings and a Chabad rabbi for a dad.

And me? I guess I was determined to keep my mouth shut about the reasons I’d transferred to Friedman to begin with. I didn’t miss Beis Chana, but I had the nagging sense that when I’d gotten kicked out, I’d lost something important. That in those dimly lit hallways, I’d begun to become someone truly powerful. To my new school, I’d brought with me the uneasy collection of feelings that had started possessing me there, that had driven me to do what I’d done. At Friedman, where I wasn’t yet sure who I was going to be, I’d done my best to contain these feelings so far. Only when I was securely inside my bedroom every night did the feelings threaten to grow so big and overpowering I worried that, one day soon, I wouldn’t be able to contain them any longer.

Yaron’s voice droned on, and I tried to listen, but it was hard to focus on anything or anyone but Mrs. Lubin, who, as it happened, sat directly across from me in the circle. Mrs. Lubin, who taught AP English to the juniors and seniors, was also the faculty advisor for the Friedman Purim play. If Mrs. Lubin was in a room, regardless of whether she was speaking, you could always feel her there. She was a little over six feet tall and broad-shouldered, with a rectangular face and a nose that resembled a fingerling potato. Built like a low-rise apartment building, she cast a shadow, her mouth and eyes often stretched downward. When she spoke, her voice came out slow and dark, gravel from a tipped shovel.

I was careful not to look at Mrs. Lubin directly. Kids at Friedman seemed both reverent and terrified of her. They even seemed afraid to gossip about her behind her back. Was there a Mr. Lubin? I didn’t dare ask. Everyone speculated liberally about the surly gym teacher and about the weaselly Talmud teacher who everyone was certain had been flirting with one of the seniors between classes, but gossip about Mrs. Lubin only happened minimally and in whispers. I dared myself to look up at her then, just for a second, and when I did, I saw that she was staring directly at me—unmistakably, and unblinking. Quickly, I looked down, shaken, but I could feel her eyes on me still.

Rochel had told me that one reason everyone was so fixated on the Purim play at Friedman was because it wasn’t the hokey kind like at other Jewish schools, where kids wore oversized robes and foil crowns and where the climax was some villain cackling across the stage with angry eyebrows and a triangular hat. At Friedman, it was sophisticated. Last year, the Purim play had been Shakespearean, she told me, and Purim-story-inspired plot or not, it sounded like a Romeo and Juliet knockoff to me. The year before, they’d acted out the story in the style of a punk Los Angeles fairy tale, all glittering lights and tall Doc Martens, Queen Esther taking the form of a Midwestern Jewish transplant who unexpectedly gets in with the unofficial mayor of everyone’s favorite skate park.

“This year, our theme is monsters,” said Yaron, proudly. “So the characters won’t be human characters. You’ll be costumed like monsters—monsters that are sort of like people, but also sort of like animals. Because Purim is about the strange and unexpected and even evil things humans are capable of. About how we’re all really monsters when you get down to it.”

“So, like Muppets or something?” said Gabriella Gershenson, who smelled like Clairol Herbal Essences and never raised her hand.

“No,” said Yaron, rolling his eyes. Rumor had it that Gabriella and Yaron had dated in the ninth grade until Gabriella dumped him for someone else. “Not like Muppets.”

“Like monsters,” said Mrs. Lubin. The bellow in her voice drew all the attention in the room to where she sat. How could someone’s presence be so commanding? I wondered. She was only an English teacher. “Yaron is right. We are all monsters in some way, aren’t we? The idea of a monster isn’t a cartoon or a punchline. Monstrosity is complicated. When you get home tonight…” Mrs. Lubin looked around the circle, stopping to fix her eyes for a moment again on mine. I made myself look back at her. Her eyes were small, and her mouth so large. What did she see in me? I was only sitting there. “…look it up in the dictionary, the word monster. See what you think then. See how it makes you feel.” It should have sounded like homework, a prompt, but coming out of Mrs. Lubin’s mouth, it sounded more like a threat.

As we scattered, the promise of finished scripts in our hands for the next rehearsal, I watched Mrs. Lubin leave. She shuffled a little as she walked, her frame filling the cafeteria doorway as she passed through it.

“Obviously, about monsters,” said Rochel, after rehearsal. She was playing Jewish Townsperson Number Two, who had zero lines, and she was clearly bitter about it. “That’s so obvious.”

“Well, yeah,” said Hillel. “Everyone’s basically a monster.”

Abby and I walked together to the back parking lot, where her father would pick us both up and drop me off at home.

I screwed up my courage. “What’s the deal with Mrs. Lubin? I mean, I know people are kind of scared of her, but, like, why?”

