Nonfiction

Bridging the Gap

A Queer Talk with my Religious Aunt

by Eric Anthony Glover

The idea was simple: Find someone who disagreed with gay marriage and actually listen to them.

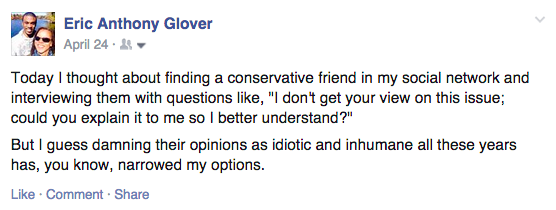

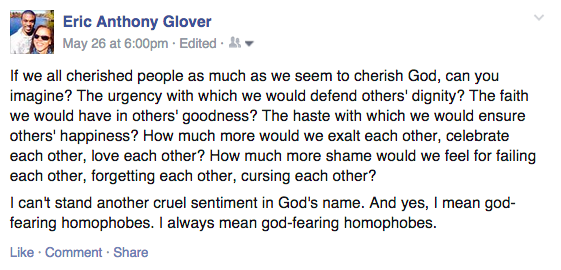

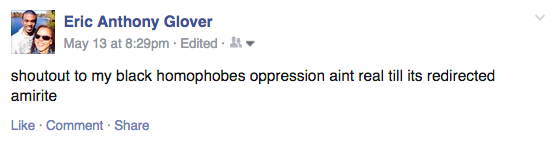

Interviewing a family member was the easiest way I could think of to engage with someone against my rights and remember their humanity while doing it. In the years since I’d come out as queer, I’d gotten faster at forgetting that I, too, had once been a Christian against marriage equality. After I broke from the faith for my own sanity, what started as sadness over my sexuality became something more seething toward the conservatives I’d left behind, resulting in statements like this:

Clearly, I’d needed a one-on-one with a living, breathing religious conservative against queer rights for some time—if only to remind myself that there are faces to the faith and heartbeats behind the homophobia. I figured I should spend the interview focused on listening rather than debating—not my forte with this issue, but oh well—and for goodness’ sake, find some common ground.

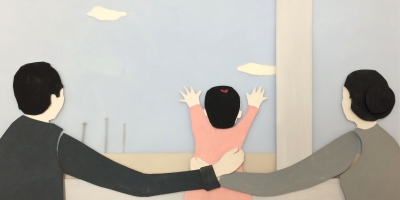

Lucky for me, despite all the earfuls I’d given just about everyone about how unethical homophobes are, I drew a line at disowning the ones who were blood relatives. That included my aunt Jackie, with whom I’ve had an excellent, loving relationship my entire life. She heard that I came out a couple years back, although she and I never had an in-depth talk about it. Her son, Brandon, had come out as gay well before, and he took me under his wing as I found my footing in the queer community. This past May, Brandon proposed to his long-time boyfriend, Oskar. Although I was ecstatic for Brandon, it troubled me to hear that Aunt Jackie likely wouldn’t attend his wedding on religious grounds.

However, if there was anyone with whom I might be able to broach a contentious topic, it was Aunt Jackie. I emailed her for an interview, convinced I’d found the perfect candidate to translate right-wing ideology into something that made sense to me. And as I began to question her, I felt a step closer—for once—to regaining a genuine understanding of the good intentions behind conservative logic.

I just didn’t count on her asking me questions back.

Eric: Thank you so much for doing this at all. I know it can be a prickly topic.

Jackie: Of course, Eric. You know, I was a little bit hesitant because I wasn’t sure of what you really had in mind. But I think we probably need to have this conversation.

Eric: Yeah. I didn’t want anything super emotionally charged. Just an intimate, chill talk.

Jackie: This’ll be good for both of us.

Eric: Tell me about your son Brandon.

Jackie: Brandon is someone who looks for truth. He’s an honest person. He’s very accepting or tolerant of whatever differences there are in people. He just accepts people as they are. He usually never speaks negatively of anyone. He always tries to take the high road.

Eric: How did he perceive homosexuality as a child?

Jackie: Well, I would say that based on Brandon’s experience, he had an idea that it would be probably be unacceptable. Since he wasn’t open about it. He did date girls. I don’t know if that was a way of probably trying to not be [gay]. Or maybe just doing what was expected.

Eric: Did you ever suspect him to be gay?

Jackie: I remember one time, asking him. And he said no. And I was just very happy that he said no.

Eric: What were you prepared to say to him if he said yes?

