Fiction

The New Middle Class

by Dolan Morgan

“Take your time, Amy,” Dr. Kenston says, as if time were a thing to be taken. As if a doctor could forget that it’s time that does the taking.

“Breathe,” he says, and I do. We all do. Michael, me, everyone in the world. We all follow this doctor’s advice for a while. Of course. But then.

Christ, Michael.

Michael is calm, somehow. I can’t understand it. He sits in his wooden armchair, here at the large desk, in this awful hospital, and smiles. Like he is faced not with mortality but merely a pointless decision between shades of paint. Pleasant tones, clever names. Muted greens. Shallow blues and slate. How does he still have access to such ease and serenity, I wonder. Is there a secret pool of knowledge that can only be accessed through illness? Must we trade good health for a single, pure fact about the world? Something otherwise hidden that might, in its revelation, bestow upon Michael great calm. Maybe he has this knowledge but cannot share it with anyone, not even me. How painful that would be for him, I think, to keep that secret. “Just take your time, Amy,” Dr. Kenston says again. Why is it so much easier for me to indulge in imaginary burdens than to actually face the ones right here in front of me. Muted greens. Shallow blues and slate. Michael is utter calm, just air, just nothing, and I’m jittering, anxious, unfolding like some failed paper plane, even though it’s Michael who’s dying, even though it’s Michael that time is taking.

“Amy,” he says, “I’m ready whenever you are. We can do this.” I am thirty years old. He puts his hand on mine in the office in the hospital in the city where we live. He is almost thirty-two. I’m not ready. I’ll never be ready.

“I’m ready,” I say.

Dr. Kenston nods, rotates his chair closer to Michael’s, plants his feet on the pink tile and adjusts a white coat. “This will only take a moment, it’s very brief,” he says, all empathy and comfort. He rolls up Michael’s sleeve, administers a small injection, then asks Michael to recline his chair and unbutton his shirt. Dr. Kenston rubs an acrid solution over Michael’s bare belly. “You’ll feel a bit of pressure,” he says, revealing a knife.

Dr. Kenston makes an incision in Michael’s abdomen, maybe four inches long on the right-hand side, and then swabs away the blood. There is a lot. He massages the flesh around the opening with his large hands, first in broad waves and then in tight circles. Michael smiles at me, nods, always an anchor. The doctor leans in close to the wound, as if to smell or taste it, and begins to whisper. I cannot hear what he says.

“Take your time,” I imagine, or, “Breathe.”

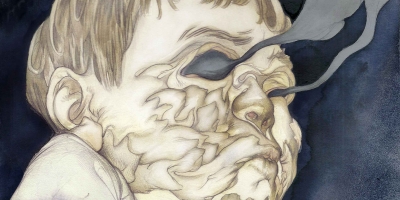

Then the skin spreads apart, as if on its own, and the Replacement flowers out. Its brown, rippling head slips from the wound, then more of it. White layers of fat gleam where the cut has stretched tight.

I see the serenity fade from Michael’s face. Whatever pure truth had been granted him by illness, it is gone now.

The Replacement is at once like a large tongue and a hard, knotted root. I know it’s a natural part of Michael’s body, inasmuch as death is a part of any body, but I can’t conceive its humanity. A wet winter branch teasing through a hole in the fence. It projects from Michael’s side, half in half out, and turns toward the light.

The Replacement stretches as if yawning, then gurgles out a mix of mucus, bile, and blood from what must be a kind of nascent mouth.

“Hello,” the doctor says to the Replacement. “I’d like to introduce you to someone. Her name is Amy.”

“Hello, Amy,” the Replacement coughs.

Over the next few months, I accompany Michael three times a week to sessions intended to better acquaint me with his Replacement.

At first, Dr. Kenston needs to remake the incision at the start of every meeting so that we can commence our small talk, icebreakers, and goal setting. This is how we begin to know each other. The doctor cuts Michael open, leads us through a series of interpersonal sharing games (quizzes, confessions, trust falls), and then packs the Replacement back into its hole. It’s clean and easy. I talk about my childhood. The Replacement asks questions about what it means to be alive. Michael tries to transfer his anxiety about death into joy for the Replacement’s burgeoning new life. “It’s really exciting,” Michael says, clenching his fist. When we leave, I can almost pretend it isn’t real.

