Nonfiction

Your Dystopia Was Fab

by Jason Diamond

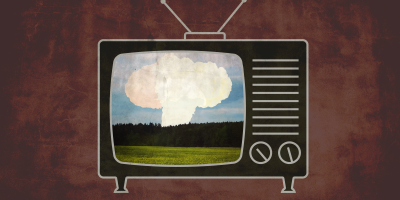

I first realized the world could end at any moment around the age of five while watching the video for the song “Land of Confusion” by Genesis. I’d heard one of my parents mention “The Button” at the dinner table, and held a vague idea of Good vs. Bad thanks to cartoons, but until I was in front of a television watching the terrifying puppet versions of Phil Collins and the rest of the band, as well as Ayatollah Khomeini, Mikhail Gorbachev, Muammar al-Gaddafi, and our own President Reagan in some nightmarish fever dream that ends with Reagan pushing a big red button and triggering an explosion, I never quite got what they were talking about.

As far as I can tell, children believing that a bomb could fall out of the sky at any second and humanity would either be totally wiped out or bombed back into the Dark Ages is a concept that really took shape in the postwar era, after the United States dropped Little Boy and Fat Man on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end the Second World War with a bloody exclamation mark. That was when the big bomb became a reality, and by the 1980s, as America’s leaders were talking tough to the Soviets, the end of the world felt like a very real thing. It would probably explain why when I was two, 100 million people tuned in to ABC to watch The Day After, setting a record for television films that still stands today. The world I was born into, it seemed, was going to be nuked at any second.

From a young age, I was consumed by dystopian and apocalyptic visions in my head after seeing that Genesis video. I’d lie awake in bed and think about it, what it would be like, if I’d even know it happened, if my family would survive, and what my little stretch of America would look like. I was five years old, and all I could think about was the end of the world. I was growing up with images of mushroom clouds dancing in my head, consumed by the fact that those “damn Russians,” as my grandfather (whose own parents escaped the country after one too many state-sanctioned attacks on their little village) would say, were going to strike at us, causing us to take reactionary measures, eventually filling up the sky over my suburb with missiles aimed to send us all down a road to nowhere.

Thankfully, the more I sat in front of the television, the more I was given an opportunity to form a better image of what things might look like in the postapocalyptic future. I was a child during the decade when the end of mankind was given its best look; the 1980s made the possible future dystopian wasteland look somewhat interesting, if I could somehow stick around to see it. Dystopia was everywhere, including a commercial break during Super Bowl XVIII and the iconic Ridley Scott–directed “1984” commercial with the streaking runner sprinting past a gray Orwellian background while being chased down by soldiers. She has a hammer in hand that she stops and flings at a screen where a Big Brother–like figure is talking to the broken-down masses. It was exhilarating to see, and although I didn’t really understand the meanings or allusions the commercial was trying to make, I was stunned by it. It was all so beautiful, the runner’s bleach-blond hair, white top, and bright orange shorts set against the stark and hopeless postindustrial setting. For some reason, I found myself liking how that dystopia looked.

“Dystopias are usually described as the opposite of utopias,” Margaret Atwood writes in her essay “Dire Cartographies.” When we think of dystopia, we think bad, we think something worse than death, we think all of our comforts leveled to the ground and all traces of human advancement turned to rubble along with it. “But scratch the surface a little,” Atwood goes on to write, “and—or so I think—you see something more like a yin and yang pattern; within each utopia, a concealed dystopia; within each dystopia, a hidden utopia, if only in the form of the world as it existed before the bad guys took it over.”

I was weaned on fashionable postapocalyptic futures and possible dystopias in my pop-culture diet. Cobra Commander trying to take over the world, only to be thwarted by G.I. Joe’s stylish army outfitted in synchronized blue uniforms, with colleagues like the very beautiful and rotten-to-the-core Baroness and the steel mask-wearing Destro, who had an air of regality about him even when he was trying to blow things up. They weren’t good guys who would do good things if their plan for world domination, which was explicitly mentioned in the show’s opening credits, actually took place. Of course, what they’d do once they took over the entire planet wasn’t explained, because little kids want action, not semantics. But a little part of me liked Cobra purely for aesthetic reasons (the handsome all-blue uniforms, the symbolism that I’d later realize was heavily influenced by Italian and German fascism).

My utopian visions set against dystopian scenarios kept popping up a year after seeing the “Land of Confusion” video for the first time. Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop, which is set in a Detroit that isn’t supposed to be too far off from 1987 when the movie was released, wasn’t scary, but I could tell it represented a society that had either gone completely over the edge, or was a hair from toppling over it. There are guns, drugs, and a dead cop brought back to life as a law-enforcing cyborg. He’s a walking mass of metal covering dead human flesh, and for a brief moment, he was the hero all the kids at school were talking about. But for me, the fascination lay in the city that was also a hunk of steel and metal with something rotting and dying underneath it. I wasn’t interested in the cop’s story; I wanted to know how the city got like that, and what it meant about the rest of the world.

By the end of the decade, I’d somehow find myself watching Escape From New York, Blade Runner, Terminator, and John Carpenter’s They Live, all usually part of some Saturday afternoon television lineup, or with a babysitter who rented the movie from the local drugstore. I didn’t have any idea of what a dystopia was, nor did I seek out any film that could be described as such, yet I was drawn to those movies and television shows, some of them crude even by 1980s standards. They helped me realize at an early age that the future is fucked no matter what scenario plays out, and that no two dystopias look the same. It could happen after we’ve become a more advanced civilization in terms of technology, or it could be right now, like They Live shows us. After watching that film, I started to think that we could all just be walking around being controlled by some group (otherworldly or otherwise), and we don’t even know it; that, to me, is dystopia, and seeing that film for the first time made me understand that. And no matter what, at the heart of many dystopian and postapocalyptic films from the 1980s, there’s a serious anti-authoritarian vibe given off by characters like Snake Plissken and Mel Gibson’s “Mad” Max Rockatansky, but there’s also lightheartedness to a lot of them. The films tended to be crude or low-budget because it just wasn’t the message people wanted to get. The end of the world, or the idea that we’re already living through one of humanity’s darkest hours wasn’t one we wanted to think about. Sure, there was the thought that we could go to war with the Soviets at any minute, but when you look at the counterbalance to that, the decadence and greed of the Reagan era, you see how much people wanted to avoid really thinking about any of that. How can you be bothered with the end of the world when you’re busy charging everything in the mall to your credit card?

Yet I paid attention, and now I feel like I’m actually a better person for being introduced to these worst-case scenarios at such an early age. Coming to terms with the inevitability that the world as I personally know it will one day end one way or another is something I dwell on in my quieter moments. But as I watch humanity march toward darker places, I’m comforted by the fact that, no matter what, a little light can always be found.