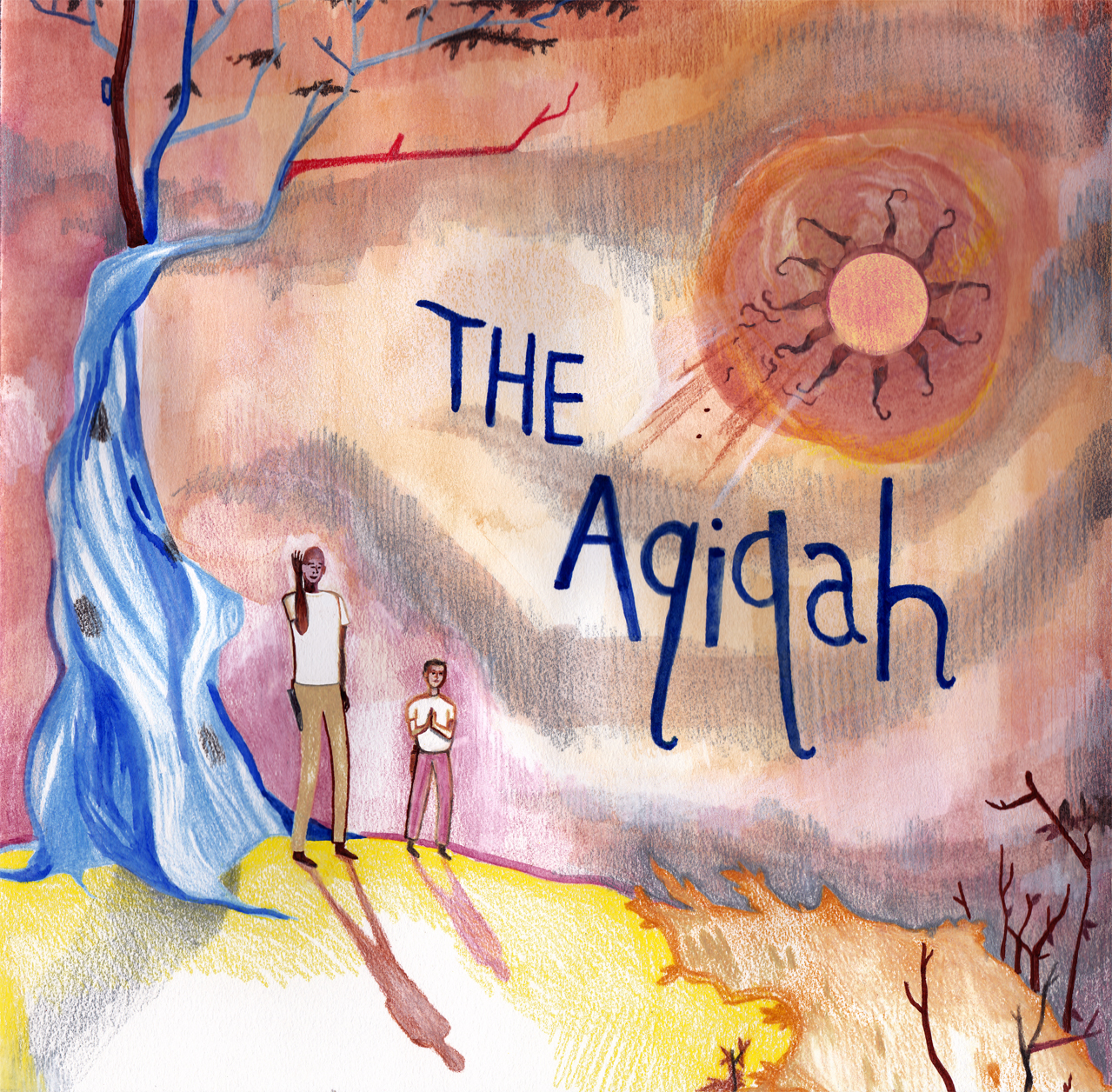

Nonfiction

by Kima Jones

I.