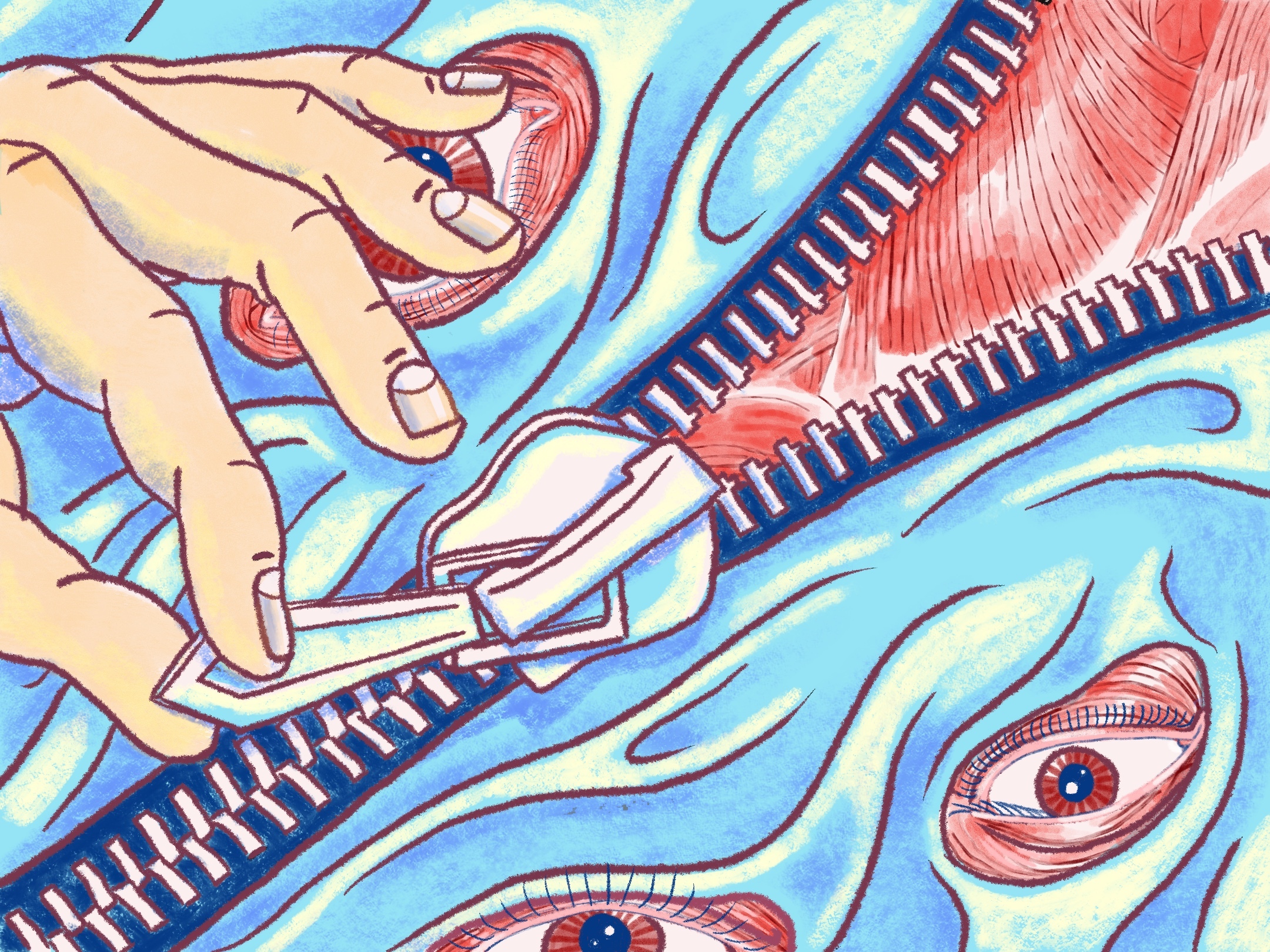

Abby looked shocked by my question. She turned to see if anyone was walking behind us and then stopped me by a cluster of lockers. “Look,” Abby whispered, shaking her head like someone tasked with delivering bad news. “She has a zipper.”

“A zipper?” I wondered if I’d heard her right, or if this was a figure of speech I wasn’t familiar with. My last school had been in a cultural Stone Age and hadn’t exactly prepared me to keep up with the expressions kids my age were using. “Like, on her body?”

“Yes,” said Abby. “A zipper. Like on a hoodie. But it’s on a person.”

“What is the zipper for?” Was this conversation actually happening? It felt lifted from a weird dream.

“No one knows,” Abby said. “Just that it’s there.”

