In Conversation with

Amelia Gray

by Amy Stephenson

I met Amelia Gray in 2012. She’d written a novel called Threats, and she was on book tour. I work at a bookstore, and had been tasked, at the time, with hosting her reading.

Don’t tell my boss, but I hadn’t read the book before her event. Instead, I began poking around on the internet to try to get a feel for her, and what I found was a video of a woman on a stage in Los Angeles (where Gray lives) screaming at her audience. She had written threats on slips of paper. She’d shout them at her fans, and then throw them into the crowd.

I was riveted, and smitten.

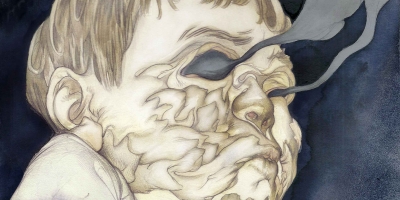

Gray now has a new collection of stories out (her third) called Gutshot. And it lives up to its name.

Each story in Gutshot is like a microclimate of the human experience. Mundane things—dates, families, a visit to the doctor—become grotesque or contorted in such a way that suddenly a truth about the way we interact with the world appears in sharp relief. Sometimes this is funny (see: “Curses,” “Fifty Ways to Eat Your Lover,” “Date Night”). Sometimes, this is tragically sad (see: “How He Felt,” “In the Moment”). But almost always, it is physically uncomfortable.

Flesh is literally sloughed off to reveal the bones and viscera (appropriately, a section of Gutshot was almost named “Viscera”). People crawl around in the walls of houses. Lovers physically devour each other. Hers is a strange world, but after spending an afternoon there, the anxiety I think we all feel about being alive starts to make a bit more sense.

I chatted with Amelia to learn more about how the “real world” becomes her fictional world.

Amy Stephenson: I read a lot of interviews you’d done while I was thinking about what to ask you, and the general consensus seems to be that your writing creeps people out. They all say it’s amazing, but that it’s upsetting as well. What does that feel like, as a writer? Is that your intent?

Amelia Gray: My intent, most broadly, is to tell a story well. Sometimes part of that means making myself uncomfortable. I spend so much time thinking about other people’s feelings in regular life, so much so that it wears me out. I think about other people’s thoughts and feelings when I write essays and when I’m at the grocery store. Everyone does, I think, which is part of why we end up so tired at the end of a day when we’ve interacted with a lot of people. I try not to think about readers when I’m writing fiction.

Stephenson: This is super interesting to me. I think you’re right: we all think about others’ feelings more or less constantly. Do you think writers, and maybe women, do it even more?

Gray: Well, writers benefit from empathy and women are encouraged culturally to obsessively care for others in ways involving wet wipes. Those are two different conditions, but they obviously inform one another. A little well-chosen selfishness can go a long way in the pursuit of beauty.

Stephenson: While we’re talking about being uncomfortable, you’ve talked in the past about how being uncomfortable allows for growth. Your characters, though, seem completely at ease with the things that make your readers cringe. Are your characters comfortable? Why the disconnect?

Gray: Sometimes they’re comfortable because it’s the life they’re used to, what they’ve built for themselves. For example, when the woman in “House Heart” is listening to someone crawl around her ductwork, she’s more or less at ease because she made herself feel comfortable with the idea of this element of her partner’s desire. Everyone develops an ease with their own lives. There are many elements of my normal life that would seem cringeworthy to another person’s normal life.

Stephenson: This is so real. Like, does the janitor go home and take a shit on his floor? Because it kind of makes sense that he would.

Gray: Oh, absolutely. My characters are much more motivated than I am to discover things about the world. They have less to lose because they don’t exist.

Stephenson: In Gutshot, your characters seem detached, either from themselves and what their bodies are doing (someone accidentally washes off part of his own face, or someone can’t figure out why they are always throwing up), or what other characters are doing (there is blood in her bra and suddenly he’s thinking of a dozen unrelated things), or just sort of detached from reality at large. The feeling I got was sort of like watching your stories from a high, remote place. Is this how you see the world? Do you think that’s a pattern in your work?

Gray: It’s a pattern in this collection, at least. A feeling of disconnection or remoteness usually indicates some kind of depression in me, but I wouldn’t say that’s why I’m doing it in these stories. The bloody bra one, “In The Moment,” requires that he think of other things, because the point at the end is that he’s achieved this ability to regard one element of life with precisely the same weight as anything else. That’s not a random choice; it’s kind of the thesis behind that story—asking if it’s good or bad to detach in that way.

Stephenson: I love that story. Like, it stopped me cold. Why did you choose to start the collection with “In the Moment”?

Gray: Thank you! That story really frames the book for me. I wanted to call the collection In the Moment for a long time because you see that happening over and over—characters either rejecting the present moment, or choosing to exist only within it, removing past and future. Or there’s an action or choice made in a moment which changes the world. In that way, any collection could be called In the Moment, though. Also, I didn’t want to mislead the kind of reader who would pick the book up for its gentle title and then have some traumatic response. I have enough to deal with.

