Fiction

Gloria

by Reena Shah

Tall grass grows wild around the used cars and engine pieces sprawled across the Rolands’ yard. There are photos of Buddy and me, age four, sitting naked on the hood of a Porsche with no tires, both of us holding our balls. A kiddie pool with cloudy water. The sun overhead and our faces shadows and teeth. Our mothers are nowhere. We used to be friends.

“They do nothing to deserve such a lawn,” Dad says. It’s true, and still, witchy shoots race to the sky every spring. He walks around the patches in our yard, green zits in the dirt. Dad sweeps his palms over the stalks—thin, wispy, see-through. He seeds twice a year and chases the neighborhood dogs with a shoe. Complains we have too many trees, too much shade, that Ma won’t let him chop them down.

“It’ll all be washed out by the storm anyway,” I say. It’s September and just days before Gloria.

“We’ll cover them.” He makes me cut netting meant to keep raccoons out of gardens, but he can’t get the nails to hold in the dirt. After he gives up and goes inside, I pull out clumps of grass and hide them in the woods under beds of dry leaves.

That night, he goes on about the emergency broadcast system, the weather reports, the stocked grocery stores. “In India no one thinks ahead,” he says. But I crave disaster. Roofs collapsed into houses. Water lapping at front doors. Maybe somebody dies. I’m ready to steal provisions from our basement, float supplies out on toddler swimmies. People looking at me like I’m a king, like I’m their guy. I’d be okay with them feeling bad about how they’ve stared or about how they’ve avoided looking at me entirely. I’d be okay with their shame.

All week Ma and I watch the six o’clock news like we’re eating candy. Gayle King talks about securing trash bins and buying storm shirts for dogs. Ma likes that she’s Oprah’s best friend. The storm hurtles toward the Carolinas on Tuesday, then swerves to the right, heading straight for Long Island and western Connecticut. The 145-mile-an-hour winds slow to below 100, which sucks.

School is canceled for Friday at the beginning of the week. We stuff our textbooks into our lockers and push our desks into the middle of the room, away from the windows. Eventually they’re taped, just like the windows at home that Ma and I x out with black duct tape. I’m twelve and finally tall enough to reach midway up the pane, though I’m still the shortest in my class.

In homeroom, Ms. Harrington tries to teach us meteorology but gets the terms wrong and is confused between high and low pressures, the center and the eye. She’s an award-winning teacher according to the pale, yellowed certificate behind her desk. She still pronounces “Moksh” like it rhymes with socks, and each time I tell her “Mo” like “hoe.”

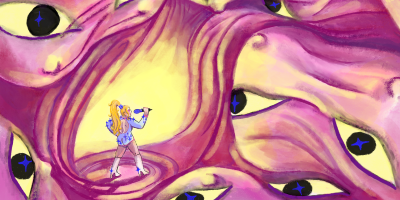

“Your name rhymes with douche,” Nicole Jones says. Her voice is soft and shimmery, and her square jaw juts out like it’s been cut with scissors. She’s got a girl on either side, their arms twined through hers.

“It actually doesn’t. It actually doesn’t rhyme at all.” I say it like an education. A crowd forms, and I see Buddy skirting the circle. He looks like his dad. Squat nose and large forehead and dimpled chin, but with his mother’s doughiness, like you can sink into him. We used to crush caterpillars and smear their green innards over our hands.

“Do you know what ‘douche’ even is, douche?” she says.

“You spray it up your dirty vagina.”

She doesn’t like this. Her freak eyes flash—green and blue and brown. She tucks her perfectly freckled chin into her chest and sticks out her tongue and bangs her wrists together. It’s a lame, unsophisticated move. Like my tongue does anything besides sit in its mouth. Everyone laughs, Buddy the loudest, because Nicole is what they call hot.

When we were little, Buddy liked to trace our faces with black marker. He’d press the felt tip down on the smooth slant of my corrected cleft lip. “Does it hurt?” he’d ask, and I’d shake my head and say it tickled. “Like a bad tickle?” I’d shake my head again. We got in trouble because the black was hard to wash out, but I liked it. I could pretend my face was a costume. The way my chin dipped, the way my forehead pushed forward, lips that didn’t fit over teeth, sideburns I shouldn’t have already had, my nose and its monster breath.

The day before the hurricane the air is calm, but the reports promise heavy wind and rain by morning. Ma takes a long shower that night, a last one before we fill the tub. When she gets out, she smells like hot pavement. Her housecoat stops just below her knees. After bath is the only time I see her legs, which are toast-colored and too thin. Dad sits at the dining table opening envelopes and laying bills in neat piles. “You should not take long showers,” he says. “And so hot.”