The doctor’s incisions quickly become unnecessary – because the Replacement stops retreating into Michael’s body at the close of sessions. Too big. It’s like a toddler now, or a sack of wheat, but pulsating and white. When I see a zit that needs popping, I can hardly help myself. This is no different. The two of them together, Michael and the Replacement, are near to bursting. Michael’s skin: fitted sheets on a hotel bed, begging to be ruffled, ripped and tossed aside.

The Replacement cannot possibly fit there, I think, every time I see it, but the thing simply remains dangling from Michael’s side at all times. On the car ride home. At work. In bed. The bathroom. Everywhere. There is no getting away from it.

Michael struggles with this sudden loss of privacy. It’s too much for him, and he wants to discuss it at the next meeting.

“I don’t have time to myself, either, you know,” the Replacement says bitterly.

Michael starts to interrupt, but Dr. Kenston reminds him that the Replacement has the talking stick right now. “You’ve lived a whole life on your own, Michael,” it says. “I’ve never had that. I’ve never been by myself. Never even existed completely outside of your abdomen.”

I consider the moments in my life that I’ve been truly alone, versus the times I’ve been irretrievably wrapped up in the body and life of another. I can’t remember when I stopped being shocked at their inevitable intersection.

With Dr. Kenston’s help, we reach a sort of compromise. When Michael needs time to himself, the Replacement will wear a small hoodie and submit to swaddling.

At home, we give it a try. “I’m glad we talked this out,” the Replacement says and wiggles into his little sock. It’s new and gleaming. Then Michael pulls him against his chest and stretches the swaddling scarf around them both.

It looks ridiculous but kind of works, so Michael and I kind of have sex. It’s sloppy, rehearsed, and almost depressing, and in some ways doesn’t so much happen as pretend to happen, but it’s better than nothing, I think.

In this way, life is somewhat normal for a time.

But the Replacement is not satisfied. He also wants to be by himself. Dr. Kenston says that’s his right, of course. Apparently, there’s a hood for that too.

At home, we give it a try.

I drag the large cloth bag over Michael’s head, then pull it down to his feet and help the Replacement poke through the pre-made hole. I guide Michael to the floor, where he stretches out by the coffee table, and I cover him with the additional solitude blankets. He shuffles a bit, then goes still.

The Replacement looks like a potted plant left atop unwashed clothes. Michael doesn’t look like anything at all. Like nothing.

“Why are you crying?” the Replacement asks.

I lie down next to the pile of blankets and rub my hand along its soft fabric.

“This is my time to be alone,” the Replacement says. “Aren’t you going to leave?”

I can hear Michael breathing, can feel the warmth of his body, but I can’t see him. I can only imagine him. When I was a child, I would crawl out of bed and press my face to the floor like this. I would rub the carpet on my cheeks and try to picture the whole universe. The ocean, other planets. Michael shifts a bit. I close my eyes and pull tufts of blanket tight into my hands. I can’t squeeze hard enough.

“You know what’s funny?” the Replacement says. “Soon it will be Michael that dangles from my body.”

Muted greens. Shallow blues and slate.

When Michael becomes paralyzed and unable to speak later that summer, the Replacement has already completed his physical therapy sessions, through which he has grown in strength and size, learning to walk and wear Michael’s clothes.

When we go to the grocery store, the Replacement likes to use a shopping cart to help support Michael’s useless body. The Replacement grabs the spot where the two of them are still connected (around what you might call the hips—the Replacement sprouts now from where Michael’s pelvis used to be, pushing everything else aside), so that he can swing Michael’s torso up onto the cart, then wheel him along. It’s a relief for everyone. Otherwise, Michael tends to look as if he’ll rip right off and fall to the floor. Like deli meat. Pulled pork slipping from the roast. But always wheezing too. We walk like that, the three of us. I show the Replacement how to shop. What to buy and how much. The Replacement looks on in wonder. And Michael reaches out from his wire cage, trying to grab at all the foods I know he loves.