Jackie: If he had said yes, I don’t know. Probably what I said when I did find out. I had a lot of questions. “Are you sure?” “Have you talked to anybody?” “What about your faith?” “Do you believe that it’s a sin?” And he explained to me how he had struggled with it. I remember him saying, “Don’t you think that I have prayed about this? Why would I choose to be subject to being something other than what people would call normal?” Or something to that effect.

Eric: What was your reaction when he said that?

Jackie: I was sad. Just the thought of my child having to struggle with something so heavy. Alone. And to wear the mask. And people always say, “Well, when are you going to get married?” “You got a girlfriend?” Just imagining what must have been like. I didn’t feel sorry for him, but it just made me sad.

There was also the guilt. Was it something that I missed? Could I have done something differently? All kinds of questions go through a parent’s head when they’re faced with that.

Eric: Why was being gay something that you wanted to prevent in Brandon?

Jackie: Why would I want my child to be subject to the meanness of people? The risk of being physically harmed because of people who have no tolerance of anything outside of their comfort zone?

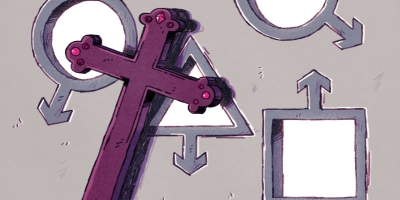

Then, there’s my belief that homosexuality is a sin. I want Brandon to be happy in this life. But more importantly—this is just a short period of time. We’re all going to spend eternity somewhere. And if his homosexuality is something that might stand in the way of him seeing God, then of course that’s something I would want to change.

Eric: How do you think Brandon feels when you tell him that homosexuality is a sin?

Jackie: He told me that he and his fiancé, Oskar, were engaged. I asked him how he reconciled that with his faith. I said, “If you can show me that…” And he said, “I can’t show you that.” Because the Bible defines marriage as between a man and a woman.

Eric: So when you asked him to “show you,” you were asking him to tell you where in the Bible there is justification for gay marriage?

Jackie: I knew that he couldn’t show me. But it wasn’t a trick question. I wanted him to help me to understand how he came to this decision.

Eric: But Brandon did not offer an argument that could religiously justify his decision to marry Oskar.

Jackie: No, he didn’t. But he sent me an article to read. Although I chose not to discuss it a lot with him.

Eric: Why’s that?

Jackie: Because I felt that he had pretty much made up his mind. I read the article, and I could have given him all the reasons that I was not in agreement. But I don’t need to do that to him. I need to be supportive of him. And show him that whatever his decision is, he’s still the son, the Brandon, that I love. And if Oskar is the person that he has chosen to spend the rest of his life with, then Oskar is a part of my life as well.

Eric: So you’ve met Oskar a few times now, right? What was your first impression of him?

Jackie: I found him quiet. Very polite. There are some qualities that I do admire in him.

Eric: What observation would you make about Brandon and Oskar’s relationship?

Jackie: I think that they love each other. I think that they’re both on the same page as far as their faith. A good, caring relationship. They run together. They take care of their three little ugly pugs; they’re just as cute as they could be. They have a nice place.

Eric: I’m curious about whether you will be attending Brandon and Oskar’s wedding this month.

Jackie: Brandon has not given me the details of his wedding. I would first have to be invited, right?

Eric: If he were to invite you, do you think you’d go?

Jackie: Probably not.

This is where I am: I’ve come to a point of acceptance. I have accepted that Brandon is gay. And I have accepted that Brandon is planning to be in a relationship with Oskar. I don’t approve of it. But I have accepted that that’s the truth of his situation. So if I want to be in a relationship with my son, then I have to at least come to a point of acceptance. And I can’t imagine there being anything that he could do that would keep us from being in a relationship with each other.

They can celebrate the wedding better without me there. Without feeling that someone’s there who doesn’t approve. They can just be their natural selves, and not have to worry about me being offended or uncomfortable. That’s what I want for them. This is about them and their day. It’s not about me.

I’m assuming you see same-sex marriage and homosexuality as being opposed by Christians.

Eric: Yes, for the most part. That’s right.

Jackie: But are there not people outside of the Christian faith who are unaccepting?

Eric: There’s no attempt on my end to single out Christianity necessarily. Monotheistic faith has traditionally worked to ostracize people like me. And I’m only focusing on Christianity because I know that you are a follower of Christ.

Jackie: I don’t think that you’re targeting Christians. I hear a lot of [your] criticism…and I think it’s a matter of someone trying to tell me, “If you don’t think like I think, then we’ve got a problem.”