Abby glanced around her again, and then, quickly and quietly, she elaborated. There were multiple accounts of the origin of this rumor, she said. One account went that four years prior, still recovering from the flu and slightly delirious, Mrs. Lubin was giving her students a lecture on some literary monster—Grendel? Abby wasn’t sure—and she mused, “He probably wished he could just unzip his skin.” She said it to the chalkboard and not to the students, and shortly thereafter, she left the classroom, ending class twenty minutes early, not to return to school for another two weeks. Another reported that one time, at a fancy school gala, Simon Minkowitz’s mother saw the zipper and several of its tracks peeking out over the top of the back of Mrs. Lubin’s gown, and told Simon’s father about it drunkenly in the kitchen that night; Simon had been awake and alarmed to overhear her gasping and giggling like a schoolgirl. A third, ancillary account was that a pair of bold ninth graders actually figured out where Mrs. Lubin lived, tricked their way into a ride to her neighborhood, and looked into her window. They saw her alone there—no Mr. Lubin in sight, tugging at her own back, at the zipper they were certain they’d seen there—and ran, afraid, when she started to turn around, almost certainly feeling their eyes on her.

I thought of the way Mrs. Lubin had stared at me from across the circle like I was someone to watch, and thought about what having a zipper might mean. I sort of liked how it sounded but speedily swallowed the thought—it didn’t seem like something I was supposed to like. I wanted to touch her, I thought suddenly, and was alarmed by the desire. I wondered whether the texture of her skin would be rough, like rubbing sharkskin in the wrong direction.

I came home from school distracted and especially hungry. We ate salad and mac and cheese, and I had seconds. My mother talked aggressively about the changing weather. My father gazed at me with the concerned expression he’d been wearing ever since I got kicked out of Beis Chana, like he wondered when something at my new school would go just as terribly awry. “Purim rehearsals are cool so far,” I said. I knew it would comfort them that I was not only getting involved in Friedman extracurriculars but actually enjoying them.

We had stopped talking explicitly about The Expulsion, mostly because it seemed like my parents had lectured and grounded me enough in the first two weeks and now weren’t sure what else to say. It was one thing to get kicked out of yeshiva for dealing drugs surreptitiously, hands trading little flat baggies for crumpled bills between the swish of long denim skirts in the religious school hallways, or to be gently asked to leave because someone decided you were a bad influence (see: Chaya Mordberg, who’d been caught one too many times explaining the diagrams in Seventeen magazine, and who wore ostentatious silver boots under her otherwise modest clothing on the daily). It was another thing entirely to do what I had done.

Of course, it had started with the money. It was a simple, straightforward theft: only two hundred dollars, and from one of the richest girls at school, Ilana Kleinbaum, whose neurosurgeon father frequently appeared on daytime talk shows and whose mother had an angry-looking nose job. She wouldn’t miss the money, and besides, it had been sticking out of her Calvin Klein backpack—all in tens, fanned out like playing cards—like it absolutely wanted to be taken.

By the time Ilana went to Rabbi Wechsler about the money, I’d begun to take so much more from so many other people. But no one at the school was wise to this yet.

“Why did you take Ilana’s money, Daniela?” Rabbi Wechsler had looked at me with these wounded Old World eyes, and I wondered why rabbis always had this way of seeming both intimidating and also afraid of you. Or of me, at least.

I had no idea how to explain to someone like Rabbi Wechsler that I didn’t know why. There were no words for why. I wanted it. I felt guilty, sort of, yes, but I mostly felt exhilarated, shot through with potential. Just days before taking the money, I’d picked up the phone, only to overhear my parents on a call with the school guidance counselor, who was in the middle of saying she thought I was struggling with self-esteem, a sense of self, and did I have a therapist? I’d put the receiver back on its hook, stunned. I knew that, lately, something had come over me, but I didn’t know what this something looked like to other people.

The money, though—it was better than any kind of therapy. When I got away with it, I knew I’d tapped into something true. I knew I would take again. And it wouldn’t just be money, either. The guidance counselor wasn’t wrong, after all: I’d begun to worry I was unexceptional, and nothing had ever felt so powerful as just noticing something I wanted and taking it. I wanted to see exactly what that much money would feel like in my hand.

It felt dry, mostly. A little cold. And thicker than I expected.

Upstairs, I looked up the word monster in the dictionary. An animal of strange or terrifying shape, it said. One unusually large for its kind; an animal or a plant of abnormal form or structure; or a threatening force. Finally, most strangely: one that is highly successful. I got into my bed and ran my hands all over the surfaces of my body. Some parts of me were dry and patchy, and some were unnervingly smooth. I thought of Mrs. Lubin, how through her thin black shirt I’d noticed the places her back rolled and folded, and I wondered now if the zipper was in one of those valleys. And of course: What would happen if she came unzipped?

As I drifted off to sleep, my skin tingling something fierce, I thought about how, in so many images of the Purim story, Vashti is drawn with a tail, just as my rabbis had always described her. The rabbis, after all, have always been afraid of a woman who goes off-script. But so what if Vashti really did have a tail? I thought, turning on my side. That meant people would have watched her, would have seen her as someone to fear. And maybe Vashti liked that.