The Replacement begins attending professional-development workshops to smooth his transition into Michael’s old job at the university. As is customary, the Replacement adopts the name “Michael.”

Michael lives with me in our home. Michael needs to be fed and washed. Michael eats dinner with me and helps clean around the house. Michael sees and acknowledges my presence, I think, and he knows that I am here. Michael learns to ride a bike, order takeout. Michael dangles helplessly from Michael’s body, like toilet paper from the bottom of a shoe.

Dr. Kenston says it’s clichéd to compare our situation to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, but I don’t care what’s clichéd and what isn’t if it hurts this much.

He says my line of thinking is akin to a fear of vaccinations: ill conceived and misinformed, lacking all footholds in medical science. But even I know that grief exists beyond the reach of facts.

He says stop interrupting, that he has the talking stick, that I need to internalize the idea that cancer cannot be cured, that we can only manage and learn to live with it, that allowing our ailments to evolve into productive members of society is maybe even better than a cure. Symbiosis. I feel sick.

Finally, he says, there really is an afterlife, but we don’t have to wait for it. It is here with us now, and it’s willing to form a new, reliable labor force.

When I break the talking stick over the afterlife’s knotted, wormy face, the afterlife weeps a little and then cowers away from me, so Dr. Kenston refers our case to a specialist.

Which doesn’t matter, obviously, because Michael is going to die. We all know that now. And, no, I don’t mean Michael. I mean Michael. He has to go.

I stare into his drooping eyes, hoping he understands just how much I’ve accepted this, and with what certainty.

Autumn comes, and with it sweaters, scarves, and the distant smell of burning wood. Amy says that my affection for every saccharine trope of the season disgusts her. Oh, Amy. Still, I am happy to be wrapped up in all this warm cloth. It takes me back, back before the funeral, back when I lived inside a man. I felt so glorious during the “peeling” ceremony, when they pulled us apart (the relief! the release!), but autumn helps me remember my friend.

And the flavors! I can hardly contain myself with the flavors.

I am waiting in line at the cafe for a pumpkin spice latte, and probably I will die from too much joy. I am thinking about warm cinnamon and crunchy leaves and pie when I notice my server is a Replacement, too, fully grown. This discovery isn’t unusual by itself (Replacements work in every branch of industry), but by sheer coincidence, this one happens to be named Michael. That’s my name! I can hardly believe it. How many Michaels are there in this world? Nobody told me!

I admire him from my place in line. He’s awkward, stumbling through the motions, but he’s here and working, which is admirable. Good for him.

I think of the life out of which he must have grown. Somewhere, another Michael, one I’ve never met or known, withered in front of his family, which is hard, and out of that failing body emerged this earnest barista, which is hopeful.

Yes. He gives us all hope, I say to myself, as the barista fumbles with change and gets flustered at the register, saying, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” and crying into his twisted hands.

A wet winter branch teasing through a hole in the fence, Amy always says. About me. Which I’ve never really understood before now.

He so obviously does not belong here. I mean, nobody belongs here, really, and we’re all just lucky to have this rare opportunity despite the odds, I know I know, but I hope I’m luckier than this poor idiot.

At home, Amy is cutting vegetables. Well, not really. She’s standing over the sink with a large knife in her hand, a pepper on the counter. “Don’t fucking talk to me,” she says. “Don’t even look at me.” It’s a thing we do from time to time. You know. Or it’s a thing we do, minus the knife. The knife is new. Amy stares at it like it’s the first time she’s ever seen it.

Anyway, I know my cue. Gotta give Amy her space.

In the living room, I drag the large cloth bag over my head, then pull it down to my feet. I get on the ground. Through the little hole, I pull over the extra solitude blankets. I stay perfectly still and don’t make a sound. Just the way she likes it.

Then I hear a rustling along the carpet, feel something press along my back.

I can hear Amy breathing. I can feel the warmth of her body, but I can’t see her. I can only imagine her. I close my eyes. I feel my cheeks. The ocean, other planets. Muted greens. Shallow blues and slate.

I hear Amy say my name and feel an ache I don’t understand. There’s something I need to ask her soon. I really want to know. On certain days, how can you tell the difference between autumn and spring?