“I am not taking lukewarm shower and feeling cold,” Ma says.

“I am not saying for you to feel cold. I am saying for you to take shorter showers.”

“When I catch pneumonia, then you tell me.” Ma stares, but he won’t look at her. I want to say that pneumonia doesn’t happen that way. I want to say showers are just showers.

That night I hear water filling the tub. I hear muffled, lonely talk about money. We’re coupon clippers who never order second sodas at restaurants, until Dad goes on a spree. Lawn equipment, kitchen tools, ugly bedding that’s half-price. Every year they talk about Ma learning how to drive and getting a second car, and every year it doesn’t happen. We’re fine until we’re not. It’s like they’re children acting as adults.

Ma comes in to shut off my lights and then sits at the edge of the bed. She places a hand on my arm, and I think she might lie down and tell stories the way she used to. I can feel her breath pushing her belly in and out. I think about death, about the firefly I cupped in my hand until its electricity faded out. Ma used to say that our thoughts don’t die. That they travel to other heads so bits of you stare out another body that doesn’t know what’s happened. She stopped telling the story when I told her I never believed her, that there couldn’t be dead people inside our heads too. I knew that what I said was mean by the way the corners of her mouth twitched and then froze, but I didn’t take it back. Now I keep very still, hoping, until she leaves.

In the morning the sky is finally overcast, and Dad is dressed for work, like it’s any normal day. In India he trained to be a structural engineer, the only engineer in his family, but here he’s an assistant.

“Where are you going?” Ma asks.

“I’ll come home when it starts raining.”

“It could be suddenly.” Her eyes are wide, and Dad laughs.

“Do you see anything happening suddenly? Nothing here is like that.”

In Bombay they had monsoon seasons. Once I saw it on the news, people wading through water up to their hips with no expressions on their faces. Children swept out. Shit floating freely in the streets.

After he leaves, Ma tells me everything will be fine as if I’m afraid. She keeps the TV on, though there’s no special newscast, just the usual talk shows. She checks the bathtub again to make sure the drain’s plugged. She takes down her framed Vishnu, a gift from a cousin before she left. It’s a black canvas studded with beads and covered in glass. She puts her temple in her closet and lays all the gods on their sides.

“It’s not an earthquake,” I say.

“There will be high winds.”

I check the clock on the stove when I hear the first drops: 11:30. When Ma calls the office there’s no answer.

But it’s like any other rain. We could have gone to school and nothing would have happened. Ma’s nervousness is the only thing that makes it feel different.

We eat lunch. Crackers and sour tomato soup. The air in the kitchen is musty and green, like a forest and a bathroom combined.

“We’ll have to go downstairs soon,” Ma says.

“Why don’t we go down now and take our food with us?” I ask.

“Roaches.”

“But what if we have to stay overnight? For days?”

“It won’t be like that,” she says with an impatience I don’t deserve.

“It might.”

“We have candles and flashlights.”

“We’ll have to eat out of cans.” I want to bicker for fun, but she stands up and walks to the taped-up window. “Maybe the wind’ll knock down trees,” I say, but she isn’t really listening to me anymore.

The basement smells like detergent and cobwebs. We sit on the old couch staring at rectangular windows a few inches from the ceiling. All you can see is white sky. Once in a while a tree branch tosses back and forth like a maniac. The radio says nothing, just plays Laura Branigan over and over. “Gloria, I think they got your number. Gloria, I think they got the alias that you’ve been living under.” What does it mean? She’s Gloria, or she isn’t? But Ma won’t turn it off.

I have this feeling that if I leave the room, she won’t notice, because she’s only thinking about Dad’s drive home from work. I could go upstairs and stand by a window until the glass shatters and bits get lodged in my arms, neck, face. She’d scream when she found me sitting on the floor, calmly, expertly picking out the bloodied pieces. She’d regret not paying attention, and I’d forgive so easily she’d be stunned. But when we hear the garage door open, when Dad calls out her name, when he shows up at the foot of the stairs, she doesn’t react, doesn’t even see he’s there until he shuts off the radio. “How many times the same song?” he asks.

“Go have some soup. It’s cold,” she says and switches the radio back on. Sometimes they hold hands at the mall but it’s like they’re trying not to lose the other person, not like actual touching. Two people holding onto two ends of a rope.

The storm itself is lame, despite being the biggest storm to hit Connecticut since 1960, when Donna recorded 140-mile-an-hour winds. Gutters don’t overflow, and a day later the streets are barely wet. Not a single tree in the neighborhood comes down.