On Thursday, at Purim rehearsal, Benjamin Krakowsky slid into the folding chair next to mine and asked in a stage whisper whether he could sit next to me.

I had a crush on no one at Friedman, but Benjamin had a crush on me. If nothing else, it was flattering, and after three years at an all-girls school, attention from a boy was novel. Benjamin, though, was licorice-thin and had those ceramic braces that were supposed to be invisible but actually just looked like gross plaque buildup. And, new as I was at school, it still kind of mattered who I chose to hang around with. So I tried a strike a balance between talking to Benjamin and not.

What I really wanted to do was point out that he was, in fact, already sitting. And besides, it made me feel weirdly angry that he asked my permission. Like, why couldn’t he just be decisive and sit? Instead, I said, “Sure.” I was trying to strike a balance here at Friedman. Loath as I sometimes was to admit it, I did badly want to belong, but I also knew that I couldn’t contain the burgeoning other self much longer. That staggering, covetous, jagged self, the one that felt large—too large—and that grew larger daily. The self that threatened to rear its head when I tried to repress it, knowing as I did that repressing it would be my only chance at making it through high school in one piece. I was determined to remain squarely a middle kid as I figured out this balance and who I would be in this brand-new place where no one had yet seen my tail.

Benjamin Krakowsky smiled shamelessly, and he sat.

Today would be our first day rehearsing with the script. The vain and foolish king Ahasuerus would wear peacock feathers. Esther would appear as some sort of queenly raccoon—diligent, resourceful. Mordechai would be an owl, watchful and over-serious. Haman, the villainous opportunist, would be a fusion of corporate executive and hyena. As Vashti, I was thrilled to hear I would appear as a wild horse. I imagined the tail of which my rabbis had spoken in warning and regretful tones, only now it was a shock of powerful horsehair, the thing that distinguished me, that would propel me into a gallop. The school band would be coming up with a kind of experimental score.

The read-through began, and quickly we arrived at the scene where the king asks Vashti to dance in front of all his party guests and Vashti says no.

“Not on my life,” I said, in my best guess at a Vashti voice. “I won’t degrade myself for you. I’ll dance when I want to, but not for you and your little friends. I am made for bigger things.”

“Louder,” said Mrs. Lubin. We all turned to face her. I wondered before I could stop myself whether she unzipped herself at night. I wondered if she was even bigger inside than she was out. “Daniela, I heard you at auditions. You were cast as Vashti for a reason.” I couldn’t read her expression when she said it, but I thought she looked a little bit proud. “Just that last line,” she said. “Give us more. Please.”

“Okay,” I said, my face hot with attention. I turned to Adam Shick, who was playing Ahasuerus. “I am made for bigger things!” I said.

“More,” said Mrs. Lubin.

I squeezed my eyes shut and pictured Ilana’s stack of bills. “I am made for bigger things!” I cried. It was like Mrs. Lubin and I were the only two people in the room.

“Again!”

“I AM MADE FOR BIGGER THINGS,” I roared, and I roared it at Mrs. Lubin directly. I’d forgotten about Adam. The whole room filled with me. I shivered with the power. “I AM MADE FOR BIGGER THINGS,” I screamed again, my voice cracking just as it hit the ceiling and cascaded back down to earth.

Mrs. Lubin nodded approvingly. “Good,” she said. “Very good.”

All that week, at home, I practiced appearing larger than I was. I read my lines over and over. I spat out the words no and never. When I needed to, I remembered how easy it was to take Ilana’s money directly from her bag. How powerful I felt after. And how, right after I got away with it, I wanted to try taking more. To see what or who else I could become. I took things from people, just little things. I took people’s learner’s permits and their wallets and checkbooks and made small decisions in their shoes. I took home other people’s tests, erasing their names at the top but proudly showing their grades to my parents. I got the names of people’s crushes out of their journals and started flirting with them myself. Once or twice, someone confided in me about a secret date—rarely, one of the girls from Beis Chana went out with a boy from Beis Avraham, the all-boys school—and I went on the date in their place. It was fun to take money, but the taking was more exciting when the stakes were a little higher. I felt most powerful when I was at least a little bit somebody else. Oddly enough, feeling like someone else made me feel more myself than anything else in the world.

When Monday’s rehearsal came back around, I was ready.

That day, we were practicing a banquet scene that doesn’t actually happen in the Purim story. It was “interpretive,” said Yaron. It was a sort of monster ball, he explained. Everyone was to parade onstage in their monster regalia, and then form a complicated kind of monster tableau, which would animate itself into a beastly dance when the music kicked in. Around the cafeteria, kids looked baffled and overwhelmed by the weird choreography Yaron was giving them. Ahasuerus’s feathers had just come in from costumes, and skinny little Adam was already complaining that they were too heavy. From the back of the room, Mrs. Lubin watched.

