Fiction

What We Know

by Matthew Salesses

I tried to tell Rachel once, when she was just starting to speak, that she was adopted.

“What’s ad?” she said. She was going through a phase where she said only the first syllable of longer words.

I thought about how to explain that her mom and I were not her birth parents, that her birth parents had given her up, that we had paid for her. She was two.

I thought, This is the same as the stork that other parents describe. The airplane had been our stork.

“Daddy was adopted from Korea, too,” I told her, but by that time she had gone back to her dolls. My wife, Su Young, loved dolls and had furnished our daughter with an entire family of plastic.

Before Rachel came to us, I had insisted we tell her the truth about her birth. My parents, I believed, had been right to tell me, though they were white and couldn’t hide it, while my wife and I were adopting a child who looked like us. (Su Young was a native Korean and believed in racial conformity.) But the day our daughter arrived, I was struck silent. The woman paid to care for our baby set her in our arms, and Rachel’s pink face glowed even after the twenty-hour flight. “She is good girl,” the woman said, her only words to us. I think I read later that she wasn’t supposed to say anything; she went out of her way to offer this praise.

When Rachel was old enough to understand a little—five, I think—my wife reminded me of my plan. “Do you still want to tell her?” I had kept my first try to myself, since it had come to nothing.

“I don’t know anymore,” I said.

“I don’t think it’s a good idea. After what you said to your mom, that she wasn’t your real mom, that you wished your parents had never adopted you?”

I couldn’t imagine Rachel saying this to us, either. I would be angry; I had an angry streak. So we told our parents that we were not going to tell Rachel about her adoption. My parents didn’t argue. Su Young’s parents had wanted it to be a secret all along.

Rachel grew into a beautiful little girl with, somehow, Su Young’s cheeks—so people told us all the time. We mostly forgot that Rachel wasn’t our blood. My wife had a model’s high cheekbones and a baby’s puffy fat below; if she had grown up in America, she would have had her cheeks pinched constantly. I’d gotten into the habit of pinching Rachel’s cheeks, something I did even when she was a teenager.

I ended up having to explain about adoption after all, of course, as Rachel reached an age where she realized my parents were different from us. “Why are Granddad and Grandma so white?” she asked when she was eight.

I explained that I was born in Korea, and that my Korean parents didn’t want me, so I flew on a plane to America because her grandparents wanted me.

“Why didn’t your Korean parents want you?” Rachel asked.

In truth, this was a question I had asked myself, without asking myself, you see, my entire life.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Am I adopted, too?” Rachel asked. “My parents didn’t want me, too?”

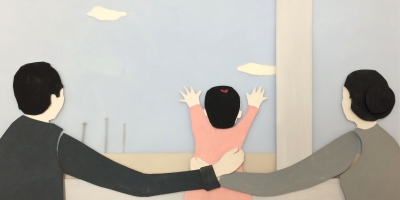

It might have been easy to tell her then, or at least easier. But I didn’t want her to feel unwanted—at least this is what I told myself later. I realized I had answered her poorly from the start. “Your mom and I are your parents. We’ll always want you. We will never let go of you,” I said.

I kissed her on one of her fat cheeks. “Ew,” she said.

She was that in-between age where sometimes she seemed surprisingly adult and sometimes still a baby.

My parents were wonderful with Rachel. My father was older, retired by the time we adopted, and he would drive the twenty miles to take care of Rachel whenever we needed. He would sit on our dark blue couch and bounce her on his knee, his skin whiter against the blue, her skin darker against his.

I often watched them like it was looking at a piece of my childhood. What complicated feelings had my father felt for me? More complicated because of our different races? Was he able to feel for me the simple acceptance that I felt for Rachel, that she was a part of me even when my wife had not given birth to her?

My father was aging quickly, and I worried that he would pass away on us. He had waited so long to marry, and we had waited to have a kid. I was more scared for Rachel than for my mom and myself, to be cut off even more from her past. She liked to tug his nose as he bounced her, which made me remember how I had thought my too-small nose was the only thing that kept me from looking white, like my parents.

It was my mom who died first, though, even with my father nearly eighty then. Rachel was starting middle school. My mom suffered an aneurysm—she worked herself to death, having refused to retire when she could have. She was the type of woman everyone knew, between the church and outreach programs and even the town hotline: she spoke on the phone with suicidal kids once a week. She had been a guidance counselor, though she had the PhD to be a shrink.

With the first pain of the aneurysm she had crashed her car into a tree—though the tree didn’t really do any damage. It was just a symbol. She had been on her way to a widow’s house with a casserole and some advice. She had felt something rupture and had slowed the car before it veered. “Our family was always full of bad drivers,” she said when we found her. She had called me for some reason, instead of 911. She knew she didn’t have long.