And my thought is, I’m not dismissing you. You said you didn’t want to dismiss people that you cared about. And I thought on that. Why, if someone that you care about doesn’t agree with you, would you dismiss them?

For my next piece, I’d like to return to the subject of being a man who likes men, but from a new angle. Sometimes I worry I’ve created too liberal a bubble around myself to fully understand conservative views or empathize with the people who espouse them. Which is dangerous. Living in a largely unchallenged echo chamber not only prevents me from growing—it allows me to flirt with dehumanizing people who disagree with me. And since I have family members who do, I think it’s time I seek out ways to start connecting instead of just condemning.

Again, this would be no effort to dehumanize you or any other Christians with conservative values regarding LGBT people. This interview would simply be an effort to bridge the gap between me and another person I respect—so that I might get a better grip on where my opposition comes from and how to better recognize why it’s happening at all. Without conversations like this, I feel at risk of dismissing conservative views on my sexuality as incomprehensible—and maybe with some open, compassionate discussion, that can change.

Please consider this interview for me. I’d love to hear what you think.

Best,

Eric

Eric: So the fact that I even brought up that I might dismiss someone who disagrees with me rubs you the wrong way?

Jackie: I took offense to that. When I read that I thought, why would you dismiss someone because of that? And then I went to your Facebook page. And I read it. I didn’t feel that you respected people who are Christians. And you sort of put everybody in one little boat. And you’ve come to the conclusion, “The hell with you. If you can’t get on board, get off the face of the earth or get out of the way.”

Eric: Do you remember anything in particular that made you feel that way?

Jackie: I read the part about the love, and the respect, and I think you end that comment with… “If Christians acted like that.” Something to that effect.

Jackie: If you get angry and see me as a person of poor character, then I would still hope that I would be able to respond to you in a decent way. That I’m not gonna kill you on a blog. Or on Facebook. I want to show a little bit of compassion.

Eric: You feel like the things you saw on my statuses were not compassionate.

Jackie: I feel that you stereotype people.

Jackie: What has your experience been that you have come to such strong feelings?

Eric: It’s a lot, Aunt Jackie. I could go on forever. And it’s not just the big stuff. It’s not just Dad using the word “faggot” around me after he heard about my sexuality. It’s not about hearing the word “faggot” everywhere. It’s not about me walking down the street and being told by some stranger that I look abnormal holding my boyfriend. It’s the small stuff. It’s knowing that people as decent and wonderful and caring and loving as my aunt would probably not attend her son’s wedding because a book told her not to. It doesn’t directly affect me, but when I talk to Brandon, I can see, “Okay, that was really hurtful.” When a conservative, for the thousandth time on television, says that I’m an abomination, and that I don’t deserve to be treated equally, it chips away at you. It chips away over the years.

When I hear anyone say that homosexuality is wrong, I don’t think it employs love, logic, or empathy. It’s something that I’ve struggled with for a long time, because when I think of what people do that’s most harmful…I think of killing; I could explain to you why killing is wrong without using God. I think you could explain to anyone why stealing is wrong without using God. I think you could explain to anyone, without using God, why lying is wrong. Why cheating is wrong. If you didn’t have religion, Aunt Jackie, I feel like you would be able to say why most wrongs we commit against each other are wrong because of their nature.

Jackie: There is a moral law, but in addition to a moral law, I have a faith that goes beyond it. I hear everything that you’re saying. And I’m not disagreeing with any of the conclusions that you have come to. But for example, you said you believe that it would be hurtful to Brandon if I did not attend his wedding. I don’t think that it would be hurtful to Brandon. If Brandon said, “Mom, I really want you to come,” I probably would come. I think you’re missing Brandon’s feelings on this.

Eric: I don’t know, Aunt Jackie. I’ve talked to him.

Jackie: Yeah, I think you’re off. I know you’re off.

Eric: So if he’d said, “I really want you to be there,” you would show up.

Jackie: What Brandon has said to me is that this is about him and Oskar. Making a commitment before God. And being joined in a civil union. He said it’s not about making a statement. It’s not about me being there. Now, I don’t know what Oskar wants. Oskar may be hurt. But I don’t think that Brandon would be hurt. I don’t have anything to go by other than what he would tell me.

Eric: I want you to remember that earlier in this conversation, I asked you whether you would show up if he asked. And you said you probably wouldn’t. Do you remember saying that?

Jackie: Yes. I did say that.

Eric: So Brandon knows that’s how you feel. I know that’s how you feel. And that probably affected his decision as to whether to invite you or not.