“Haman,” said Yaron. He liked to call us by our character names. “I want you to show a different side of yourself in this scene. Can you play this part worried, or conflicted?”

“Um, but isn’t Haman just evil?” Zack Schnitzer was good at playing a one-note villain. I wasn’t sure he’d be good at much else.

“Evil is complicated,” said Yaron, nodding sagely at his own commentary. From the back of the room, Mrs. Lubin nodded, too.

After rehearsal, the middle kids stood in the parking lot waiting for our rides.

“I actually think evil is uncomplicated,” said Adira. “It’s just so pure.”

“I don’t know,” said Lizzie. Noah stood behind her, his arms wrapped around her waist. “Isn’t everything always complicated?”

“Not everything,” said Adira. “Murder isn’t. Evil isn’t.”

“Spaghetti and meatballs isn’t,” said Rochel. Adira glared at her, purple-eyed.

“Love isn’t,” said Noah, and Lizzie smiled up at him.

“Get a room,” said Hillel. “You guys are gross.”

“Anger isn’t,” I said. I don’t know why I said it. I was thinking about the rabbis, about Vashti’s tail, about what I could have bought with Ilana’s two hundred dollars had I not been made to give it back.

“Anger isn’t,” repeated Adira in her deadpan, so that I couldn’t tell whether she was mocking or agreeing. “Yeah, I don’t know about that.”

After rehearsal that Thursday, Mrs. Lubin asked if I would follow her to her office. She wanted to see me. The whole walk from the cafeteria to her office door, I held my breath.

Contrary to what I might have imagined, Mrs. Lubin’s office looked like a normal English teacher office. Big bookshelf, desk piled with papers. On one wall, a large framed painting of a young boy playing the violin, and, at the edge of her desk, a little bowl of caramel-flavored Nips.

“So, Daniela,” said Mrs. Lubin, looking down at me, even from a seated position. It was way harder than I thought it would be to look at her directly, let alone to look for any kind of zipper. “How is your first year going?”

My mind revved. Oh no, I thought. Mrs. Lubin wants to talk.

“Um,” I said. “It’s going well so far, I think.”

“Hm,” said Mrs. Lubin. “I’m glad to hear that.” She folded her substantial clay hands together on her desk. I noticed a mug with light lipstick marks on it. Did Mrs. Lubin wear lipstick? If she did, I had certainly never noticed. “So, Daniela. I know you got into a bit of trouble at your other school.”

What? How did Mrs. Lubin know? And how much did she know? Just about the money, or about everything else? I panicked. I bit down hard, bit my tongue by accident. Ow. I said it out loud without meaning to. “How?” I didn’t quite finish the sentence. I didn’t need to.

“I know a lot of things, Daniela.”

I wondered, genuinely, what exactly Mrs. Lubin meant by this.

She looked at me kind of sideways. “You make a perfect Vashti,” she said. “And you have a new opportunity here. I just hope you’re smart enough to take it.”

“Okay,” I said. I wasn’t sure what opportunity Mrs. Lubin was talking about. I wondered if I was here because she understood that I, too, was a person who walked around with a dangerous, constant secret.

Then something happened: Mrs. Lubin stood up. She walked around to where I was sitting and knelt on the floor so that we were almost eye to eye. The room swayed. The proximity of my towering teacher was so unnerving I could barely sit still. I bit down hard in an effort to prevent my body from somehow going rogue.

“There’s something under your skin,” she said, and she said it so quietly I wasn’t sure if I’d heard her correctly.

“What?”

“There is something under your skin, Daniela, something extraordinary.”

I stared. I wasn’t sure what else to do. My mouth didn’t work.

“You must know this,” said Mrs. Lubin.

I shook my head. The small room was too warm, getting smaller.

“Well, you do know that it can’t stay under there forever,” she said, hushed. Then she stood up, walked back around to her large brown leather chair, sat down, and folded her hands on her desk again. The room shivered. The walls slurred, wobbly.

I bit my sore tongue again, on purpose, to make sure it was still there. I looked around the room to make sure I was still awake, alive. It was as though I had drifted into some otherworld. But no, it was still just me and Mrs. Lubin, the books and the lamp and the framed violin boy and the little bowl of candies no kid in their right mind would ever have the courage to take.

Is it true? About the zipper? I wanted to ask. How did it get there? Do you want it gone, or do you like it? Has anyone ever seen it? Could I?

“So,” said Mrs. Lubin, in her normal voice, from her normal chair, as though nothing out of the ordinary had happened. “I’ll see you at rehearsal next week?”

I nodded, robbed of speech.