I called the ambulance, which got there just before Su Young and my father and me. We left Rachel at home, something I would later regret. She should have heard her grandmother say our family was full of bad drivers, one last piece of advice, and that she loved us all. But more than that, it might have helped Rachel to hear me apologize to my mom that I had ever given her a hard time about adopting me. I hadn’t known I was going to say that until I did.

My father would pass a few years later, when Rachel was in high school, with both my wife’s parents going in between. There was a lot of death in those years, and I think it made Rachel a darker teenager than she would have been. My father passed in the night. My in-laws died on a trip back to Korea, some shared disease, and we flew out for the funeral. They had wanted to be buried in their hometown, which at one time had also been my wife’s hometown. Rachel had seen it when she was younger, but the funeral trip was the first time she was old enough to really take in her heritage.

It seemed as soon as we got back that she started wearing her hair short and her clothes black and torn, as if everything about her had been cut up. She made a harder set of friends. My wife worried for her constantly—she would go into Rachel’s room and rearrange all of her childhood dolls so that they seemed to be throwing a party, something that used to make Rachel laugh but now got no reaction. My wife was desperate; I thought this phase was fleeting. We argued about our daughter night after night.

Su Young may have been depressed, too, about her parents’ deaths, so far from her. She had a complicated relationship with our birth land, nearly as complicated as mine. She still had ingrained in her all the strictures of a Korean upbringing, yet she had long rebelled against them, a rebellion that had started when she became an American teenager. That fight seemed to fade after her parents died. Maybe, I thought, that was why she took Rachel’s rebelliousness so hard—it was like a reverse of her own.

Now Su Young wanted to return to Korea. I even thought about retiring there, though I wasn’t going to mention anything until I was sure it was both doable financially and what she really wanted.

I was a believer in phases.

Rachel got in her accident only a few weeks after passing her driver’s test. I had made a stupid deal with her, that I would let her drive my car if she wore colors and grew her hair long again. She had stewed in her room, but there was a concert she wanted to go to. Finally she changed. I thought I saw my beautiful little girl again, though when I tried to pinch her cheeks she turned and said something under her breath that sounded a lot like “I hate you.”

Another car plowed into her driver’s side after running a stoplight.

If only, I thought, she had been thinking about driving instead of hating me.

At the hospital she was blinking, barely awake, her perfect cheeks bruised and expressive with pain. We cried as we told the doctor we were both blood matches, type B, and would do whatever we could. We had requested a child with type-B blood in case of just such an emergency. But the doctor stopped us before we were hooked up to her, as if he had forgotten something, and said with an appropriate confusion that Rachel’s blood was type A.

After our daughter’s life was saved by a stranger’s blood we watched her sleep and Su Young said maybe she wouldn’t remember. But I had seen the fear and misunderstanding in Rachel’s eyes, before she passed out, as the doctor hung the bag on her IV tree.

Of course this was after my wife had said many other things, but I still felt cold about her saying it, as if she valued life less than the issue of adoption. For a moment I almost wished Rachel would remember, but Su Young stared at her fists like two bombs in her lap. Her eyes were puffy, above her puffy cheeks. She was all puff.

“It was my fault,” I said again.

“It was not your fault,” she said again.

“She loves us,” I said.

“She loves us,” my wife repeated.

When Rachel recovered, she didn’t wait long before making us call the adoption agency. We told her the whole story. We would have done anything for her, and she knew it. We discovered after many calls to the agency that the woman on the plane had made a mistake. She is good girl, the woman had said—but she wasn’t supposed to be our good girl. “What does it matter?” I asked. Either way she was going to new parents.

“We love you,” my wife said, kicking me. “We are your parents. Nothing has changed.”

I could see she only hoped this. She didn’t leave me, which is something I’m still thankful for. I still blame myself.

Sometime after the accident and before we could forgive ourselves—maybe around the same time Su Young and I thought everything was as back to normal as it could get—Rachel demanded the address of the agency and of the hospital where she was born, and we found that she had been saving her allowance for years and had bought a one-way flight to Seoul. She was full of some inner force, which maybe she had never gotten from us. She found someone to give her a few brief Korean lessons, and she went in search of her birth parents. She was braver than I ever was.

I didn’t say this aloud, of course. Su Young was in meltdown. For her sake, I could never publicly root Rachel on.

“We could all go together,” I’d suggested at first. But that would have been a nightmare for my wife. To redefine Korea, in the absence of her own parents, by Rachel’s difference from us.

“Do you think this will be enough for her?” she asked me.

“She is good girl,” I reminded her. She sighed. She wanted an answer not from Rachel’s father but from an adoptee. I didn’t know how to explain the gap between what I knew and what I had always known.