Nonfiction

by Jason Diamond

Your teenage years are littered with things that you spend the rest of your life trying to understand, live down, or make sense of for yourself or others. I feel like I’ve moved past trying to get over those awkward years, the bad poetry in spiral notebooks, the awkward kissing, and the perpetual feelings of loneliness that stuck with me throughout high school. I’ve put those things in their proper places and don’t feel much need to revisit them, yet I still find myself trying to explain away the skinhead company I kept back then, to people and their misconceptions.

My teenage skinhead friends populate my memories like characters in a coming-of-age film, the movies where you can count on wistful scenes of naïve bad behavior, victimless petty crimes against the establishment, but also against proper comportment and etiquette, to show that innocence, like the good times, is short-lived. John Hughes’s 1986 film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off features one of the best of these scenes, where three of the film’s main characters—Matthew Broderick as Ferris Bueller, Mia Sara as Sloane Peterson, and Alan Ruck as Cameron Frye—wander the halls of The Art Institute of Chicago, looking at Kandinskys and Picassos, getting lost in the dots of George Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, and kissing beneath Marc Chagall’s stained glass. Hughes himself called the montage “self-indulgent” in the DVD commentary for the film, but I’ve long thought it to be his defining scene. Set to The Dream Academy’s glowing instrumental version of The Smiths’ “Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want,” Hughes’s quiet respite from the hilarity and chaos caused by a day of skipped school gently sums up both the blameless days of youth, and the realization that there is a great, unknown void that smacks you in the face immediately upon reaching adulthood.

I had days like that: I recall Sam and I, driving in the little beat-up 1972 MG MGB that he purchased for a song, and swore he’d fix up someday. The top is down, I’m sixteen, and he’s eighteen. There’s a boombox on my lap, and a cassette tape with Wilson Pickett’s greatest hits playing as we drive into the city. It’s a Saturday or Sunday—I know it’s the weekend, so we aren’t exactly breaking any rules, but it just feels good to be out. We’re looking for the spot where Chess Records was located at 2120 South Michigan Avenue, but we get lost because we don’t have a map of Chicago and are too afraid to ask for directions; instead, we settle on “jumbo” slices of pizza and Styrofoam cups filled with flat RC Cola.

All in all it was a good day, something to break up the albatross that was my day-to-day routine of crawling out of the pot of my rapidly decaying home life, into the frying pan that is high school for any kid. The daily trial by fire of trying to fit in while being myself, the teachers that I knew didn’t like me, and the other students that hated me for reasons I couldn’t understand. I look back now and realize that having something outside of that was what helped me keep going.

Another film that manages to capture this sort of spirit, while in a far less subtle manner, is the 2006 British drama, This Is England. The film’s protagonist, Shaun, a twelve-year-old boy whose father recently died in the Falklands War, befriends a group of rowdy skinheads who take the lonely boy under their wing. About fourteen minutes into the film, the energy building, there’s one sequence that leads into another, first where we see Shaun riding his bike, washing a car for money, buying and using a slingshot, then again riding his bike alone, a solitary figure on two wheels. It is a lovely and melancholic montage that reflects just how lonely youth can be. Shots of Nottingham (where the film was made) are almost pastoral in scope. This leads into the next sequence where one of the skinheads arrives outside of Shaun’s window, telling him he’s been invited to go “hunting” with the group. What follows almost looks like a Lord of the Flies adaptation by François Truffaut, as Shaun and the skinheads decimate abandoned buildings with glee, letting out their hostility towards an England that has let them down, and having a grand old time doing it, all the while dressed like ragtag, freegan droogs. Despite the violent nature of destruction, it’s a very sweet fifteen-or-so minutes.

“My parents were a bit confused at first,” Sam tells me about his Jamaican parents’ reaction to his earliest proclamations of being a skinhead. “But I think they began to understand…I was paying tribute to their roots, as well as becoming my own person.” It would make sense, of course, his parents’ skepticism, as people from the Caribbean islands, along with immigrants from all over who moved to England in the 1970s and 1980s, were constant targets for The National Front and other racist groups. When his parents moved to America, hate groups were recruiting skinheads in England, the tough image adding an intimidating edge to the hateful message, and the term “skinhead” suddenly meant the same thing as “Nazi,” even though the racist skinheads (at least in America) were in the minority. It no doubt looked odd to Sam’s parents to see their son wearing a t-shirt with “Skinhead” in Olde English lettering across his chest, considering that he’d be a target of that very group had his parents chosen to live with relatives outside of London, instead of Illinois.

Today Sam is a chef in California with a wife and two children, one he named Jordan, after Michael Jordan—the hero of all Chicagoland kids when I was growing up—and the other named Turner, after Tina Turner, his favorite soul singer. Sam and I keep in touch with each other over the internet. He randomly emails me things apropos of nothing, or to tell me he read something I posted on Facebook.