After dinner, I went into my room and shut the door. There is something underneath your skin. I heard Mrs. Lubin’s soft and hypnotic growl over and over again, as I lay hopelessly awake, even as the hour grew later and later. I just hope you’re smart enough to take it. What did Mrs. Lubin know about me? What could she see that I couldn’t yet? I was embarrassed: I was at a school where I was still seen as harmless and unpunished, which should have freed me up to think about boys and outfits and new friends, but I could only think of Mrs. Lubin—her size, her scope, and her power over us all. Over me. I fell into a strained asleep that didn’t fully take me and that didn’t fully give me away, either.

By the time I got to rehearsal on Monday, I’d worked myself into a nervous frenzy. Yaron gave an impassioned and unnecessary lecture about the existential bleakness of the Purim story, and how we needed to bring all of our uncanniness to the stage. As he rattled on, I doodled nightmare images in my notebook: dark, curly ogres, pyres reaching for moody skies, tree-tall cats with teeth so sharp they resembled vampiric panthers. Maybe nervous wasn’t even the word. Something else coursed through me, coursed hard. I sat in my folding chair, shimmering and eager.

The other kids, it seemed, were getting restless.

“Aren’t we supposed to be, like, actually practicing?” Gabriella snapped her gum like kids did in the movies.

“Right,” said Zack. “Like, we already know this. Can we just act already?”

Even Benjamin Krakowsky looked bored.

The room dissipated into teenage antics as Yaron scowled in the middle of the circle.

Finally, in the corner of the room, Mrs. Lubin stood up. Her face looked grave in a way that seemed disproportionate to the occasion, as her expressions so often did. “You might be thinking this is only a Purim play,” she said. “But we’re tackling some very serious concepts here. I assumed that, in high school, you would be mature enough to pay attention, to really think about the implications of monstrosity. I’m not here to waste my time with children. You want to do a silly Purim play? You can transfer to another school.”

Everyone looked astonished by her outsize reaction, even Yaron.

“You can go,” said Mrs. Lubin. “We’ll continue on Wednesday.” I got up, mouth full of shame, and looked at Mrs. Lubin before I turned to go. Her eyes were different; there was something in them. Maybe hunger, or sadness, or exhaustion. It’s hard for me to say. But I do know for sure that it wasn’t the kind of look your students were ever supposed to see.

The next day, Mrs. Lubin was out of school, and the next day, and the day after that.

In the halls, the rumors spread fleetingly, only ever whispered. But a fly on the wall would have heard the word zipper from a nervous student’s mouth at least once an hour.

Mrs. Lubin didn’t return for two weeks.

For those two weeks, I started to feel things I couldn’t completely explain. First, I was hungry. Hungrier than usual. Where I’d normally eat seconds, I started eating thirds. I was insatiable.

Hungry, but also obsessed. Where was Mrs. Lubin? And what had she seen under my skin? How was that possible, for a person to have that kind of power? At night, in my room, with just my purple lamp on, I started to long for a zipper of my own, just so I could see too. So I could get underneath it, step out of myself, and, once I was out, see what residue or evidence I left behind. I want to unzip my skin, I thought, and then couldn’t unthink it. I want to unzip my skin, I thought, lying on my bed, on top of all the blankets, staring upward as I moved my hands down my sides, as though I could will the metal into me, as though I could make it so. It was my skin, after all. I began crying at unexpected times. In a quiet way, into my pillows, not even realizing what had overcome me until I noticed my body shaking.

At the beginning of tech week, Mrs. Lubin came back. No fanfare, just walked into the cafeteria in a boxy denim skirt and a yellow sweater and sat in the back of the room like usual. For the entire length of the run-through, I felt something like disappointment. A balloon with the air slowly seeping out.

The night of the Purim play, the Friedman auditorium’s lobby filled with adult strangers—mostly the parents of my classmates, I assumed. There was Adira, emerging from a clown car of little boys with curly payos, her mother in a dress that looked like a regal, plum-colored bathrobe. I remembered Adira saying something about how her father wouldn’t set foot in a coed school like Friedman, so her mother attended any school event that demanded the presence of a parent. Inside, Hillel stood with two alarmingly normal and well-adjusted-looking parents, who I watched approach my own for a friendly chat. Across the lobby, Hillel and I snickered at one another. Hillel didn’t believe in Purim or school plays, and was just playing a demonic extra who tromped across the stage periodically, as Yaron put it, for atmosphere.

I couldn’t wait to get into my costume, and was impatient to get to the dressing room, but I’d lost track of Adira, who I knew I’d need to help me get my false eyelashes on. I was scanning the crowd for her when Mrs. Lubin walked in. It seemed impossible to apply an adjective like pretty to someone like Mrs. Lubin, but she looked like a glittering and ferocious statue in her sequined blue gown. It was strange to see her in anything so fancy, and it wasn’t clear why she’d worn a gown—all the rest of the teachers wore simple khaki and sport jackets, casual skirts and sweaters. Still, I was honored that she’d dressed up for the occasion. I stood as tall as I could, hoping she saw me noticing her. Hoping she noticed me back.