Jackie: Trust me on this one. If Brandon truly wanted me to be at his wedding, he would say so. We’ll agree to disagree on that. But let’s go back to how my decisions about Brandon affect how you feel about me. How do you feel about me saying no to Brandon?

Eric: If a Bible weren’t involved, I think you’d show up—

Jackie: But the Bible is involved. So speak to me on that.

Eric: I think…I think that you love your son. And that you want him to be happy. I guess… It’s just…

Jackie: I want you to be honest. I don’t want you to temper what you would say because it’s me.

Eric: …

Jackie: Because this is really the conversation that we needed to have. The questions have been about my relationship with Brandon. But isn’t it really about your relationship with me as a result of our having a different opinion of whether homosexuality is wrong?

Eric: …Yes.

Jackie: Yeah. So we’ve been going through the motions and not being honest about what the real point is. If the Bible tells me that stealing is wrong, murder is wrong, homosexuality is wrong, you would be okay with me saying that stealing and murder are wrong, but not with me saying homosexuality is wrong. So you’re being selective. And you’re trying to hold me to what your standard is. Even though according to what I believe, all three are wrong.

Eric: If you felt like stealing was wrong, and you attributed that to your religion, I wouldn’t care. At all. Because that has to do with how you treat people.

Jackie: You just care about the ones that will affect you.

Eric: Uh—more than me. But yeah, in this case, I suppose.

Jackie: Now, how I feel has no impact on how I treat you.

Eric: Okay, that’s exactly where the disconnect begins. That’s exactly where it starts.

Jackie: Wait a minute. I’m talking about how I treat you specifically.

You can say that you and [your boyfriend] Rob are going to be married, and invite me to the wedding. I could come to your wedding, but still not approve. Have you changed how I feel? No. So my showing up at your wedding still doesn’t mean anything because I have not changed how I feel.

Eric: But you’ve showed your support in that situation. You’ve showed that it’s more important to you that I’m happy than it was for you to prove some kind of moral absolute by staying home and boycotting.

Jackie: Again, it’s difficult to have this conversation when we’re not on the page about our beliefs.

Eric: Yes.

Jackie: To believe that homosexuality is a sin. You see that as immoral.

Eric: Yeah. I do.

Jackie: Explain to me how.

Eric: I think sins—when the Bible’s getting it right—are about telling people not to hurt other people.

Jackie: Wait, is there any part of the Bible that you believe? Because if you don’t believe the Bible, then why are we having this conversation?

Eric: It’s so frustrating that that’s the case. That the conversation ends with, “Well, I have my faith.” Then all of the common ground that was possible—

Jackie: I know you have read the Bible—

Eric: Plenty.

Jackie: Are you saying that the Bible does not list homosexuality as a sin?

Eric: That’s not what I’m saying. It does.

Jackie: But you are in disagreement with the Bible.

Eric: You got it.

Jackie: Just explain to me how you have come to the conclusion that because the Bible says it’s a sin, the Bible is in error.

Eric: If it’s not hurting anyone, if it’s actually something that has to do with love and compassion and being good to one another, it shouldn’t count as something evil.

Jackie: If it’s “not hurting” anyone… So that’s your definition of sin.

Eric: Well, you use the word “sin.” And I use the word “wrong.” The fact that I’m with Rob… I could tell you about the last nine months and tell you nothing about jealousy, hurt feelings, malice, evil. None of that would be involved in how I describe my relationship with my boyfriend.

Jackie: That’s possible in any relationship.

Eric: But what makes what I have with Rob evil? Inherently? That’s what no one can answer. There’s no argument that actually wraps that up. All I hear people say is, “It’s what God said. It’s what the Bible said.” That is not an argument. Rob and I love each other. We’re good to each other. We’re kind to each other. There is no evil in that. And there is no argument against what I just said. That should disturb you. That should disturb anyone.

Jackie: I hear you and I understand what you’re saying. I don’t agree.

Eric: Why don’t you agree?

Jackie: I believe that God’s standard is different from man’s standard. Over the course of ages, standards change according to the culture. But I believe that God’s standard does not change. Now, I’m not gonna debate—and I’m not trying to end the conversation. But I do know that we don’t benefit from going back and forth.

I understand what you believe. You believe that your relationship with Rob is a loving relationship. There is no evil in your relationship. And for that, I am very grateful. I do hope that you can be happy in your relationship with Rob. Do I agree that the relationship is approved of by God? I believe—and I’m not even gonna say it because you told me you get so tired of hearing the same thing, so—

Eric: No no, that’s fine.