But the electricity goes out. We have to light the gas stove with matches and walk around with flashlights. Dad doesn’t trust that the water won’t run out, so we take bucket baths with the water in the bathtub, lint and stray hairs floating on the surface. I fill my bucket halfway and drag it to the stand-up shower in my parents’ bedroom. Ma supervises to make sure no one fills a bucket to the top. She doesn’t know that I don’t soap up, just squat there between bucket and drain, the cold tile skimming my ass, wetting my limbs and splashing the walls to make bath-like sounds.

There’s not much to clean up, except that our yard is covered with claw-like branches. The mud’s thick, and Dad loses his flimsy sandal with its frayed toe strap every few steps. “Look at this,” he says, pointing to more mud and drowned wisps of grass tangled in netting. I’m kicking through puddles in the drive, not wanting to help. Across the street Ran Roland watches. Dad nods at him, and Ran raises a hand.

“Mornin’.”

Ran’s cars are all colors and sizes. He and Buddy are often bent over hoods, hips touching, Ran’s beers sweating on the driveway. I don’t know anything about cars, but I like to watch the two of them unload whatever they’ve found from whatever dump they’ve been to, like dragging a sea mammal to shore. The cars sit heavy in the lawn, broken and useless but spoiled.

Ran stands in his yard, hands on his hips, looking up and down the street, the way people do when they’re getting ready to cross. But he stays where he is.

“You got your hands full over there,” he calls out.

“Hands full, yes,” Dad says.

“Had to bucket out half these cars. Could’ve left them, but the smell, that’s another thing.”

Ran is on disability from an accident at the Pratt & Whitney plant, and Dad says the accident doesn’t stop him from his car work.

“I’ll bring over seed for when things dry out,” Ran says. “Drop it off during the day.”

“Oh, no need.” Dad rocks back on his heels and gives the smile he keeps for people he doesn’t like.

“It’s nothing. They’ve declared a state of emergency. A ploy to get dollars from Reagan for a couple fallen branches.” Ran shakes his head.

“And what about the power?”

“The power?”

Dad points to the electricity lines.

“Well, that’s hardly Reagan’s fault,” Ran says with a shrug. Dad chuckles, though Ran doesn’t mean it as a joke.

The power is still out on Monday when school reopens and Dad goes back to office. He calls it “office” instead of “the office.” As I walk up the hill to the bus stop, the dog I hate bounds across the Stuarts’ yard. Red eyes and black-and-white fur forever matted to its stomach. It smells like fish and licks my face. Sometimes I yell at it and once I kicked its belly. But it keeps coming. I never call it by name.

At school, Ms. Harrington has us write headlines for the storm. I write “STORM SUCKS” and Ms. Harrington encourages me to use more powerful language. Everyone tells stories about trees almost falling on their houses and the flooding in their basements and making s’mores over candles. I’ve never had s’mores and think everyone’s a liar. I could lie too, but nothing’s good enough. It’s become a thing to walk by me and make the same face Nicole made—tongue out, eyes bugging. I pick my nose to gross them out. At lunch Buddy sits at the end of a table full of kids and nods when people talk. Someone calls him a fat fuck for eating all his lunch and he laughs like it’s funny. I poke at my peach cup and pretend I don’t notice.

“You fucking smell,” Buddy says when we get off the bus.

“Like your mama.”

I expect him to insult my own mother but his eyes harden. “You can’t fucking talk about my mother.”

“It was just—”

“I’ll punch your shitty face if you do it again.”

“You could.”

“Shut up.”

“No, I mean it.”

“You’re an idiot.”

I want to tell him that I don’t want him to punch hard. Just enough to make me bloody and injured instead of disfigured. It wouldn’t last, but maybe the bruises would get darker before they got lighter.

“If you punch my face, I’ll fix your homework,” I say. He can barely multiply and spells like a kindergartener. I help kids cheat. It doesn’t make them like me, but it makes them need me.

“I’m not fucking touching you,” Buddy says before he disappears down the road.

I pick up the mail—more bills and circulars. An ad for security systems. Once in a while there’s an airmail letter that Dad reads aloud in front of the TV. The other houses have mailboxes that look like birdhouses, but ours is metal and rusted in places.

The front door is open, which is odd. The screen is closed, but the door behind it, which is usually locked so I have to knock to get in, is wide open. I notice the smell—minty and sharp—before I see Ran sitting at our kitchen table, his face red and veined like the underside of eyelids. “Hi there.” He sits with his legs crossed, his arm thrown over the back of the chair. I feel like I shouldn’t look at him, like I’m seeing a private part.

“Hello,” I say.