Connie married the African one afternoon in a not-white dress, her nails polished, probably gold, her modest diamond and our father’s teary face. His youngest daughter and the hard-working man beside her. The prayer rugs and prayers said. For mercy. For fertility. For ease. Her wide face and the mascara lining each lash. Our father and the several goats killed. A lamb. Our father and his to-be son-in-law trampling into the woods together to choose from the grazing beasts. To rub their animal backs and pat at the place where rump turns to tail. To watch the sun shift and make the afternoon prayer, Dhur, in the wood with the beasts. Where the older man has always led the prayer in his home, he cedes to this younger son in the woods. His right hand cupped behind his right ear the young man sings out, Come to success! Come to prayer! and the animals do not startle, they do not run, they remain in their grassy spot, all four legs tucked beneath them and listen to the two human men, one old, one young, pray for forgiveness, pray for the surety of a steady hand, pray that when they turn to the animals they find the thinnest length of skin at their necks from which to strike from. And the several goats and the lamb raise their heads. And then they are mounted. An able hand held under their chins. And when their blood is spilled and they are gutted on the floor of the woods, when their organs and intestines are discarded and their bodies tied at the foot and bound to a sport utility vehicle, the old man and the young man say, Allahu Akbar! And when my sister is presented as a wife instead of a daughter, every soul that bore witness, every hand that clapped, is roused to its feet and when the Imam said, Takbeer! they answered, Allahu Akbar!

Connie married the African who had crossed an ocean to get to her and worked days and nights and weekends in a factory spinning fabric and separating t-shirts and finishing the ends of curtains, living in a bachelor’s apartment with his cousins and uncles and brothers. He ate what he had and didn’t eat what he couldn’t. He brought Connie little gifts he found, others he bought. Dresses. Smooth stones. A bag of Spanish oranges. An electronic Quran. Crossword puzzles. A diamond ring. Later, a gold band. Later, a leather sofa. Later, much later, train tickets home to visit us. Visits I did not accept. My sister, my little sweet sister, swept up in the balloon of her first romance and at once married and making a home with a man. Our father’s new son. The frozen wedding cake in her freezer. The dress, beautiful, hanging in its plastic sleeve, at the back of her closet.

I have never seen the dress. Or been to her home. Or seen the small appliances she’s since accumulated. The inside of the microwave where she heats her husband’s food or the TV they enjoy together before bed. Her duvet or house plants. Her frying pans hung or housed in a wooden cabinet. The cereal boxes atop her fridge or whether the bread bag is tied or knotted. Never a glass of water from her kitchen or rest against a chair back. I’ve never lounged at my sister’s and seen a brother-in-law home from work. A key in the door. Does he kiss her on her cheek or her lip? Does she rush to him or call to him? When his coat is removed and hands are washed. After he has taken the train to the train to the bus to work and then home. When he climbs over her back as not to disturb her in the mornings. When he puts on each boot and a sweatshirt speckled with the remnants of work he found: painting a bathroom, tiling a floor, tarring a roof, hauling cracked bricks. When he left Senegal and crossed an ocean to get to her. When he left his family’s compound with a picture of Connie in his pocket. When he stood for the first time in New York and climbed out of the subway to find the rest of the world. When he first prayed, small toe to small toe, with the other men at the mosque to ask for a wife. When he left his mother, seated in her favorite chair, cupping her aged face, knowing when he returned it would be for her funeral rites. The field where he first kicked a ball and the soda stand where he first understood sex is a thing that happens, first, with eyes. When he sat in our father’s living room to court his bride and learned the ways to make her smile. When he holds one hand to his chest and bows his head to say, sorry, when his English is not enough. When he has excused himself from English arguments. When he has understood my English. When I have used HIV and AIDS and WAR and UNCLEAN WATER and FAKE VISAS and TB and POLYGYNY and CITIZENSHIP against him. When my sister and father have begged me to stop my mouth or cut my tongue from it.

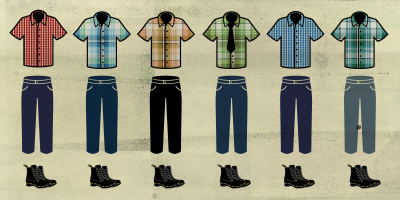

That beneath dermis but before bone, lived in me fear of the Black African. Those infomercials. Those charities. Those bony children and their mosquitoed skin. The Congo! The Jungle! Those men who raped and removed breasts. Those old, misshapen women who held down a bucking girl and cut her feeling thing from in between her. Those men with short pants and open shirts and scarred faces and long machetes. Those child soldiers turned pot bellied soldiers who held a gun to your head and made your family watch. Your family who later banished you. For what did I know of Africa that wasn’t merely an extension of my parents’ Afrocentrisms? That wasn’t as shallow as a first name and its meaning? ( Is Kima Kiswahili?) That wasn’t as cheap as the brass bangles about my arm? That wasn’t as hollow as names and dates memorized in class? That wasn’t as empty as the transparent conviction that Africa was a lived, tangible notion inside of me by proxy and therefore I understood and therefore mine was a knowing. Wasn’t I learned? What odious hubris when a brother-in-law stood in front of me and I refused to see him.

When my sister wedded him and bedded him, when he fed her the slaughtered goat, stewed, as their first meal, when our father prayed behind him. When he went to work before the sun came up and returned long after it set. When he saved money in a glass jar and called it new beginnings.