I stood by the side of the stage, waiting for my big entrance. I watched as Becky Ruber sweetened the stage with her pious, raccoon-eared Esther, and as a feather-robed Mordechai shuffled alongside her.

As Ahasuerus took the stage, I started to get nervous. “Where is Vashti?” he barked. “The party has begun, and it’s time for her to dance for us.” To his fake party guests, he said, “She’s a wild one. She’s going to dance like a stampede. You’ll see! Tables will shake, and chandeliers will swing.”

But as I walked out onto that stage, made my first entrance, I instantly filled with the pure and pointed heat of being seen. I strode, swished slowly, moved like a majestic beast born into its grace. My long black mane swung over my bare shoulders as my hooves found their rhythm, the heft of my long tail sweeping back and forth against the backs of my legs. I stopped walking and blinked into my moment, my long, false eyelashes tapping me lightly on the cheeks. I felt as powerful as I ever had.

I looked out and immediately saw my parents in the second row from the front. They looked anticipatory, like they were waiting for something. For me to make them proud? To disappoint them? Bathed in spotlight, I realized I didn’t care. I felt eight feet tall on my hooves. I knew only a fraction of what I was capable of, I thought. I saw Mrs. Lubin in her shimmery blue, a whole head above the rest of the adults in the audience. I stood tall, towering over Ahasuerus, over my audience, like if I stuck out my tongue, I could taste God. Maybe this was what Mrs. Lubin meant by taking the opportunity. To strike awe. By the time I opened my mouth to speak, I was outside of myself. I was high, frightening, untouchable.

After the show, everyone poured out into the brightly lit lobby, and quickly, it got very crowded—parents, yes, but also a whole bunch of teenagers from other Jewish schools, most of whom I didn’t recognize. I looked around the room, caught Benjamin’s eye. He gave me a dorky thumbs-up. I was so high on my Vashti performance that I gave him one back.

I kept looking, moving through the crowd, as teachers brought out huge, heaping trays of hamantaschen and everyone began to gather around the tables. I saw my parents. There was Yaron, surrounded by a bunch of kids I’d never seen before. I saw our chemistry teacher, our Hebrew teacher, our gym teacher. But I didn’t see Mrs. Lubin. I couldn’t explain it, even to myself, but I started to feel frantic about finding her.

I walked up to Rochel, who had half a raspberry hamantaschen sticking out of her mouth. “Have you seen her?”

“Who?” Rochel chewed.

“Mrs. Lubin,” I said. I tried to make my voice sound casual.

“No,” said Rochel, just as Adira and Hillel gravitated toward us.

“Hey, what’s up with you guys?” Hillel had taken off his crummy demon costume and looked just like regular black-clad Hillel again.

“Just, have you seen Mrs. Lubin?” I could feel myself getting less casual every time I asked. It was so odd that after making such an entrance, she’d just vanished.

Adira shook her head. “Nope,” she said. Hillel shook his head, too.

I cleared my throat, trying to clear out the unreasonable panic rising to my mouth. “I’m going to check the parking lot,” I announced.

As soon as I stepped outside, the world out there felt jarring, like waking up too quickly from a thick dream. It was raining, and the ground was slick and black, the only light coming from the lobby behind me, bright with festivity and chattering attendees.

I realized right then that I was angry at Mrs. Lubin. I’d begun to understand that, in this life, other people so often had what I needed, and I’d begun to learn how to take it. But even though Mrs. Lubin seemed to have something I dearly needed, I had no power to take it from her. And I was angry because she refused to give it to me, or even to tell me exactly what it was. She was the first person I’d ever met who seemed like she might be able to explain me to myself. I was convinced now, after standing on that stage, that she alone could help me understand exactly what kind of monster I was, and what kind of monster I would grow up to be. Would I walk halls dotted with whispered speculations about my body? If I had something like a zipper, would I hide it and try to blend in with everyone else, or would I wear it proudly, like a crown, or a tail?

I walked through the rain in my fur dress, my tail wagging as I walked, my left set of eyelashes coming loose. I knew what I must look like, but I didn’t care—it felt so good to be a monster out in the open, under cover of the rain, away from all the other kids at Friedman. I’d been trying so hard to stay unobtrusively middle, but tonight, despite my best efforts, I’d ascended somewhere entirely else. It felt all the way on top. The things I’d been ashamed or afraid of? They made me better. Mrs. Lubin could tell me.