A pot of chai is about to boil over. Ma is wearing the blue salwar kameez with paler blue flowers. Her hair’s braided with frizzy flyaways sprouting at the temples. The same gold studs in her ears. But she looks different, too. In the eyes. Brighter, maybe, or just focused.

The table is empty and small-looking with Ran there. I’m embarrassed of our shiny, mustard-colored wallpaper peeling at the top and dark brown cabinets with paint that scratches off easily and gets stuck in your nails. Ma doesn’t take my schoolbag like she always does. Instead she turns away and filters chai into two mugs.

“Ran brought lawn seed,” she says quietly. “And a flashlight because ours are without batteries.”

“We have so many flashlights.”

“All of them. The batteries have died.”

“We can get more batteries.”

Ran holds out a bright red flashlight. “You can hang on to this one for as long as you need.” He talks to my shirt, just below the neckline, which would be a problem if I were a girl. I take the flashlight and place it on the floor between us, close enough to his shaking foot that he could kick it away. The sole of his shoe is like a slab of wood, thick and uncomfortable-looking. I feel naked with my bare feet.

“We don’t wear shoes in the house,” I say.

“Moksh,” Ma says. The mugs must have been hot in her hands, but I don’t move.

“Of course. It slipped my mind,” he says, and bends over slowly to untie the worn-out laces, which makes his face redder. His socks are thin and show his toe knuckles, skeleton feet covered in skin. It makes me think he’ll die soon, and I don’t feel bad for him.

He doesn’t draw his shoes together or push them under the table and out of sight. I look at Ma who is still holding the cups, like she can’t put them down until I leave.

“Mokshu,” she says. “You should do your homework before dark.”

“I don’t have any homework. We’re in a natural disaster,” I say.

There’s something about Ran that feels loose and stretched out. He looks at Ma straight in the eyes, with his head slightly bowed, a smile on his lips. “Your mother was telling me about what a good student you are.”

“Sometimes Buddy needs help with his maths, Mokshu, and I said you could tutor him.” In the dirty kitchen light, she’s glowing, her face lit from inside, a light I never see directed at me or Dad. With us it’s either tension or worry. Sometimes I want to shake Dad until the hard parts of him fall out. I think of the grass I hid in the woods, whether it’s still there, whether I can sew the clumps back to the earth and throw Ran’s seeds in the trash.

“Fine,” I say, and leave them alone. She thinks she’s helping, and I almost feel bad about what she doesn’t know. It’s hours before Dad’ll be home, that nothing time of day when the afternoon sun floats behind black branches. Sometimes, Ma plays scratchy film songs or Donna Summers, and glides around the furniture shaking her head and hips, a little on her toes, and I watch from the hallway, and she pretends she doesn’t see me. I worry it might never happen again, that the world has shifted, but not in a way I want.

When he’s ready to leave, Ran uses Dad’s shoehorn, standing awkwardly in the foyer. He’s tall enough that if he starfished his arms he could touch the ceiling.

“That was quite a cup of tea,” he says. He wipes his brow with the back of his hand and winks. Ma laughs and plays with the cuff of her sleeve, trying to twirl it around her finger. I’m standing right there if they want to see me.

The red flashlight hangs over the table for dinner that night. Ma heats half-frozen daal that we eat with Wonder bread. She arranges the cucumbers and carrots in a careful circle around cherry tomatoes on the verge of going bad. But Dad doesn’t notice the effort.

“I’m sure the power is back in the new developments,” he says.

“Maybe. But it’s just a few days. We’re lucky to have a gas stove,” Ma says.

“What lucky?” His eyes fall on the bag of seeds on the counter.

“They’re for you.”

“What for me? He is just giving because his soil is so good.” He slaps the table. “If we cut the trees.”

Ma drags bread through daal around her plate, muddies the blue trim. They’re supposed to be flowers but look like beetles. “We will not.”

“And why not?”

“It will do no good.”

We all know this is true.

Ma watches me eat. Daal drips down my chin and crusts my fingers. I only eat half of everything, and I can tell she wants to comment, to reach over and wipe my face. Nothing we do is going to make us like other people. Not grass, not a normal face. I shout these things in my head and squint at the flashlight until black spots swim in my eyes.

After dinner I slip out and no one notices. Our house is the only one still with tape on the windows, and from outside it looks stunned.

The street is empty. The dog that I hate is barking, but that’s it. I could have been alone in the world, the last person left.

There is one car that’s just body. No engine, no tires, no steering wheel or seats inside. The body is blue and sleek, the front lower than the back, like it’s narrowing its eyes. I’m expecting a fake door that doesn’t open or one that takes many tries, but it opens easily and throws me off balance.