I reduced the man to a continent, to a horrible story, to a thing one survives and holds children close to warn them about.

II.

I was married under the moon of Ramadan, the holy month. My father presented me to my husband in a blue dress. I wore a borrowed ring and Connie stood beside me. I was married under the moon of Ramadan, the holy month, on my birthday. My wedding cake was thusly a birthday cake filled with pineapples and cream. We did not eat much of it. I was married under the moon of Ramadan, the holy month. Having fasted all day, birthday cake was too rich and sweet to eat. Most of it wasted, my name, absent of my husband’s, in bright blue script.

I tried for a baby and Connie tried for a baby and each, in our homes, in our marriage beds, with our husbands under us or behind, we prayed the prayer, slept with sperm inside of us and did not wash the lovemaking from our bodies till day. And when our husbands went out into the world, we swept our small homes and watered our little plants and read and read for methods. We ate sweet potatoes, we drank tea, we exercised, we lost weight, we demanded our husbands on top and we brought our knees into their chests and we prayed the prayer. We ticked off months and cried the losing cry when the blood returned. We threw away panties and wrappers and we lied. We called the old aunts and they lit the special candles. We fasted Ramadan with the baby prayer in our mouths. We stood before our mirrors and stared at the blue veins of dropped breasts and imagined a child’s head. We wondered the imaginary head hair and features, if they would sleep through the night or rouse at every stirring thing like their restless, wakeful fathers.

Connie became pregnant, but my belly did not grow of child but of wild. And where her baby attached to her and sucked the life source, dormant things grew in me that only fed to feed again. And where her skin smoothed with life, mine grew sallow of contempt. And where she could no longer bring her knees or forehead to the floor in prayer, I made rakat after rakat in empty servitude—bargaining, reasoning, demanding. The single prayer I said was the baby prayer, the fastening prayer, the mooring prayer, the prayer that said I deserved more than what was received.

I tried for a daughter in the bluest hours of the night. When the whole Earth was stilled and even my sleeping husband dare not stir. When the animal scratches of the city were muted and no siren, no street lamp, dare disturbed me. When tests were taken and exams reviewed. When the young nurse held the little cup of water to my mouth and begged me to take deeper breaths and then drink. When the results said never. When my husband buckled me into the car and held me close and then not at all. When there was a blood test and then another and more until each tube, each bloody tube came back and said never, never, no. Before my husband’s boot but after his palm. The lion’s share of blows to my back. When the door was locked against my husband, how many times did I call out for my father, call for him to come rescue his first daughter, how many times before I opened the door to be eaten by my husband’s mighty shadow?

It was then I prayed, on my knees, for a daughter.

Because oldest sisters get married first and have babies first. Because it was my birthright to have my baby first, my husband first, my little blue house, first. Because oldest sisters pass down dresses. Because oldest sisters pick over and take from. Because oldest sisters expect to have what they’ve always been given. Because my birth meant our parents had to stay together. Because I washed the dishes and took out the trash and went to school and cleaned up after the sisters to follow. Because more than a nephew, a child. Because more than a niece, my own. Because before doctors said no, the prayers went unanswered. Because before tests confirmed I couldn’t, the praying mouth went silent. Because more than a prayer, morning vomit, tender breasts, a firm uterine lining, a bassinet. Hadn’t Cain killed Abel for less? Or the same? What was owed to him by the plain fact of his first birth.

There are seven years between me and Connie. Seven years and two husbands and a father who chose sides. Seven years and two weddings and two marriage houses and two wedding cakes and two wedding rings. There are seven years between me and Connie and a mother and a stepmother, our several siblings and the several houses we grew up in. There are seven years between me and Connie but always the room we shared, the bunk beds we shared, the paint and its walls and secrets we shared. Seven years but the same face on her face as mine, a tribute to our father. There are seven years between me and Connie and the whispers we fashioned. Seven years and the skipping rope we used to jump, seven years and the hole through her left hand, the rusty nail she did not see climbing. Seven years and her neck craned into the sink for me to wash her hair, her weekly plaits, the beads and barrettes. Seven years and Connie walks on her tippy toes, but I am flat-footed and heavy. (The old aunties said, That one will dance! That one has mouth!) Seven years and our other sisters and our brothers and their own pairings. All of us, but always me and Connie. Despite the seven years, this younger, younger sister, always, always me and Connie.