Jackie: You’ve already given me the absolute. The absolute is that there is no argument against what you believe. If there’s no argument… We just talked for a long time. Hopefully, you’ve learned some things about me. Like you said in your original email, hopefully, we will still be okay. I’m hoping that you will find a way in your compassion, and love, to be able to still be in a relationship with me—not dismiss me.

Eric: Yeah, of course. That’s never gonna happen.

Jackie: Basically, what you’ve said is that, there is no room for argument to deny your relationship. You said that it’s showing a lack of love. I disagree, I disagree, I disagree.

But I love you. And how I choose to treat you—I’m hoping is the same way that you would treat me and other people who may not be in agreement with you. I hope that you aren’t coming to a place where you dismiss people who may not be in agreement with you on this or on other things.

Because there isn’t just Eric. There is a whole big world and a whole lot of people that are living every day with a whole lot of issues, and that’s just one of them. I have three little boys that I see two and three times a week. And they’re in a totally dysfunctional family. They are misrepresented in the school system. And as important as this conversation is, I’m concerned about them being able to just grow up, get an education, and not be a part of the system or statistics.

Eric: That’s very important. They’re just not mutually exclusive. The fact that people are discriminated against because of beliefs that you espouse… That causes things like teen suicides. That causes things like adult suicides. That causes people to be paid less or fired because they’re gay. Or not hired because they’re gay.

Jackie: But Eric, it’s not limited to gay people.

Eric: No, but that is an ill that needs to be stopped. That is one of many evils perpetuated by people who say they’re doing good. I’m not saying that my problems are necessarily the most important, or exclusively important. It’s important along with a lot of other things. Dismissing what LGBT people are going through, the violence that they suffer, the mental distress that they suffer doesn’t show a lot of love.

Actually, there’s a couple more things I want to say to you. I want to make it clear that it has nothing to do with respect, because I told you in the email, I’m telling you now, that I respect you, I love you, I think you’re wonderfully intelligent and compassionate—that’s not going anywhere. That’s not even at risk. There will be no dismissing you. Period. Ever. You’re my family.

“I don’t agree” is not an opinion that exists in a vacuum. It creates a culture that does actually kill people. That does cause them depression. That makes them feel like they’re second-class citizens. You can tell me all day that the Bible justifies this and justifies that. The Bible has also justified some really terrible things—that maybe you don’t agree with now, but at one point, someone was saying what you’re saying to me. Almost exactly. But this time about race. Someone was saying miscegenation is wrong because the Bible says X, Y, and Z. It’s something that people have actually believed. And thought there was a spiritual, higher, moral truth too. That God mandated. They believed it just as much as you believe what you’re saying right now. That saddens and scares me. Because that creates a chasm between people that can’t be bridged.

When God becomes the stamp with which you disapprove of something, and no reason can reach through to you about it, it causes things like, “Well, if Brandon doesn’t want me there, then I guess I don’t have any responsibility to go.” Brandon hasn’t asked you to go because he knows you’re going to say no. Or he thinks that. And you’ve given him that impression.

It’s not as simple as, “Eric, I believe in this corner that homosexuality is wrong.” How you feel, added up to how other people feel about it—which is a lot—has caused a lot of damage. A lot of damage. It gets people killed, it gets people depressed, and it keeps people in second-class citizenship. And I think that you can be a lot better than that.

Jackie: I appreciate what you have said. And I’m glad that we had an opportunity to talk.

Eric: Yeah, me too.

Jackie: All right, sweetie. It’s 11:30.

Eric: Okay.

Jackie: Is there anything else?

Eric: Not now.

Jackie: All right. You have a good night.

Eric: I love you.

Jackie: Love you, too.

Photo by Ceci B Photography

Brandon wedded Oskar a day after the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage—and three weeks after my conversation with Aunt Jackie. Outside of a few texts, I hadn’t spoken to her since. But the stubborn optimist in me couldn’t help hoping, for Brandon’s sake—and for mine—that some of what I said had resonated. That when push came to shove, the regret of not being at Brandon’s wedding would be too much to bear after all. That despite all the determined dogmatism, my aunt would want to share in the happiest day of his life.

Of course, she wasn’t there.

I wish I could say expecting her absence took the sting out of it. It’s not as if the wedding wasn’t whole or joyous on its own. Brandon and Oskar’s ceremony—a small, soulful thing, candlelit and carried out with tenderness—was a tearful testament to true love, and certainly needed no sanction from straight people to feel authentic.

But sometimes, when I look back on it, I remember the price of being queer. I’m reminded that one day, I’ll have to prepare for those who want to attend my wedding—and likewise, prepare for those who refuse.