The inside is damp. I have never been in a car with no seats, and I’m surprised that I can stand up and walk around in it. My head skims the ceiling in places, and I feel gigantic. I feel good.

The dashboard is stripped except for the odometer and other gauges and dials I’m not familiar with. The floor is sticky but pleasantly cool. I lie down and wait for night to fall. The car is by the woods that separate the Rolands’ house from their neighbor’s and not the first place anyone will look. I stare at the ceiling and watch it turn darker as the last light fades.

Time moves irregularly after that. I feel like I’m lying there for a long time and then I hear Ma’s voice and my heart races. She’s calling my name. I hear Dad tell Ma not to worry. That she’s being overprotective. That I can’t be far. If he calls the police they’ll tell him that it’s too soon for them to do anything besides what he and Ma are already doing. We all know that from shows.

By the time I hear Ran and Buddy, it’s so dark I can only see the outline of my hand in front of me, one dark thing against another dark thing.

“When was the last time you saw him?” Ran asks.

“He went outside after dinner,” Dad says. “But he should have returned by now.”

“It’s past eight.” Ran’s voice is thick and marbled. “Buddy can ride up and down on his bike, right, Bud?”

Buddy doesn’t say anything, so he must have shrugged or nodded. “Mom!” he calls.

Maybe Eileen has been there the whole time, in the door, on the threshold. “It’s dark as hell out here. You’re not going anywhere.”

“But Dad said.”

“Your father doesn’t get to say,” she says. “You stay in the yard.”

I hear a car and then silence, like the night has swallowed every sound. If I stay, I’ll have to think about supplies. Eventually, everyone will fall asleep and I’ll take sips from the hose outside. I’ll watch the dawn break through the windows and push past my hunger.

I see Buddy before he sees me. He has his face against the glass, cupped by both hands. From below, it looks like his head has no body.

When he does see me, I put my fingers to my lips to stop him from calling out. He looks around before opening the door.

“What the fuck?” he asks. “Did you fall asleep in here? You know people are looking for you.”

“Don’t tell,” I say. “Please.”

Buddy considers and then steps inside. The whole car shifts. I nudge over to what would have been the passenger side and prop myself up against the door.

“You want to tell me what the fuck?” he asks again, but quietly.

“I’ll come out eventually.”

“My dad’s drunk.”

“Oh.”

“He’s driving around with your parents.”

“Okay.”

“What? Do you hate them or something?”

“Do you?”

He makes a rough sound in his throat. “My mom’s pissed.”

“Are you going to punch me now?”

“Will you fucking stop. You’re a fucking freak.”

A freak. It’s fine, I want to say. It’s fine that I’m a freak, at least it’s something. I wait for him to leave, but he stays. The air is close and thick but I’ve gotten used to the smell, like the smell is inside me now.

“During the hurricane you could swim in here. Water up to the windows,” he says.

“It smells.”

“You smell.” But there’s no bite in it. “You can’t stay in here forever.”

“I told you I wouldn’t.”

“It’s not your property.”

“Why do you care what I do?”

He taps his head against the door. “I don’t care. But I bet your parents could die because of my dad.”

I imagine Ran slamming the car into a post or driving it into Crandall Pond. I’d maybe live with Buddy and Eileen until the state decided what to do with me. Eventually, they’d figure out it was my fault and maybe I’d go to juvenile detention or a halfway house. Maybe my parents would float around inside me, and I wouldn’t even know it.

Buddy used to like tigers—tiger sheets and bedspread and stuffed tigers lined up on a shelf in his room. Tiger T-shirts every day until the kids said it made him look like a fat turd. I could’ve laughed but never did, though I’m not sure if that makes me kinder.

“Your dad was at my house today,” I say. I feel Buddy go stony. I feel him suck in air but not release. My eyes have gotten used to the dark, and I can kind of see him glowing there, his wide forehead, lips outlined in pink chap. “He dropped off seeds. Flashlights. Talked to my mom.”

I want to say that I told him to leave. That I dragged him out with superhuman strength, not caring that his head banged against the porch steps, leaving a bloody trail. “He said you can barely do math.”

“Fuck you.”

“He said you can’t spell.”

“Fuck off.” Spit flies from his mouth.

“He likes my mom’s tea. He kept making excuses to stay longer.”

“Fucking freak show. You’re a fucking freak show.” He’s growing now, swelling with the damp air. A car approaches. Ma crying still, breathless moans that rise to the surface. Something in me rises, too, but I can’t leave, not yet. Let them find us. Let them tear the door open, let the damp stink slap their skin. I lean forward, offer my face. Wait.