Alone, my sister miscarried in her second trimester, in the morning, her husband having just stooped his head to enter the bowels of the subway, a sudden urge to toilet, a hand on her stomach and another on the sink for balance. A city bird on the sill looking in through her barred window. Connie would have forsaken modesty, on her knees, in front of the bowl, sifting through piss and blood and shit for the dull thing afloat. It never knew a material particle outside of her body. Not oxygen. Not light. Not cold. For all of Connie’s grief, her bloodied thighs, her emergency room and stay. For the afterbirth that would not come on its own. For all of our father’s rush down the highway, for all of her husband’s travels back to the bus to the train to the train, I was assuaged. In Connie’s grief, a little light. In her failed attempt, salvation. My sister’s child was dead, so I still had a chance. That a thing could live and die in a day and pass through a body like a drink of water. That a younger sister’s body would make milk for a dead baby. That an older sister would feel, however faintly, relieved.

Our father and his son-in-law went back into the woods, once more since the wedding, past the remaining goats and lamb, past the running things, with shovels and dug a human hole for the dead boy. They washed and perfumed the boy. Shrouded the boy. His father climbed into the human hole and made a first bed for the boy. They covered the boy with dirt and patted the earth flat. No marker. No sticks. No stone.

III.

Connie’s daughter was born, this first niece, and like all first things she was named, second-named, nicknamed, and everyone journeyed not long after her birth to say they witnessed that she is remarkable, and a blessing, ten-fingered and ten-toed, round head, a good head, a baby who latched without trouble or fuss. In the name of first things, all of the animals slaughtered. The multiple preparations of meat. The meat so tender and hot oil and steam released with each bite. The rose water and discarded soda cans collected in a giant plastic bag tied to the door knob. My father lived long enough for sons and daughters and now grandsons and a granddaughter so content he looked holding the sleeping child. And the young mother cooing into her daughter’s face. And the Imam’s prayer, the honey placed on the baby’s tongue to ensure her words will be sweet. The first daughter passed from aunt to uncle to cousin to friend, a blessing whispered in her ear, a kiss to her baby forehead or baby hand and passed to the next relative of outstretched arms. The old aunties hold longest. They call the first daughter by all of the names she will ever be known so she will always be able to recognize herself. They force her awake and they force her to cry. They praise God for her lungs and her scream and her little bleating tongue. They praise God she is full of oxygen and noise. They praise God that her crying does not stop until she finds the arms she knows as mother.

Our father and his son-in-law are in the kitchen preparing the shears. They sharpen them against a stone cube and like flint sometimes a spark appears and then evaporates. The new father comes from the kitchen holding the shears and the old man follows him. The new father reaches for the bundle in Connie’s arms, for their daughter, swaddled in pinks and whites and creams. Connie cries and thus her daughter cries. The old aunties praise God for this, too. The new father holds his first daughter, tender. His thumb and forefinger are clamped at either side of her face and her whole, new body rests in his hand this way. He is holding his daughter in one hand and the shears in the other. The old aunties have Connie. He snips, first at the back of her head, and the cheers startle the first daughter to a scream. More cheer. He is working his way around her head, the crown and nape and behind her ears, snipping her hair onto the carpeted floor below. A kind relative collects it. When he has finished, the new father swivels her chin and body towards the audience and presents his newly piebald daughter. And the new father screams, TAKBEER! And they cheer, ALLAHU AKBAR! And the new father screams, TAKBEER! And they cheer, ALLAHU AKBAR! The new father screams, TAKBEER! And every soul that bore witness to the miracle of this first daughter testifies, ALLAHU AKBAR!

IV.

Here is your first birthday wish, first niece: You are a first daughter and I am a first daughter, so we must hold on to the rope of it. And hold fast to the rope of Allah, and be not divided among yourselves. May there never be another day I compare you to the daughter I never got. Bright eyes always and an insatiable laugh. I couldn’t say your name, even after I knew your weight in my arms. Even when your mother and I sat down for a meal as something long lost. Even as we tried to start over and she placed you in my care, I had to search myself for a good feeling. Subhanallah. I missed her wedding and I missed your aqiqah, but hold fast to the rope. With your molars. First niece, learn the names of things. Know that this was jealousy and rage and selfishness. I had to bury a bodiless daughter. And then I buried the altar I built for her. The very tiny idea of her. Her name I keep to myself. The life I conjured for her. Her little soulless soul. Your mother had what I cannot have and now I face you. Your mother had what I cannot have but don’t excuse me. Don’t even forgive me. Hold fast to the slippery thread that binds us—first daughters born to young mothers. Be patient with me but hold me responsible. Make me look you in the eye. Demand my friendship. Steal from my bookshelves. Tell me the secret things you cannot bring to your mother. Know that an aunt is an anchor you can come back to. The birthday wish, first niece: Never let go the binding rope. Never sip from the gourd of dry rage. Never let anyone called friend or stranger—or even sister—cross your path with intentions to shoulder your springtime or bloom.