Stephenson: I want to talk about “Date Night,” in which a restaurant scene devolves into disintegrating bodies and screaming diners. Was this inspired by a dating experience? Please say yes.

Gray: I wish! Best date ever. “Date Night” is more about being alive in general. I wrote it a couple years ago with the idea that I would read it out loud, because I wanted to yell about what it feels like to be alive. We don’t get to be alive for very long! I read it again last weekend, and it still feels good.

Stephenson: Oh man, I would love to hear that live. You like yelling at live shows. There are videos on the internet of you from your Threats tour screaming threats off of little slips of paper and then throwing them into the audience. I love the way you use the adrenaline during live readings, and how people respond to it. It’s incredibly refreshing. What’s that like for you?

Gray: It’s thrilling! I go into a place. I did a reading two nights ago where I figured I’d get up there and explain my rationale for writing “Fifty Ways to Eat Your Lover” right before I read it, because I’ve already seen reviews and interviews calling misandry on it. I wanted to say that I love men without shame or guilt, I’ve loved certain men to distraction, whole eras of my life have men’s names on them, and moreover that particular story is actually one of the most tender love stories I’ve ever written, the kind of love where both parties want to consume each other. It’s like from Punch-Drunk Love:

Barry: I’m lookin’ at your face and I just wanna smash it. I just wanna fuckin’ smash it with a sledgehammer and squeeze it. You’re so pretty.

Lena: I want to chew your face, and I want to scoop out your eyes and I want to eat them and chew them and suck on them.

Anyway, I had all that planned out, and then I got up and tried to make my little speech but totally failed and, at a loss, sang the first minute of Shania Twain’s “Still the One.” Why did that happen? I didn’t know I knew the lyrics to “Still the One.”

Stephenson: See, that’s so unexpected. I confess I am totally one of those people who thought MISANDRY when I read that story. I adore that story. But looking again, I can see what you’re saying. When you’re in love, even the annoying things aren’t annoying, which is terrible, but true. [For context, “Fifty Ways to Eat Your Lover” is a list of ways to respond to a man being in love with you, told in second person, that goes on for several pages. Here’s a sample: “When he asks you to marry him, panfry his foreskin.”]

As someone with body issues, I find it paradoxically refreshing the way you reduce bodies to parts and strings and viscera. I’m wondering how you think about bodies, and your own body, and if breaking bodies into parts helps you in some way.

Gray: I’m glad it’s refreshing. I look at my own body as a collection of parts that is either doing well or not so well, depending. I see one doctor for my spine and one for the dots on my skin and one for my eyeballs and one for my feelings. Even if you don’t consider how our little corner of the world encourages women to piece themselves up in order to pluck and improve slice by slice, it’s a vivisecting thing.

Stephenson: It’s hard for me to articulate body things, because I’m still unraveling it myself, but I really love this. The bodies in your stories aren’t indifferent. They respond and react to the atmosphere around them. Which, obviously, bodies do in real life, but I think it’s easy to forget that.

There’s a moment in “Curses” where the mother, who is writhing and losing fingernails, clearly states that she has a demon and the doctor is sort of like, “Well, let’s not jump to demon conclusions,” and I actually laughed out loud because that’s exactly my experience with doctors, and, often, with my own brain. I’ve been told I live from the neck up.

Do you think about how to knit together body and environment? Be my therapist, Amelia.

Gray: Oh honey, I’m doing the best I can. My body in the past five or six years has given me the strangest reactions to stress. When I was finishing Threats, I would wake up some nights scratching my legs—there would be blood on the sheets. Before that, I had night terrors pretty frequently and once broke a thin window and cut my leg. I was kicking it in my sleep. These days I’m not itchy, but I have terrible hives. I was remembering a difficult conversation I had with a friend and my skin started rumpling up in the memory of it. I get hives on my eyelids.

The brain is the most powerful machine on the planet. You don’t want it working against you.

Stephenson: You wrote two short story collections (Museum of the Weird and AM/PM), and then a novel (Threats), and now another story collection. Did writing a novel in between change your approach to short stories for the new collection?

Gray: I never stopped writing short stories. The oldest one in here was written right as I was editing Museum of the Weird, but it came in too late to be included in that collection. It’s particularly nice to write short stories while I’m writing a novel because it gives me a chance to stretch out my legs a little, take another set of characters for a spin.

Stephenson: Did you like writing a novel? Do you think you’ll write another?

Gray: I did! I am! Writing a novel seemed like such an impossibility to me when I had just begun writing and was feeling my own impatience with every story, the desire to close it and begin again. I still often feel that impatience, but every few years I find something which can sustain my curiosity for years. Which is lucky, because it takes me years to write a novel.

Stephenson: What are you up to next?

Gray: Scooping out eyes. Chewing on eyes.