The parking lot was blurry wet and full of cars. No Mrs. Lubin. I walked around the side of the building, past the alley that was a favorite spot for making out between classes. I knew this because Lizzie and Noah frequented it. I walked around the bend, to where the carpool benches were, and where, once in a rare while, I’d caught a teacher smoking a clandestine cigarette. And there, sitting hunched over on one of those benches, was a commanding figure in glittery blue.

“Mrs. Lubin.” I said it almost inaudibly. I kept walking toward her. I heard my hooves beat against the concrete. As I got closer, Mrs. Lubin didn’t move much, and I was nervous, but strangely unafraid. The color of her gown shifted in and out of focus in the hazy dark and the rain. She’s beautiful, I thought, even though beautiful was not what I meant. Beautiful wasn’t important anymore. “Mrs. Lubin?” I repeated, and made it into a question. Saying her name out loud felt too intimate, like a thing I hadn’t earned. Why wouldn’t she answer?

I got close enough to see her clearly—the lumpy contours of her short, curly hair; the angles of her exposed shoulders; the width of her arms as they leaned heavy on her knees. I don’t know what possessed me then, but I touched her. I pressed my palm to Mrs. Lubin’s back.

“Mrs. Lubin,” I said. Her skin was damp and warm, and the sequins on her dress were scratchy. I made myself move my hand only a little bit, right to the center of Mrs. Lubin’s back, where her dress dropped down. And right there, at the center of her back, that’s when I felt it. The zipper.

Panicking, I drew back my hand. She seemed, from what I had momentarily touched along the zipper tracks through her dress, partially unzipped. My skin was racing. Now I brimmed with real actual fear, dearly wishing I hadn’t come outside alone.

I cleared my voice to test it and tried one last time. “Mrs. Lubin, are you okay?”

Slowly, very slowly, Mrs. Lubin turned around to face me. She looked down at me, her small eyes finding their way to mine.

“Daniela,” she said. For some reason, I expected warmth—another shared moment of some kind, congratulations on a show well done, some kind of acknowledgment that I’d been the only one special enough to be able to get this close, to learn Mrs. Lubin’s secret. But there was no warmth. Mrs. Lubin’s face was distorted with some combination of anger and fear. “You can’t know about this,” she said, her voice breaking into desperation for a moment. Then, collecting herself, she looked at me as coolly as she could and said: “You have to remember, Daniela. I know everything you did.”

For a minute, everything went blank. Was my teacher threatening me? Blackmailing me? I blinked, the wet eyelashes batting against my face, a reminder. I wanted to run back inside, clink a spoon against a glass, and announce to that whole lobby that I had proof, that there was a zipper. But I also wanted, with everything I had, to stay right there, right by Mrs. Lubin, and to follow her wherever she went when that zipper came all the way down.

“What?” My voice came out soft. I didn’t know how else to respond. I couldn’t stay there in that alley for another second, but I also knew I couldn’t leave. My feet wouldn’t take me anywhere.

“But as long as you remember that…” She shocked me then by putting her hand on mine. “Do you want to do it?”

“Do it?” I might have been crying, but it was raining so hard by then it was difficult to tell. “Wait,” I said. My chest leapt to my throat. “Do you mean?”

Mrs. Lubin guided my hand around to her back. She bent over a little bit, and I could see little droplets gleaming all over her thick and freckled skin. “Here,” she said, her gravel a low whisper now. “Quick,” she said. “Right now.”

Unbreathing, I grabbed the tab of the zipper, and, just for a moment, watched the way it tented her skin. Then, I pulled downward. I felt the tension of the zipper in the tracks, and then the give. I could barely look—there was just the ascending tune of the zipper as it sped open, the vibration in my fingers, Mrs. Lubin’s skin gone slack, Mrs. Lubin’s gown to the wet ground. Mrs. Lubin gone.

Just like that, the wet road that led to Friedman was dark and empty again.

I was dizzy. So dizzy. I thought, Unusually large. I thought, A threatening force. I thought, Highly successful.

I looked down. I knew to look down.

There, on the ground, only the pile of blue sequined gown. And next to it, just that zipper. Wherever she was, she was somewhere I couldn’t follow. And I wasn’t sure if she’d given me what I wanted, or if I’d taken it; perhaps both, or perhaps neither. Behind me, the world was unbearably normal. The lobby still buzzed with post-show conversation, and a few people had started to spill out the doors, back into the parking lot.

I stood on my hooves, brushed some of the water off my furry dress, trying to figure out how I could make myself walk back into that school with its silly rituals and its timid rumors and its middle kids, of whom I no longer felt any part. I closed my eyes, tried to make myself feel large. I looked down again. Still the rumpled dress on the wet ground, but next to it, a small evening purse I hadn’t noticed before. It was a matching royal blue, with a small clasp and a gold chain. And there, at the lip of the purse, a fat wad of crisp hundred-dollar bills, sticking out like an invitation.