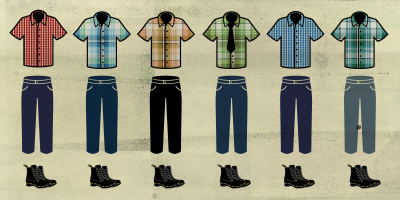

“It just looked better,” he tells me over email, about why he decided to shave his head and wear tight Ben Sherman shirts, suspenders, and Doc Martens boots. Sam tells me that after his Jamaican immigrant parents moved him to a predominantly white town, he felt “like a weirdo being one of the only black kids,” so he “started hanging out with the other weirdos.” Punks, goths, ravers, theatre kids—whoever would have him. “I liked the punks,” he says, “But I didn’t like most of the music.” Sam grew up on a steady diet of reggae, rocksteady, James Brown, and Motown, so naturally, “That’s the shit I liked.”

Skinhead culture grew out of the Mod subculture of the 1960s. For the working-class English kids who couldn’t necessarily afford the fine Italian suits and nice haircuts, hand-me-down tennis shirts, work boots, and shaved heads worked better. First known as “hard mods,” skinhead started gaining momentum as punk began to take off in the UK. Eventually there were bands filled with skinheads who played a faster, more aggressive style of punk that would be dubbed Oi!, but much like the mods, skinheads gravitated more towards classic American rhythm & blues, reggae, and soul music. “That sounded more my style,” Sam says.

I started hanging out with Sam more and more at the time when his style evolved away from the jeans and tight button-up shirts, and more towards the classic 1960s rude boy that came out of his parents’ Jamaica, adopted by English kids a decade later. He wore sta-prest slacks, black leather brogues, and a trilby hat. He looked better than anything else anybody was wearing. Fred Perry tennis shirts, black v-neck sweaters when it was colder, parkas in the winter; he was the only person I knew as a teenager who truly dressed well. “I dressed along the same lines until about twenty-two; but I always keep my head shaved,” the shaved head serving as a symbol of his coming-of-age, the subculture that helped usher him into adulthood.

Two years younger than Sam, I started tagging along with him just as he got his license, long drives to the South Side of Chicago to find Salvation Army stores, and sometimes northward over the border into Wisconsin, where we’d search garage sales always with the same purpose in mind: find records. Soul, gospel, and old blues 45s—Sam taught me to dig through dusty crates, ignoring my allergies to untouched vinyl and the dust that whirled upwards into the air. Sam showed me how to recognize the labels from the bigger ones like Stax and Atlantic, to Detroit labels that were dwarfed by Motown empire like Fortune and Revilot, all while flipping past useless soulless pop from bygone eras. You’d flip fast, and if you saw one of the labels or names you were looking for, if you came upon a record featuring songs by J.J. Barnes, Gloria Jones, or some other overlooked performer with a golden voice, it was like being a panhandler finding that one nugget of gold.

There were others: Sean, a 6’6” skinhead who had never thrown a punch in his life. I’ve always assumed a person of his size didn’t need to, but I felt that, if presented with a reason to, he’d probably decline to fight. Sean didn’t dress as well as Sam, but he drank Guinness, and gave me my first sip of the thick stout. Sean had some two best friends whose names are lost to memory, both of whom loved to talk about their “working-class pride” while wearing thin bomber jackets in the winter with patches sewed onto the back that read “Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice.” There were others; mostly men, a few girls (they called them “Skinbirds”), and Mike, who joked with me that he became a skinhead because his Jewish mother and African-American father passed down the most unmanageable head of hair possible, and shaving it off was the only thing he could do.

My first serious girlfriend was a skinhead girl, who was actually more of a goth when we started dating, but who became a skinhead in the time between our first break-up and reconciliation. She never asked me to shave my head or wear a pair of suspenders; none of the skinheads I hung around with ever expected any of that from me. Some of them actively looked for trouble, while others tried their damndest to avoid it. They knew people looked at them curiously, but they just went about their business, each having their own reasons for adhering to that single style and subculture.

Today you walk past a Doc Martens store, and the brand is proudly proclaiming their connection to the movement with vintage-looking pictures of skinheads wearing their boots, while companies like Ben Sherman and Fred Perry routinely do the same. It isn’t necessarily that skinhead has gone mainstream or is accepted, but like any subculture, it’s rebellious, and rebellion sells. And although some still remain, eventually, after a bit of explaining, Sam’s parents came to understand that racist skinheads are just a part of the culture’s strange ecosystem, that their son wasn’t crazy. “I think they thought you were weird, because you were my one friend that wasn’t a skinhead,” he says. “I guess they’d gotten used to it by then.”